On a late afternoon about 20 years ago, I stepped into a slow elevator with my college’s most productive, famous, and taciturn senior professor. After 10 seconds of silence, I asked, “Did you publish anything yet today?” He stared at me for about 4 seconds and said, “The day’s not over.” Cool . . . very Clint Eastwood-like. Most of us have some super-productive days and we have some bad days, but most lie in-between. If we could figure out what leads to great days, we might be able to trigger more of them in our life. For instance, if you want to write a whole lot, there might be a way to set up your day so that this happens with a surprising amount of ease. Think of the most recent “great day” you had. What made it great, and how did it start? For about 20 years, every time somebody told me they had a great day, I’d ask “What made it great? How did it start out? About 50% of the time its greatness had to do with an external “good news” event like something great happening at work, great news from their kids or spouse, a nice surprise, or nice call or email from a grateful person or an old friend. The other 50% of the time, the reason for “greatness” was more “internal.” They had a super productive day, they finished a project or a bunch of errands, or they had a breakthrough solution to a problem or something they should do. External successes are easy to celebrate with our friends. Internal successes are more unpredictable. What made today a great day and what sabotaged yesterday? When people had great days, one reoccurring feature was that they started off great. There was no delay between when they got out of bed and when they Unleashed the Greatness. People said things like, “I just got started and seemed to get everything done,” or “I finished up this one thing and then just kept going.” One of the most productive authors I've known said that got up six days a week at 6:30 and wrote from 7:00 to 9:00 without interruption. Then he kissed his wife good-bye and drove into school and worked there. When I asked how long he had done that he said, “Forever.” About a year ago, I started toying with the idea that "Your first two hours set the tone for the whole day." Think of your last mediocre day. Did it start out mediocre? That would also be consistent with this notion. We can’t trigger every day to be great, but maybe we have more control than we think. If we focus on making our first two hours great, it might set the tone for the rest of the day. What we need to decide is what we can we do in those first two hours after waking that would trigger an amazing day and what would sabotage it and make it mediocre. For me, it seems writing, exercise, prayer, or meditation are the good triggers, and it seems answering emails, reading the news, or surfing are the saboteurs. Here’s to you having lots of amazing days. One’s where you can channel your best Clint Eastwood impression and say, “The day’s not over.”  In 2018, six of my research articles in JAMA-related journals were retracted. These retractions offer some useful lessons to scholars, and they also offer some useful next steps to those who want to publish eating behavior research in medical journals or in the social sciences. These six different papers offer some topic-related roadmaps that could be useful. First, they were originally of interest to journals in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) network, and they would probably be of interest to other journals in medicine, behavioral economics, marketing, nutrition, psychology, health, and consumer behavior. Second, they each show what a finished paper might look like. They show the positioning, relevant background research, methodological approach, and relevance to clinical practice or to everyday life. I think all of these topics are interesting and have every-day importance. This document provides a two-page template for each one that shows 1) An overview why it was done, 2) the abstract (or a summary if there was no abstract), 3) the reason it was retracted, 4) how it could be done differently, and 5) promising new research opportunities on the topic. Making specific hypotheses and testing them followed by open science principles will be the best next way forward on these topics.[1] Academia can be a tremendously rewarding career both you and for the people who benefit from you research. Best wishes in moving topics like these forward, and best wishes on a great career. [1] A useful description of these principles can be found at Klein, O., Hardwicke, T. E., Aust, F., Breuer, J., Danielsson, H., Hofelich Mohr, Al, …. Frank, M. C. (2018). A Practical guide for transparency in psychological science. Collabra: Psychology, 4 (1), 20.

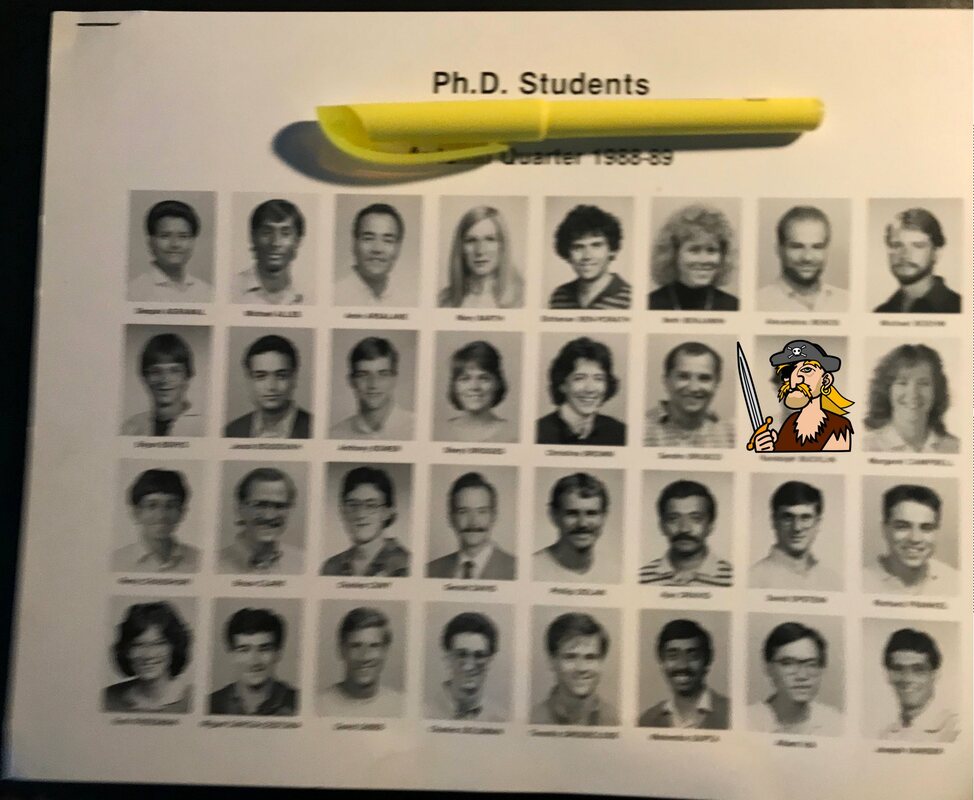

(This is an edited version of the "Shirking or Working from Home" blog I wrote as the Executive Director of Research for VitalSmarts).  Working from home is one of the 5,000 great benefits of being an academic. But it can also turn into too much of a good thing. Before the coronavirus, a lot of schools were hesitant to let staff work from home. “Working from home” rhymes too closely with “Shirking from home.” It includes surfing, posting, grazing, running errands, crushing Candy Crush, calling your brother “just because,” rereading online stories about the coronavirus, updating your vita, and spacing out on conference calls. But what if working from home looked different? What if working from home made you 13% more productive, made you feel more satisfied with your job, and made you half as likely to send your vita off to another school? This is in line with what was found in a 2015 Stanford study of a large Chinese travel firm called CTrip. Researchers randomly split 249 call center employees from Shanghai into two groups. For nine months, half of them kept working at their desks as usual, and the other half were told to work from home four days a week (one day a week they came into the office). Then the researchers measured everything from the number of calls they made, to job satisfaction, to breaks taken, to sick days… everything but Facebook Likes and Candy Crush scores. One conclusion: Working from home can make people more productive. But wait. Before you move all of your books back home, there’s a huge caveat from this study (aside from country, culture, and industry): These workers had very specific measures of productivity—phone calls per minute and the amount of time spent on the phone. Since working at home requires a discipline muscle that many of us need to strengthen, it’s easy to let our first days or weeks at home be structured by meetings and not our mission. That is, we might view the phone or web meetings on our calendar as the “Big rocks” of our day instead of seeing our biggest projects as our biggest rocks. After you conduct a weekly review of the projects that are most pressing, these suggestions might help. • Identify the three biggest project tasks you need to complete each day (not including meetings). • Make a promise to complete these tasks and deliver results to another person (boss or coworker). • Check in for a follow-up after making the delivery. This is the productivity side of working at home. But there’s another side to working at home that has been widely ignored. It’s the human side. There’s a story of three people who find themselves stranded on an uncharted desert island. Sort of like Gilligan’s Island, but without commercials. After years of learning how to smoothly work together to survive, the trio one day finds a bottle with a genie in it. The genie grants each person a wish. The first wishes to be back home in California, and—poof—she’s gone. The second wishes to be reunited with his family in Texas, and—poof—he’s gone. The third person looks around the empty island and says to the genie, “You know, I miss my two friends. I wish they were back.” Here’s the rest of the story about the Chinese workers. After nine months of working at home, the study was over. The workers were told they could continue working from home four days a week or they could come back and grind it out in-office for the full five. Slightly more than half of these workers wanted to come back and work in the office. They reported they were too “lonely.” There’s a human side to working at home. We can use our VitalSmarts tools to strengthen our communication muscle and our productivity muscle, but we might still feel like something is missing. Leaning in (versus spacing out) during meetings might help, and checking in or following up after finishing a project piece might help. But this human solution will need some personal thought and personal tailoring for each of us. If we’re feeling restless after 4 days at home, the human side is where we might want to look. And maybe call your brother “just because.”  If you’re a PhD student, you are in great company. But "being in great company" has a very special meaning that's important not to overlook -- it means you are not alone. Your bumpy PhD experience is surprisingly universal across different schools and different programs. If you’re a PhD student in microbiology, you have more in common with a PhD student in history than someone in medical school. If you’re a PhD student in economics, you have more in common with a PhD student in physics than with an MBA student. Despite this universal experience, many, many PhD students feel very alone. They feel anxious about their uncertain future, anxious about their abilities, and anxious about a personal life that seems to be passing them by. Having been an informal confident to many PhD students in different majors or with different advisors, I’ve found that many of their real concerns are difficult for them to talk about. This further magnifies their feeling of isolation because they don’t realize how many other people have faced and often conquered a similar problem. There’s power in knowing someone else found a path out of the same woods you feel you’re in. For about 20 years I taught an interdisciplinary PhD course at the University of Illinois and then at Cornell. Aside from the academic objectives, one of my personal objectives of this course was to help students begin to conquer these anxieties. One way we tried to tackle this was by asking students if they wanted to volunteer to write a short description about a “friend” who was facing a troubling problem. Many weeks we would discuss one of these anonymously written “case studies” for 10-15 minutes during class.

Two good things happened almost every week. First, the 8-16 students in the class all realized that they weren’t alone in some of the problems they faced. Second, they heard a wide range of rational (non-emotional) solutions and perspectives to each problem they probably wouldn’t have heard from an officemate or a partner.

There are three examples of PhD Student Case Studies in the downloadable pdf, and they can be used in a number of different ways.

There’s power in knowing there are a lot of different ways a PhD student can get out of the woods. |

Welcome...Fun, useful, or wacky experiences about getting tenure, teaching better, publishing more, and having an incredibly rewarding career.

Categories

All

Some Blog ShortcutsArchives

September 2020

|

||||||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed