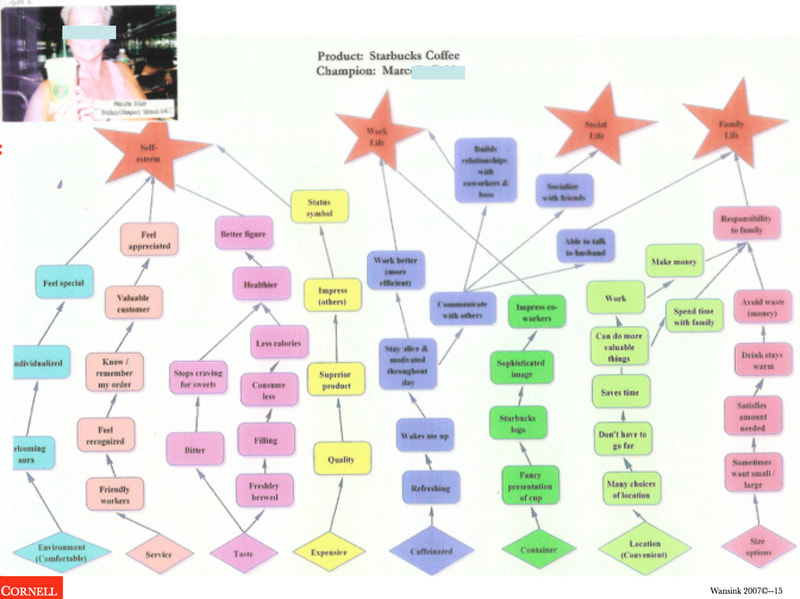

1. Laddering |

2. Prototyping |

3. Inside Sources

|

|

Laddering uncovers the secrets of brand champions . . . and how to best spread the word

|

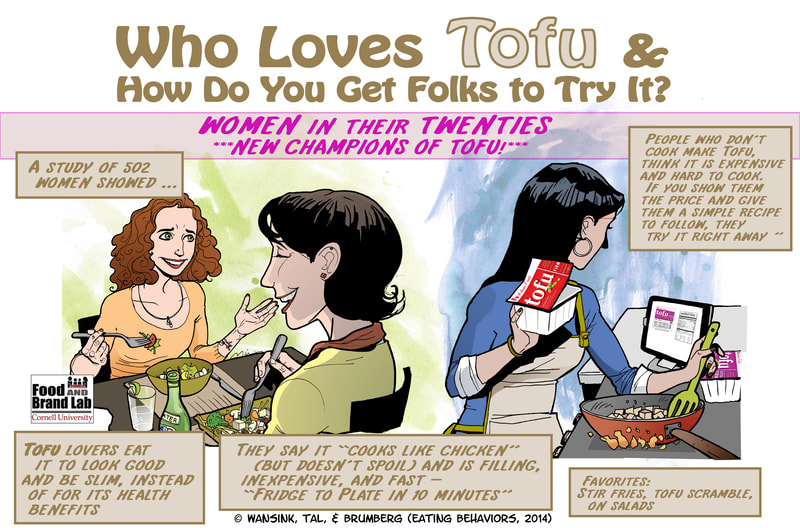

Prototyping Brand Champions will help you discover how to find the latent next wave of champions out there

|

Here's the perfect way to locate and leverage inside sources of brand champion insights

| ||||||||||||||||||

In most households, the decision of what to eat for breakfast, lunch, dinner, and snacks is determined by what foods the grocery shopper – the nutrition gatekeeper – purchases. The nutritional gatekeeper is the person who basically plans most of the meals – buying food and preparing it. Although they might not realize it, they have a big influence over what food ends up getting eaten both inside and outside the house.

Suppose a teenager wants to eat Pop-tarts, but there are not any in the house. The gatekeeper has de facto decided they won’t be on the menu. This poor Pop-tart hungry teenager would have to make a special trip to the grocery store, or to put pressure on Mom or Dad to put them at the top of the next shopping list.[i]

Exactly how much influence does a gatekeeper have?

On a steamy Manilla-like August day in Washington DC, I met with 800 dieticians and nurses at the American Associations of Diabetes Educators. These people are paid to know how people shouldeat and how they doeat. They watch people – and their families – eat day in and day out. I asked them about the Nutritional Gatekeeper, the person who does most the shopping and cooking in a household (92% of the time this is the same person). I asked them to estimate what percentage of the food eaten by their family – snacks, meals, out-of-the-house meals, everything – did they control. Their answer surprised me.

They estimated that the Gatekeeper controlled 72% of the food decisions of their children and spouse.[ii] After all, they were the one who bought everything that was eaten at home, they are the one who either made their children’s lunches or gave them enough money to afford whatever lunch or snack they wanted, and they were the ones who can nudge the restaurant orders of their family by what they recommend or order themselves.

We have asked lots of people to estimate this percentage. Some are 10 points lower or 10 points higher, but its always in this range. There is always one group of people whose estimates are always the highest. These are people who also rate themselves as good cooks. This made some sense. It was in line with a study we did that showed that many veggie lovers[iii]claimed to either be a good cook, live with a good cook, or to have had a parent who was a good cook.[iv] What was not clear was what these good cooks looked like and why they thought they were so influential.

We decided to see if we could track down the mysterious North American Good Cook and get some psychographic snapshots of them and the impact they have. To do this, we surveyed 453 “good cooks” who were considered “way above average” by at least one member of their family. They came from a wide range of ethnicities, income levels, and education levels. Besides being good cooks, the all had one thing in common – they had never attended culinary school. Some learned from a parent or on their own, some cooked out of necessity, and some for fun. We asked them 152 questions about how they cooked, what they cooked, when they cooked, what kind or person they were, what they did in their spare time. Almost everything. We found that although not all good cooks are created equal, 82% of them fit fairly neatly into one of five personality profiles. They could either be classified as Giving Cooks, Competitive Cooks, Healthy Cooks, Methodical Cooks, or Innovative Cooks.[vii]

Lessons from the Great Cook Next Door

All cooks influence their families more than they realize, but great cooks seem to be able to turn children into healthier eaters. What is a great cook look like? A study of 453 great cooks, showed that most of them tend to fall into one of five basic groups:[viii]

• Giving Cooks (22%). Friendly, well-liked, enthusiastic cooks who specialize on comfort foods for family gatherings and large parties. Giving cooks seldom experiment with new dishes, instead relying on traditional favorites. The only fault of the Giving Cook is they also tend to provide too many home-baked goodies for their family.

• Healthy Cooks (20%). Optimistic, book-loving, nature enthusiasts who are most likely to experiment with fish and with fresh ingredients, including herbs.

• Innovative Cooks (19%). The most creative, trend-setting of all cooks. They seldom us recipes, they experiment with ingredients, cuisine styles, and cooking methods.

• Methodical Cooks (18%).Often weekend hobbyists who are talented, but who rely heavily on recipes. Although somewhat inefficient in the kitchen, their creations always look exactly like the picture in the cookbook.

• Competitive Cooks (13%). The Iron Chef of the neighborhood. Competitive cooks are dominant personalities who cook in order to impress others. These are perfectionists who are intense in both their cooking and entertaining.

Do not fit into one of these categories? No worries. Find the cooking personality that best resembles you or that you most aspire to be. Then simply try to cook at home. The key is in your habits – your shopping habits, cooking habits, and eating habits. Learn that they do not sell toast in the grocery store. Learn the recipe for boiled water. Then simply give your children a wide varied diet and reasonable serving sizes. The food does not have to be great – just varied and reasonably sized.

All of these cooks – except one – appeared to help their family eat healthier. They all did this largely through the variety of food they served. Serving a wide variety of food can make eating pleasurable and can lead their children and spouse to enjoy a wide range of foods other than the standard, fatty, salty, sweet ones for which we have a natural hankering.

Which great cook seemed to have the least positive impact on adult eating habits? Interestingly enough, it was the most common one – the Giving Cook – and they were also the most frequent baker and dessert maker. Although they still put the stamp of variety on their meals, it was in the form of carbohydrates instead of the form of vegetable-heavy cuisine.

Does this mean that if you are not a good cook that your children are destined to grow up eating dinners that consist of Dominos Pizza and Cheetos? No, of course not.

What it reinforces is that parents can influence the eating habits of their children in either a good way or a bad way. One key take-away for us “not so good cooks” is the good we cando just by adding more variety to our meals. How? These good cooks do it by 1) buying different foods, 2) making different recipes (including different ethnic foods), 3) substituting new ingredients into favorite recipes (mainly vegetables and spices), 4) taking kids to the grocery store and letting them choose a new, healthy food, 5) visit authentic ethnic restaurants. Relevant to the last point, McDonald’s is not a Scottish restaurant.

When a child develops a taste for a wide range of foods, healthy foods can be more easily substituted for the less healthy ones. The more he or she will develop a taste for something other than pizza, French fries, candy, and Juicy-Juice. They still may not learn to lovebroccoli, but they will be more willing to eat it occasionally for dinner or with a low calorie ranch dressing as a snack.[ix]

Yet part of whether your daughter will love broccoli or your son will love carrots will have been determined before you ever see them. Because this happens before they can talk, we often casually refer to it as “inherited.”

Endnotes and References

[i]For insights about the blending of responsibilities and tasks in the house, see Carol M. Devine, M. M. Connors, Jeffrey Sobal, and Carol Bisogni, “Sandwiching It In: Spillover of Work onto Food Choices and Family Roles in Low- and Moderate-Income Urban Households,” Social Science & Medicine(February 2003), 56:3, 617-63. David A. Levitsky, Craig A. Halbmaier, and Gordona Mrdjenovic, “The Freshman Weight Gain: A Model for the Study of the Epidemic of Obesity,” International Journal of Obesity(November 2004), 28:11, 1435-1442

[ii]Interestingly, we have repeated this with a lot of different people. Good cooks, non cooks, young parents, empty nesters, grandmothers, single moms. They vary a little bit, but all end up estimating right around 72%.

[iii]This study was showed this for vegetable-loving adults, but the focus of the research article was on soy, and that is all that is reported. Brian Wansink and Randall Westgren, “Profiling Taste-Motivated Segments,” Appetite(December (2003), 41:3, 323-327.

[iv]Brian Wansink and JaeHak Cheong, “Taste Profiles That Correlate with Soy Consumption in Developing Countries,” Pakistan Journal of Nutrition(December 2002), vol. 1, no. 6, pp. 276-278. Brian Wansink and Randall Westgren, “Profiling Taste-Motivated Segments,” Appetite(December 2003), 41:3, 323-327.

[v]Brian Wansink and Keong-mi Lee, “Cooking Habits Provide a Key to 5 a Day Success,” Journal of the American Dietetic Association(November 2004), 104:11, 1648-1650.

[vi]Brian Wansink, Ganaël Bascoul, and Gary T. Chen, “The Sweet Tooth Hypothesis: How Fruit Consumption Relates to Snack Consumption, Appetite(2006), forthcoming.

[vii]The first Nutritional Gatekeeper study on this was published in Food Quality and Preference, but they never wanted us to focus on methodology and not percentages. The percentages we were able to then put into the book, Marketing Nutrition in 2004. The full references: Brian Wansink, “Profiling Nutritional Gatekeepers: Three Methods for Differentiating Influential Cooks,” Food Quality and Preference(June 2003), 14:4, 289-297, and Brian Wansink, Marketing Nutrition: Soy, Functional Foods, Biotechnology, and Obesity, (Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 2005).

[viii]See Brian Wansink, “Profiling Nutritional Gatekeepers: Three Methods for Differentiating Influential Cooks,” Food Quality and Preference(June 2003), 14:4, 289-297.

[ix]Picky eater at home? Take heart. Gentle persistence will be rewarded. One taste does not change a person. Professor LeAnn Birch has shown that this can take up to 15 one-bite attempts, but most children end up eventually coming around to liking more than just French fries, ice cream, and Jell-o.

[x]This longitudinal study involves control groups, panel diaries, and reliability checks, all which are too boring for a sidebar. Also, it is important to avoid foods that could cause choking, such as popcorn, nuts, potato chips, whole kernel corn, berries, grapes, hot dogs, raw vegetables, raisins, dry flake cereals. To keep abreast on the findings from this panel study, stay tuned to www.FoodPsychology.com.

Suppose a teenager wants to eat Pop-tarts, but there are not any in the house. The gatekeeper has de facto decided they won’t be on the menu. This poor Pop-tart hungry teenager would have to make a special trip to the grocery store, or to put pressure on Mom or Dad to put them at the top of the next shopping list.[i]

Exactly how much influence does a gatekeeper have?

On a steamy Manilla-like August day in Washington DC, I met with 800 dieticians and nurses at the American Associations of Diabetes Educators. These people are paid to know how people shouldeat and how they doeat. They watch people – and their families – eat day in and day out. I asked them about the Nutritional Gatekeeper, the person who does most the shopping and cooking in a household (92% of the time this is the same person). I asked them to estimate what percentage of the food eaten by their family – snacks, meals, out-of-the-house meals, everything – did they control. Their answer surprised me.

They estimated that the Gatekeeper controlled 72% of the food decisions of their children and spouse.[ii] After all, they were the one who bought everything that was eaten at home, they are the one who either made their children’s lunches or gave them enough money to afford whatever lunch or snack they wanted, and they were the ones who can nudge the restaurant orders of their family by what they recommend or order themselves.

We have asked lots of people to estimate this percentage. Some are 10 points lower or 10 points higher, but its always in this range. There is always one group of people whose estimates are always the highest. These are people who also rate themselves as good cooks. This made some sense. It was in line with a study we did that showed that many veggie lovers[iii]claimed to either be a good cook, live with a good cook, or to have had a parent who was a good cook.[iv] What was not clear was what these good cooks looked like and why they thought they were so influential.

We decided to see if we could track down the mysterious North American Good Cook and get some psychographic snapshots of them and the impact they have. To do this, we surveyed 453 “good cooks” who were considered “way above average” by at least one member of their family. They came from a wide range of ethnicities, income levels, and education levels. Besides being good cooks, the all had one thing in common – they had never attended culinary school. Some learned from a parent or on their own, some cooked out of necessity, and some for fun. We asked them 152 questions about how they cooked, what they cooked, when they cooked, what kind or person they were, what they did in their spare time. Almost everything. We found that although not all good cooks are created equal, 82% of them fit fairly neatly into one of five personality profiles. They could either be classified as Giving Cooks, Competitive Cooks, Healthy Cooks, Methodical Cooks, or Innovative Cooks.[vii]

Lessons from the Great Cook Next Door

All cooks influence their families more than they realize, but great cooks seem to be able to turn children into healthier eaters. What is a great cook look like? A study of 453 great cooks, showed that most of them tend to fall into one of five basic groups:[viii]

• Giving Cooks (22%). Friendly, well-liked, enthusiastic cooks who specialize on comfort foods for family gatherings and large parties. Giving cooks seldom experiment with new dishes, instead relying on traditional favorites. The only fault of the Giving Cook is they also tend to provide too many home-baked goodies for their family.

• Healthy Cooks (20%). Optimistic, book-loving, nature enthusiasts who are most likely to experiment with fish and with fresh ingredients, including herbs.

• Innovative Cooks (19%). The most creative, trend-setting of all cooks. They seldom us recipes, they experiment with ingredients, cuisine styles, and cooking methods.

• Methodical Cooks (18%).Often weekend hobbyists who are talented, but who rely heavily on recipes. Although somewhat inefficient in the kitchen, their creations always look exactly like the picture in the cookbook.

• Competitive Cooks (13%). The Iron Chef of the neighborhood. Competitive cooks are dominant personalities who cook in order to impress others. These are perfectionists who are intense in both their cooking and entertaining.

Do not fit into one of these categories? No worries. Find the cooking personality that best resembles you or that you most aspire to be. Then simply try to cook at home. The key is in your habits – your shopping habits, cooking habits, and eating habits. Learn that they do not sell toast in the grocery store. Learn the recipe for boiled water. Then simply give your children a wide varied diet and reasonable serving sizes. The food does not have to be great – just varied and reasonably sized.

All of these cooks – except one – appeared to help their family eat healthier. They all did this largely through the variety of food they served. Serving a wide variety of food can make eating pleasurable and can lead their children and spouse to enjoy a wide range of foods other than the standard, fatty, salty, sweet ones for which we have a natural hankering.

Which great cook seemed to have the least positive impact on adult eating habits? Interestingly enough, it was the most common one – the Giving Cook – and they were also the most frequent baker and dessert maker. Although they still put the stamp of variety on their meals, it was in the form of carbohydrates instead of the form of vegetable-heavy cuisine.

Does this mean that if you are not a good cook that your children are destined to grow up eating dinners that consist of Dominos Pizza and Cheetos? No, of course not.

What it reinforces is that parents can influence the eating habits of their children in either a good way or a bad way. One key take-away for us “not so good cooks” is the good we cando just by adding more variety to our meals. How? These good cooks do it by 1) buying different foods, 2) making different recipes (including different ethnic foods), 3) substituting new ingredients into favorite recipes (mainly vegetables and spices), 4) taking kids to the grocery store and letting them choose a new, healthy food, 5) visit authentic ethnic restaurants. Relevant to the last point, McDonald’s is not a Scottish restaurant.

When a child develops a taste for a wide range of foods, healthy foods can be more easily substituted for the less healthy ones. The more he or she will develop a taste for something other than pizza, French fries, candy, and Juicy-Juice. They still may not learn to lovebroccoli, but they will be more willing to eat it occasionally for dinner or with a low calorie ranch dressing as a snack.[ix]

Yet part of whether your daughter will love broccoli or your son will love carrots will have been determined before you ever see them. Because this happens before they can talk, we often casually refer to it as “inherited.”

Endnotes and References

[i]For insights about the blending of responsibilities and tasks in the house, see Carol M. Devine, M. M. Connors, Jeffrey Sobal, and Carol Bisogni, “Sandwiching It In: Spillover of Work onto Food Choices and Family Roles in Low- and Moderate-Income Urban Households,” Social Science & Medicine(February 2003), 56:3, 617-63. David A. Levitsky, Craig A. Halbmaier, and Gordona Mrdjenovic, “The Freshman Weight Gain: A Model for the Study of the Epidemic of Obesity,” International Journal of Obesity(November 2004), 28:11, 1435-1442

[ii]Interestingly, we have repeated this with a lot of different people. Good cooks, non cooks, young parents, empty nesters, grandmothers, single moms. They vary a little bit, but all end up estimating right around 72%.

[iii]This study was showed this for vegetable-loving adults, but the focus of the research article was on soy, and that is all that is reported. Brian Wansink and Randall Westgren, “Profiling Taste-Motivated Segments,” Appetite(December (2003), 41:3, 323-327.

[iv]Brian Wansink and JaeHak Cheong, “Taste Profiles That Correlate with Soy Consumption in Developing Countries,” Pakistan Journal of Nutrition(December 2002), vol. 1, no. 6, pp. 276-278. Brian Wansink and Randall Westgren, “Profiling Taste-Motivated Segments,” Appetite(December 2003), 41:3, 323-327.

[v]Brian Wansink and Keong-mi Lee, “Cooking Habits Provide a Key to 5 a Day Success,” Journal of the American Dietetic Association(November 2004), 104:11, 1648-1650.

[vi]Brian Wansink, Ganaël Bascoul, and Gary T. Chen, “The Sweet Tooth Hypothesis: How Fruit Consumption Relates to Snack Consumption, Appetite(2006), forthcoming.

[vii]The first Nutritional Gatekeeper study on this was published in Food Quality and Preference, but they never wanted us to focus on methodology and not percentages. The percentages we were able to then put into the book, Marketing Nutrition in 2004. The full references: Brian Wansink, “Profiling Nutritional Gatekeepers: Three Methods for Differentiating Influential Cooks,” Food Quality and Preference(June 2003), 14:4, 289-297, and Brian Wansink, Marketing Nutrition: Soy, Functional Foods, Biotechnology, and Obesity, (Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 2005).

[viii]See Brian Wansink, “Profiling Nutritional Gatekeepers: Three Methods for Differentiating Influential Cooks,” Food Quality and Preference(June 2003), 14:4, 289-297.

[ix]Picky eater at home? Take heart. Gentle persistence will be rewarded. One taste does not change a person. Professor LeAnn Birch has shown that this can take up to 15 one-bite attempts, but most children end up eventually coming around to liking more than just French fries, ice cream, and Jell-o.

[x]This longitudinal study involves control groups, panel diaries, and reliability checks, all which are too boring for a sidebar. Also, it is important to avoid foods that could cause choking, such as popcorn, nuts, potato chips, whole kernel corn, berries, grapes, hot dogs, raw vegetables, raisins, dry flake cereals. To keep abreast on the findings from this panel study, stay tuned to www.FoodPsychology.com.