"The best diet is the one you don't know you're on"

-- Mindless Eating

There are a lot of small changes you can make to your home that can help you eat better, lose weight, and enjoy food even more.

Keep heart. You don't have to go on a drastic diet, or hire a personal trainer. You can start off simple.

Keep heart. You don't have to go on a drastic diet, or hire a personal trainer. You can start off simple.

|

Here's why we overeat . . .

|

. . . and some quick ways to stop it

|

Mindless Eating SolutionsThere's no magic pill to help you eat better. Fortunately there's another solution.

|

Let Your Kitchen Make You Healthier by Design |

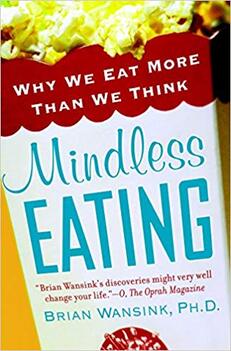

Your First ToolStart with this 10-point Scorecard. It tells whether your kitchen is making you fit or fat . . . and what you can do to change it tonight.

| ||||||

Mindless Eating: Why We Eat More Than We Think

|

Did you ever eat the last piece of crusty, dried-out chocolate cake even though it tasted like chocolate-scented cardboard? Ever finish eating a bag of French fries even though they were cold, limp, and soggy? It hurts to answer questions like these.

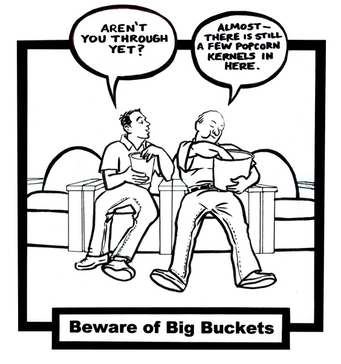

Why can we overeat food that does not even taste good? We overeat because there are signals and cues around us that tell us to eat. It is simply not in our nature to pause after every bite and contemplate whether we are full. As we eat, we unknowingly – mindlessly – look for signals or cues that we have had enough. For instance, if there is nothing remaining on the table – that is a cue that its time to stop. If everyone else has left the table, turned off the lights, and we are sitting alone in the dark – that is another cue. For many of us, as long as there are still a few milk-soaked Fruit Loops left in the bottom of the cereal bowl, there is still work to be done. It does not matter if we are full, and it does not matter if we do not even really like Fruit Loops. We eat as if it is our mission to finish them. [i] |

|

We Overeat When We're Not Hungry Because of the Cues Around Us

Take movie popcorn, for instance, There is no “right amount” of popcorn to eat during a movie. There are no rules-of-thumb or FDA guidelines. People eat however much they want depending on how hungry they are and how good it tastes. At least that is what they say.

My graduate students and I think different. We think that the cues around us – like the size of a popcorn bucket – can provide subtle but powerful suggestions about how much one should eat. These cues might even short-circuit a person’s hunger and taste; they might lead them to eat even if they are not hungry and even if the food does not taste very good.

My graduate students and I think different. We think that the cues around us – like the size of a popcorn bucket – can provide subtle but powerful suggestions about how much one should eat. These cues might even short-circuit a person’s hunger and taste; they might lead them to eat even if they are not hungry and even if the food does not taste very good.

If you were living in Chicago a few years back, you might have been our guest at a suburban theatre matinee. If you lined up to see the 1:30 PM Saturday showing of Mel Gibson’s new action movie called Payback, you would have had a surprise waiting for you: a free bucket of popcorn.

Every person who bought a ticket – even though many of them had just eaten lunch – was given a soft drink and either a medium-size bucket of popcorn or a large-size, bigger-than-your-head bucket of popcorn. They were told that the popcorn and soft drinks were free and that we hoped they would be willing to answer a few concession stand-related questions after the movie.

There was only one catch. This wasn’t fresh popcorn. Unknown to the movie goers and to even my graduate students, this popcorn had been popped 5 days earlier, and had been left sitting out so that it was stale enough to squeek when it was eaten.

Every person who bought a ticket – even though many of them had just eaten lunch – was given a soft drink and either a medium-size bucket of popcorn or a large-size, bigger-than-your-head bucket of popcorn. They were told that the popcorn and soft drinks were free and that we hoped they would be willing to answer a few concession stand-related questions after the movie.

There was only one catch. This wasn’t fresh popcorn. Unknown to the movie goers and to even my graduate students, this popcorn had been popped 5 days earlier, and had been left sitting out so that it was stale enough to squeek when it was eaten.

|

To make sure it was kept separate from the rest of the theatre popcorn, it was transported to the theatre in bright yellow garbage bags. It was the color yellow that screams “Biohazard.” The popcorn was clean and safe to eat, but it was so stale that at least two moviegoers said it was like eating Styrofoam packing peanuts. Two others, forgetting they had been given it for free, even asked for their money back. During the movie some people eating this stale popcorn would eat a couple bites, put the bucket down, pick it up in a few minutes later and have a few more bites, put it down, and continue. It might not have been good enough to eat all at once, but they did not seem able to leave it alone.

Both popcorn containers – medium and large – had been selected to be big enough that nobody would finish all of the popcorn. And each person was given his or her own individual popcorn bucket so there would be no sharing. As soon as the movie ended and the credits began to roll, we asked everyone to take their popcorn with them. When the movie was over we gave them a half-page survey (on bright biohazard-colored yellow paper) that asked them whether they agreed to statements like “I ate too much popcorn, ” by circling a number from 1 (strongly disagree) to 9 (strongly agree). As they did this, we weighed their remaining popcorn. When the people who had been given the large buckets handed their left-over popcorn to us, we said, “Some people tonight were given medium-size buckets of popcorn and others, like yourself, were given these large-size buckets. We have found that the average person who is given a large-size bucket of popcorn eats about 53% more popcorn than if they are given a medium-size bucket. Do you think you ate more because you had the given a large-size?” Most disagreed. Many smugly said, “That wouldn’t happen to me,” “Things like that don’t trick me,” “I’m pretty good at knowing when I’m full.” |

That may be what they believed, but it is not what happened.

If somebody was eating stale, 5-day-old popcorn, you might think they would take a handful or two, cough, grimace, and stop eating. That did not happen. These people still ate more an average of 173 calories of popcorn. This is a lot more than a handful. In fact, this is roughly the equivalent of 21 handfuls of popcorn. Clearly the quality of food is not what led them to eat. Once these moviegoers started in on their bucket, the taste of the popcorn did not matter.[ii] Even though they had possibly just eaten lunch, people who were given big buckets of stale popcorn ate 53% more than those given medium-size buckets. Give them a lot, and they eat a lot.

And this was 5-day-old, stale popcorn!

We have run other popcorn studies, and the results were always the same. Each time we ran it, we tweeked in it different ways. We ran it in different theatres, in different states, and in different types of movies. It did not matter if these moviegoers were in Pennsylvania, Illinois, or Iowa, all of our popcorn studies led to the same conclusion. People eat more when you give them a bigger container. Period. It does not matter whether the popcorn is good or bad, or whether they were hungry or full when they sat down for the movie.

If somebody was eating stale, 5-day-old popcorn, you might think they would take a handful or two, cough, grimace, and stop eating. That did not happen. These people still ate more an average of 173 calories of popcorn. This is a lot more than a handful. In fact, this is roughly the equivalent of 21 handfuls of popcorn. Clearly the quality of food is not what led them to eat. Once these moviegoers started in on their bucket, the taste of the popcorn did not matter.[ii] Even though they had possibly just eaten lunch, people who were given big buckets of stale popcorn ate 53% more than those given medium-size buckets. Give them a lot, and they eat a lot.

And this was 5-day-old, stale popcorn!

We have run other popcorn studies, and the results were always the same. Each time we ran it, we tweeked in it different ways. We ran it in different theatres, in different states, and in different types of movies. It did not matter if these moviegoers were in Pennsylvania, Illinois, or Iowa, all of our popcorn studies led to the same conclusion. People eat more when you give them a bigger container. Period. It does not matter whether the popcorn is good or bad, or whether they were hungry or full when they sat down for the movie.

|

Did people eat because they liked the popcorn? No. Did they eat because they were hungry? No. They ate because of all the cues around them – not only the size of the popcorn bucket – but also other factors I will discuss later, such as the distracting movie, the sound of people eating popcorn around them, and the eating scripts we take to movie theatres with us.[iii] All of these were cues that signaled that it was okay to keep on eating and eating.[iv]

Does this mean we can avoid mindless eating simply by replacing large bowls with smaller bowls? That is a small piece of the puzzle, but there are a lot more cues that can be engineered out of our lives. As you will see, these hidden persuaders can even take the form of a tasty description on a menu or a classy name on a wine bottle. Simply thinking that a meal will taste good can lead you to eat more. You will not even know it happened. |

We Don't Really Know What Foods We Like and Don't Like -- Our Taste is Subjective

As Fine as North Dakota Wine.

There is a restaurant that is only open 15-20 nights a year and serves an inclusive prix-fixe theme dinner each night. A nice meal will cost you around $22, but to have it you will have to phone for reservations, and be seated at either 5:30 and 7:00 sharp. Despite these drawbacks, there is often a waiting list . . .

|

Welcome to The Spice Box.[v] The Spice Box looks like a restaurant; it sounds like a restaurant; and it smells like a restaurant. To the people eating there, it is a restaurant. To the people working there, it is a fine dining lab sponsored by the Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The Spice Box is a lab where both professional chefs and culinary hopefuls learn whether a new recipe will fly or go down in flames. It is a lab where waitstaff discover whether a new approach will sizzle or fizzle. It is also a lab where consumer psychologists figure out what makes a person nibble a little or inhale it all.

There is a secret and imaginary line down the middle of the dining room in The Spice Box. On one Thursday, diners on the left side of the room might be getting a different version of the shrimp coconut jambalaya entrée than those on the right. On the next Thursday, diners on the left side will be given a menu with basic English names for the food while those on the right will be given a menu with French-sounding names. On the Thursday after that, diners on the left side will hear each entrée described by a waiter while those on the right will read the same descriptions off the menu. At the end of the meal, sometimes we ask them some short survey questions, but other times we will instead carefully weigh how much food our guests have left on their plates. That way we do not have to rely on what they say, we can rely on what they do – which version of shrimp coconut jambalaya were they most likely to polish off.[vi]. |

But on one dark Thursday in the first week of a snow-covered February night in 2004 something a little more mischievous is being planned for those diners who braved the snow to keep their reservations. They are getting a full glass of Cabernet Sauvignon before their meal. Totally free. Compliments of the house.

This cabernet is not a fine vintage. In fact, it is a $2.00 bottle sold under the brand name “Charles Shaw” – popularly known as “Two Buck Chuck.” But the 41 diners given Two Buck Chuck do not know this. In fact, all the Charles Shaw labels have been soaked off the bottles, and they have been replaced with professionally-designed labels that are 100% fake.

Those on the left side of the room are being offered wine from the fictional Noah’s Winery, a new California label. The winery’s classic, italicized logo is enveloped by a simple graphic of grapes and vines. Below this, the wine proudly announces that it is “NEW from California.” After the diners arrive and are seated, the waiter or waitress says, “Good evening and welcome to The Spice Box. As you are deciding what you want to eat this evening, we are offering you a complimentary glass of Cabernet Sauvignon. It is from a new California winery called Noah’s Winery.” Each person was then poured a standard 3.8-oz glass of wine.[vii]

About an hour later, after they had finished their meal and were paying for it, we weighed the amount of wine left in each glass and the amount of the entrée left on each plate. We also had a record of when each diner had started eating and when they paid their bill and left.

This cabernet is not a fine vintage. In fact, it is a $2.00 bottle sold under the brand name “Charles Shaw” – popularly known as “Two Buck Chuck.” But the 41 diners given Two Buck Chuck do not know this. In fact, all the Charles Shaw labels have been soaked off the bottles, and they have been replaced with professionally-designed labels that are 100% fake.

Those on the left side of the room are being offered wine from the fictional Noah’s Winery, a new California label. The winery’s classic, italicized logo is enveloped by a simple graphic of grapes and vines. Below this, the wine proudly announces that it is “NEW from California.” After the diners arrive and are seated, the waiter or waitress says, “Good evening and welcome to The Spice Box. As you are deciding what you want to eat this evening, we are offering you a complimentary glass of Cabernet Sauvignon. It is from a new California winery called Noah’s Winery.” Each person was then poured a standard 3.8-oz glass of wine.[vii]

About an hour later, after they had finished their meal and were paying for it, we weighed the amount of wine left in each glass and the amount of the entrée left on each plate. We also had a record of when each diner had started eating and when they paid their bill and left.

|

That evening, diners on the right side of the room had exactly the same dining experience – with one exception. The waiter or waitress’s carefully scripted welcome introduced a cabernet “from a new North Dakota winery called Noah’s Winery.” The label was identical to that on the first bottle, except for the words “NEW from North Dakota.”

There is no Bordeaux region in North Dakota, nor is there a Burgundy region, nor a Champagne region. There is, however, a Fargo region, a Bismarck region, and a Minot region. It is just that there are no wine grapes grown in any one of them. California equals wine. North Dakota equals snow or buffalo. People who were given North Dakota wine believed it was North Dakota wine. But since it was the same wine as those who thought they were getting California wine, it should not influence their taste. Should it? It does. We knew from an earlier lab study that people who thought they were drinking North Dakota wine had such low expectations, that they rated the wine as tasting bad and their food as less tasty. If a California wine label can give a glowing halo to an entire meal, a North Dakota wine label casts a shadow onto everything it touches. But our focus this particular night was whether these labels would influence how much our diners ate. After the meals were over, the first thing we discovered was that both groups of people drank about the same amount of wine – all of it. This was not so surprising. It was only one glass of wine and it was a cold night. Where they differed was in how much food they ate and how long they lingered at their table. Compared to those unlucky dinners given wine with North Dakota labels, people who thought they had been given a free glass of California wine ate 11% more of their food – 19 of the 24 even cleaned their plates. They also lingered an average of 10 minutes longer at their table (64 minutes). They stayed pretty much until the wait staff starting dropping hints that the next seating would be starting soon. |

The night was not quite as magical for those given wine with the North Dakota labels. Not only did they leave more food on their plates, this probably was not much of a meal to remember because it went by so fast. North Dakota wine drinkers sat down, drank, ate, paid and were out in 55 minutes – less than an hour. For them, the dinner was clearly not a special meal, it was just food.

Exact same meals, exact same wine. Different labels, different reactions.

Now to a cold-eyed cynic, there should have been no difference between the two groups. They were given the exact same wine and same food. They should have eaten the same amount and enjoyed it the same.

They didn’t. They mindlessly ate. That is, once they were given a free glass of “California” wine they said to themselves: “This is going to be good.” Once they concluded it was going to be good, their experience lined up to confirm their expectations. They no longer had to stop and think about whether the food and wine were really as good as they thought. They had already decided.

Of course, the same thing happened to the diners who were given the “North Dakota” wine. Once they saw the label, they set themselves up for disappointment. There was no halo; there was a shadow. And not only was the wine bad, the entire meal fell short.

After our studies are over, we almost always “debrief” people and tell them what the study was about and what results we expect.[viii] For instance, with our different wine studies, we might say, “We think the average person drinking what they think is North Dakota wine will like their meal less than those given the “California” wine.” We then ask the kicker: “Do you think you were influenced by the State’s name you saw on the label?” Almost all will give the exact same answer: “No, I wasn’t.”

Exact same meals, exact same wine. Different labels, different reactions.

Now to a cold-eyed cynic, there should have been no difference between the two groups. They were given the exact same wine and same food. They should have eaten the same amount and enjoyed it the same.

They didn’t. They mindlessly ate. That is, once they were given a free glass of “California” wine they said to themselves: “This is going to be good.” Once they concluded it was going to be good, their experience lined up to confirm their expectations. They no longer had to stop and think about whether the food and wine were really as good as they thought. They had already decided.

Of course, the same thing happened to the diners who were given the “North Dakota” wine. Once they saw the label, they set themselves up for disappointment. There was no halo; there was a shadow. And not only was the wine bad, the entire meal fell short.

After our studies are over, we almost always “debrief” people and tell them what the study was about and what results we expect.[viii] For instance, with our different wine studies, we might say, “We think the average person drinking what they think is North Dakota wine will like their meal less than those given the “California” wine.” We then ask the kicker: “Do you think you were influenced by the State’s name you saw on the label?” Almost all will give the exact same answer: “No, I wasn’t.”

|

In the thousands of debriefings we have done for hundreds of studies, nearly every person who was “tricked” by the words on a label, the size of a package, the lighting in a room, or the size of a plate said, “I was not influenced by that.” They might acknowledge that others could be “fooled,” but they do not think they are. That is what gives mindless eating so much power over us – we are not aware it is happening.

Take the concept of anchoring. It emphasizes that people are really suggestible when it comes to numbers. If you ask people if there are more or less than 50 calories in an apple, most will say more. When you ask them how many, the average person will say “56.” If you had instead asked them if there were more or less than 150 calories in an apple, most would say less. When you ask them how many, the average person would instead say, “122.” People unknowingly anchor on the number they first hear and they let that bias them. This happens everywhere and no-one is aware it is happening. Each of these people would deny they were influenced. |

A while back, I teamed up with two professor friends of mine – Steve Hoch and Bob Kent – to see if anchoring influences how much food we buy in grocery stores. We believed that grocery shoppers who saw numerical signs such as “Limit 12 per person” would buy much more than those who signs such as “No limit person.”[ix] To nail down the psychology behind this, we repeated this study in different forms, using different numbers, different promotions (like “2 for $2” versus “1 for $1), and in different supermarkets and convenience stores. By the time we finished, we knew why these signs worked, how much they worked, and how they fooled people.

After the research was completed and published in a top journal, another friend and I were in the checkout line at a grocery store, where I saw a sign advertising gum, “10 packs for $2.00.” I was eagerly counting out ten packages onto the convey belt, when my friend commented, “Didn’t you just publish a big research paper on that?”

We are all tricked by our environment. Even if we “know it” in our head, most of the time we have way too much on our mind to remember it and act on it. That is why it is easier to change our environment than our mind.

After the research was completed and published in a top journal, another friend and I were in the checkout line at a grocery store, where I saw a sign advertising gum, “10 packs for $2.00.” I was eagerly counting out ten packages onto the convey belt, when my friend commented, “Didn’t you just publish a big research paper on that?”

We are all tricked by our environment. Even if we “know it” in our head, most of the time we have way too much on our mind to remember it and act on it. That is why it is easier to change our environment than our mind.

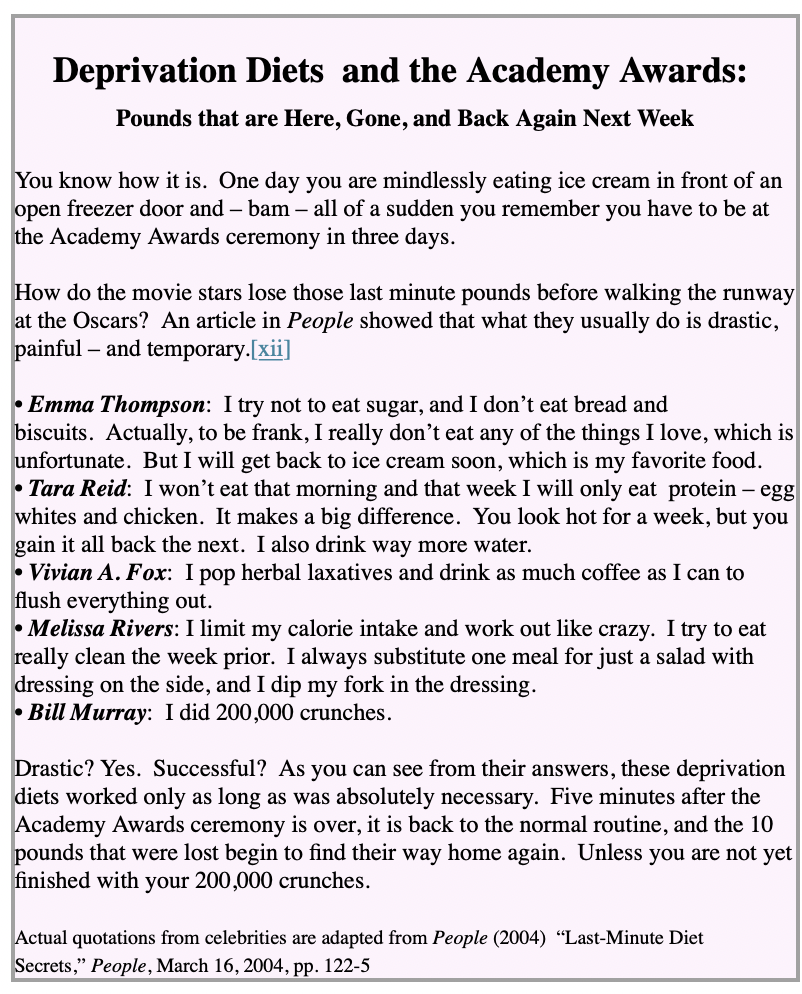

The Dieter's Dilemma We have all heard of somebody’s cousin’s sister who went on a huge diet before her high school reunion, lost tons of weight, kept it off, won the lottery, and lived happily ever after. Yet we also know about 95 times as many people who started a diet and gave up in discouragement, or who started a diet, lost weight, gained more weight, and then gave up in discouragement.[x] After that, they started a different diet and repeated the same depriving, discouraging, demoralizing process. Indeed, it is estimated that over 95% of all people who lose weight on a diet, gain it back.[xi]

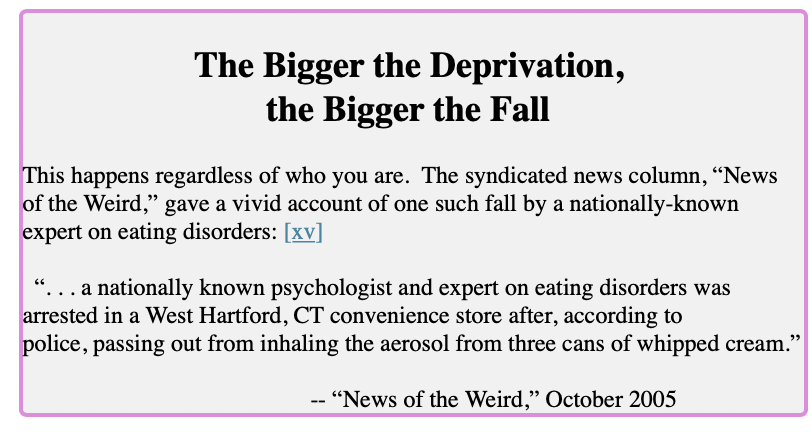

Most diets are deprivation diets. We deprive ourselves or deny ourselves of something – carbohydrates, fat, red meat, snacks, pizza, breakfast, chocolate, and so forth. Unfortunately, deprivation diets don’t work for three reasons: 1) Our body fights against them, 2) our brain fights against them, and 3) our day-to-day environment is booby-trapped with food. Millions of years of evolution have made our body too smart to fall for our little, “I’m-only-eating-salad,” trick. Our body’s metabolism is efficient. When it has plenty of food to burn, it turns the furnace up and burns up our fat reserves faster. When it has less food to burn, it turns down the furnace and burns it more slowly and efficiently. This efficiency helped our ancestors survive famines and barren winters. It does not help today’s deprived dieter. If you eat too little, the body goes into conservation mode and makes it even tougher to burn those pounds off. This type of weight loss is not mindless. It is like pushing a boulder up hill every second of every day. How much weight loss triggers the conservation switch? It seems that we can lose half a pound a week without triggering a metabolism slow-down.[xiii] Some people may be able to lose more, but everyone can lose at least half a pound a week and still be in full-burn mode. The only problem is that this is too slow for many people. Weight loss has to be all or nothing. This is why so many impatient people try to lose it all and end up losing nothing. Now for our brains. If we consciously deny ourselves something again and again, we are likely to end up craving it more and more.[xiv] It does not matter whether you are deprived of affection, vacation, television, or your favorite foods. Being deprived from anything you really like is not a great way to enjoy life. Nevertheless, the first thing many dieters do is cut out their comfort foods. This becomes a recipe for dieting disaster because any diet that is based on denying yourself the foods you really like is going to be really temporary. The foods we do not bite can come back to bite us. When the diet ends – either because of frustration or because of temporary success – you are back wolfing down these comfort foods with a hungry vengeance. With all that sacrificing you’ve been doing, there is a lot of catching up to do. |

When it comes to losing weight, we cannot rely only on our brain, or our “cognitive control,” A.K.A. willpower.[xvi] We make an estimated 248[xvii] food-related decisions each day, and it is almost impossible to have them all be text-book perfect. We have millions of years of evolution and instinct telling us to eat as often as we can and to eat as much as we can. Most of us simply do not have the mental fortitude to stare at a plate of warm cookies on the table and say, “I’m not going to eat a cookie, I’m not going to eat a cookie,” and then not eat the cookie. There is only so long before our “No, no, maybe, maybe” turns into a “Yes.”

Our bodies fight against deprivation, and our brains fight against deprivation.[xviii] And to make matters worse, our day-to-day environment is set-up to booby-trap any half-hearted effort we can muster up. There are great smells on every fast food corner. There are warm, comfort food feelings we get from television commercials. There are better-than-homemade tasting 85 cent snacks in every vending machine and gas station. We have billions of dollars worth of marketing giving us the perfect foods that our little hearts and big tummies desire.

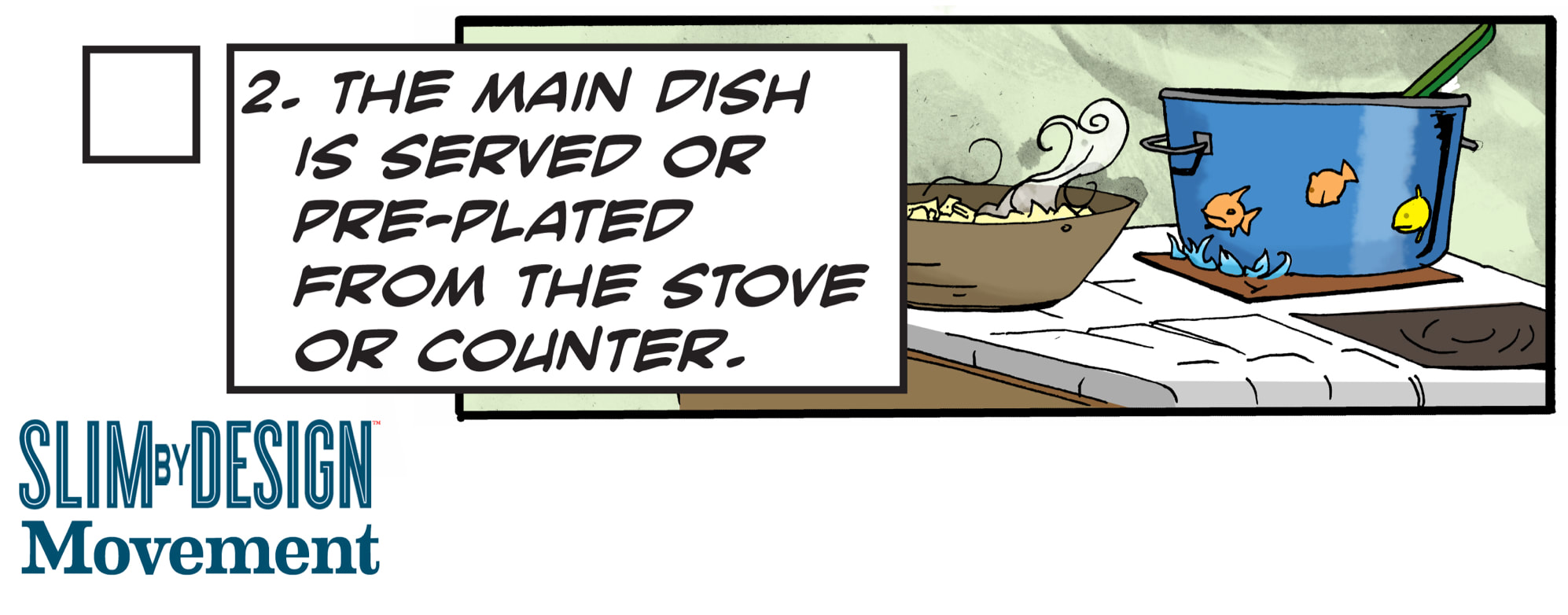

Yet before we blame those evil marketers let us look at the traps we set for ourselves. We make an extra “family-size” portion of pasta we make so no one goes hungry. We lovingly leave latch-key snacks on the table for our children (and ourselves). We use the nice, platter-size dinner plates that we can pile up with food. We heat up a piece of apple pie in the microwave while the lonely apple shivers in the crisper. Best intentions aside, we are Public Enemy #1 when it comes to booby-trapping the diets and willpower of both ourselves and our family.

The good news is that the same levers that almost invisibly lead you to slowly gain weight can also be pushed in the other direction to just as invisibly lead you to slowly lose weight. This will lead us to lose weight unknowingly. If we do not realize we are eating a little less than we need, we do not feel deprived. If we do not feel deprived, we are less likely to backslide and find ourselves overeating to compensate for everything we have forgone. The key lies in the Mindless Margin.

Our bodies fight against deprivation, and our brains fight against deprivation.[xviii] And to make matters worse, our day-to-day environment is set-up to booby-trap any half-hearted effort we can muster up. There are great smells on every fast food corner. There are warm, comfort food feelings we get from television commercials. There are better-than-homemade tasting 85 cent snacks in every vending machine and gas station. We have billions of dollars worth of marketing giving us the perfect foods that our little hearts and big tummies desire.

Yet before we blame those evil marketers let us look at the traps we set for ourselves. We make an extra “family-size” portion of pasta we make so no one goes hungry. We lovingly leave latch-key snacks on the table for our children (and ourselves). We use the nice, platter-size dinner plates that we can pile up with food. We heat up a piece of apple pie in the microwave while the lonely apple shivers in the crisper. Best intentions aside, we are Public Enemy #1 when it comes to booby-trapping the diets and willpower of both ourselves and our family.

The good news is that the same levers that almost invisibly lead you to slowly gain weight can also be pushed in the other direction to just as invisibly lead you to slowly lose weight. This will lead us to lose weight unknowingly. If we do not realize we are eating a little less than we need, we do not feel deprived. If we do not feel deprived, we are less likely to backslide and find ourselves overeating to compensate for everything we have forgone. The key lies in the Mindless Margin.

The Mindless Margin

No one goes to bed skinny and wakes up fat. Most people gain (or lose) weight so gradually they cannot really figure out how it happened. They do not remember changing their eating or exercise patterns.[xix] All they remember is once being able to fit into their favorite pants without having to hold their breathe and hope they can get the zipper to budge.

Sure, there are exceptions. If we gorge ourselves at the all-you-can-eat pizza buffet, then clean out the chip bowl at the Superbowl party, then stop by the Baskin-Robbins drive-through for a “Belly Buster” Sundae on the way home, we realize we have gone too far over the top. But on most days we have very little idea whether we have eaten 50 calories too much or 50 calories too little. In fact, most of us would not know if we ate 200 or 300 calories more or less than the day before.

This is the Mindless Margin. It is the margin or the zone in which we can either slightly overeat or slightly undereat without being aware of it. Suppose you can eat 2000 calories a day without either gaining or losing weight.[xx] If one day, however, you only ate 1000 calories, you would know it. You would feel weak, light-headed, cranky, and you would snap at the dog. On the other hand you would also know it if you ate 3000 calories. You would feel a little heavier, slower, and more like flopping on the couch and petting the cat.

If we eat way too little, we know it. If we eat way too much, we know it. But there is a calorie range – a Mindless Margin – where we feel fine and are unaware of small differences. That is, the difference between 1900 calories and 2000 calories is one we cannot detect, nor can we detect the difference between 2000 and 2100 calories. But over the course of a year, this mindless margin would either cause us to lose ten pounds or to gain ten pounds. It takes 3500 extra calories to equal one pound. It does not matter if we eat these extra 3500 calories in one week or gradually over the entire year. They will all add up to one pound.

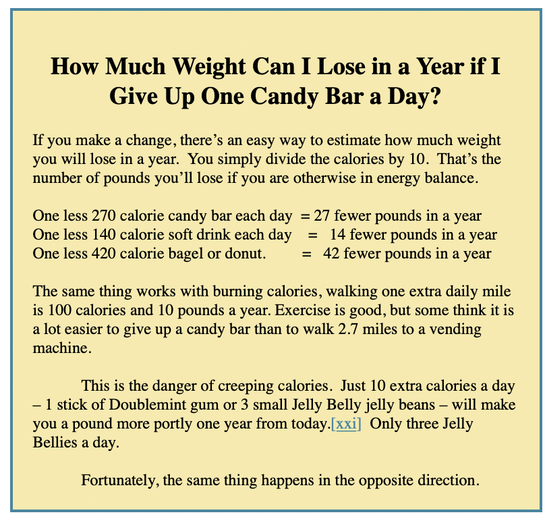

How Much Weight Will I Lose in a Year?

|

One colleague of mine, Stacy, had lost around 25 pounds during her first two years at a new job. When I asked how she lost the weight, she could not really answer. After some persistent questioning, it seemed that the only deliberate change she had made two years earlier was to give up caffeine. She switched from coffee to herbal tea. That did not seem to explain anything.

“Oh, yeah,” she said, “And because I gave up caffeine, I also stopped drinking Coke.” She had been drinking about six cans a week – far from a serious habit – but the 139 calories in each Coke translated into 14 pounds a year. When she quit, she was not even aware of why she had lost weight. In her mind all she had done was cut out caffeine. Herein lies the secret of the Mindless Margin. This Mindless Margin is that small range where we make slight changes to our routine that we hardly notice. Nevertheless, these changes can have a gradual – but eventually big – impact on our weight. They can make the difference between being 10 pounds heavier next New Years Day or 10 pounds lighter. Cutting out our favorite foods is a bad idea. Cutting down on how much we eat is mindlessly doable. Many fad diets focus more on the types of foods we can eat rather than how much we should eat. The problem is not that we order beef instead of a low-fat chicken breast. The problem is that the beef is often twice the size. A low-fat chicken breast that we resent having to eat is no better for our long-term diet than a tastier but slightly smaller piece of beef. If we are looking at only a 100 or 200 calories difference a day, these are not calories we will miss. We can trim them out of our day relatively easy – and unknowingly. The key is to do it unknowingly – mindlessly. |

We Either Gain or Lose Weight Every Day

In a classic article in Science, Drs. James O. Hill and John C. Peters showed that cutting only 100 calories a day from our diets will prevent weight gain in most of the US population.[xxii] The majority of people only gain a pound or two each year, and their calculations showed that anything a person does to make this 100 calorie difference will lead most of us to lose weight. We can do it by walking an extra 2000 steps each day (about one mile), or we can do it by eating 100 calories less than we otherwise would.

The best way to trim 100 or 200 calories a day is to do it in a way which does not make you feel deprived. It is so much easier to rearrange your kitchen and change a few eating habits so you do not have to think about eating less or differently. This is the silver lining to this dark, cloudy sky. The same things that lead us to mindlessly gain weight can also help us mindlessly lose weight.

How much weight? Unlike the 3:00 AM infomercials, it would not be 10 pounds in 10 hours, or 10 pounds in 10 days. It is not even going to be 10 pounds in 10 weeks. You would notice that, and you would feel deprived. Instead, suppose you stay within the Mindless Margin for losing weight and trim 100-200 calories a day. You would probably not feel deprived, but in 10 months you would be in the neighborhood of 10 pounds lighter. It would not put you in this year’s Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue, but it might put you back in some of your “signal” clothes, and it will make you feel better without costing you bread, pasta, and your comfort foods.

The best way to trim 100 or 200 calories a day is to do it in a way which does not make you feel deprived. It is so much easier to rearrange your kitchen and change a few eating habits so you do not have to think about eating less or differently. This is the silver lining to this dark, cloudy sky. The same things that lead us to mindlessly gain weight can also help us mindlessly lose weight.

How much weight? Unlike the 3:00 AM infomercials, it would not be 10 pounds in 10 hours, or 10 pounds in 10 days. It is not even going to be 10 pounds in 10 weeks. You would notice that, and you would feel deprived. Instead, suppose you stay within the Mindless Margin for losing weight and trim 100-200 calories a day. You would probably not feel deprived, but in 10 months you would be in the neighborhood of 10 pounds lighter. It would not put you in this year’s Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue, but it might put you back in some of your “signal” clothes, and it will make you feel better without costing you bread, pasta, and your comfort foods.

“I’m Not Hungry but I’m Going to Eat this Anyway.”

The acid test for mindless eating is wolfing down a food when we know we are not hungry. How many times have we done this? Most of us could start counting as recently as today.

Over coffee, a new friend commented that he had lost 30 pounds within the past year.[xxiii] When I asked him how, he explained he didn’t stop eating potato chips, pizza, or ice cream. He ate anything he wanted, but if he had a craving when he was not hungry he would say – out loud – “I’m not hungry but I’m going to eat this anyway.”

Having to make that declaration – out loud – would often be enough to prevent him from mindlessly indulging. Other times, he would take a nibble but be much more mindful of what he was doing.

The theme of Mindless Eating is that there are many things around us that manipulate or deceive us into eating more than we otherwise would. Popcorn buckets manipulate us, names confuse us, plates deceive us, friends unwittingly lead us astray, lighting and music fool us, colors miscue us, shapes trick us, and on and on. But all of them do so very subtly.

Mindless Eating helps you generate mindlessly-easy solutions to trim excess calories out of your life in a way in which you will not miss them. Each chapter specifically illustrates what researchers know about mindless eating, and each shows how you can use the same tricks to reverse how much you eat.

There are a lot of invisible traps out there that we unknowingly let trick us into overeating. What you can do is outlined in the next chapters, but we are first going to look at what causes us to decide how much we want to eat. Once we understand why we eat how much we eat, we can more clearly see how to change it.

Over coffee, a new friend commented that he had lost 30 pounds within the past year.[xxiii] When I asked him how, he explained he didn’t stop eating potato chips, pizza, or ice cream. He ate anything he wanted, but if he had a craving when he was not hungry he would say – out loud – “I’m not hungry but I’m going to eat this anyway.”

Having to make that declaration – out loud – would often be enough to prevent him from mindlessly indulging. Other times, he would take a nibble but be much more mindful of what he was doing.

The theme of Mindless Eating is that there are many things around us that manipulate or deceive us into eating more than we otherwise would. Popcorn buckets manipulate us, names confuse us, plates deceive us, friends unwittingly lead us astray, lighting and music fool us, colors miscue us, shapes trick us, and on and on. But all of them do so very subtly.

Mindless Eating helps you generate mindlessly-easy solutions to trim excess calories out of your life in a way in which you will not miss them. Each chapter specifically illustrates what researchers know about mindless eating, and each shows how you can use the same tricks to reverse how much you eat.

There are a lot of invisible traps out there that we unknowingly let trick us into overeating. What you can do is outlined in the next chapters, but we are first going to look at what causes us to decide how much we want to eat. Once we understand why we eat how much we eat, we can more clearly see how to change it.

Evidence-based Support and Published References

from Mindless Eating (Chapter 1)

[i] Brian Wansink, “Environmental Factors that Increase the Food Intake and Consumption Volume of Unknowing Consumers,” Annual Review of Nutrition (2004), vol. 24, pp. 455-479.

[ii] On average, those given the medium-size bucket at 61.1 grams while those given the large buckets at 93.5 grams. Nobody finished all of their popcorn, which had been popped in partially hydrogenated (meaning with "bad" trans fats) canola oil. This study was filmed for the ABC News Morning Edition. It can be viewed at www.MindlessEating.org. Excruciating detail about the study can be found in the related journal article: Brian Wansink and SeaBum Park, “At the Movies: How External Cues and Perceived Taste Impact Consumption Volume,” Food Quality and Preference, (January 2001) 12:1, 69-74.

[iii] While nearly everyone seems to be influenced by their environment, overweight people are even more sensitive to it than thin people. This is a curse and a blessing. Whereas overweight people are more influenced by things like bowl size, lighting, and what is going on around them, they can also benefit most when these things are changed. When these cues are removed, they eat a good deal less. That was the general topic of Stanley Schacter’s classic, but painfully titled 1974 book, Obese Humans and Rats, (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Potomac, Maryland). An nice update is Michael R. Lowe’s, “Stress-induced Eating in Restrained Eaters May Not Be Caused By Stress of Restraint,” Appetite, (January 2006), 46:1, 16-21.

[iv] Legions of researchers have studied portion size, but the two most associated with it in the nutritional sciences are Drs. Barbara Rolls and LeAnn Birch, both at Pennsylvania State University. Three of the classic studies in this area include the following: Barbara J. Rolls, Dianne Engell, and LeAnn L. Birch, “Serving Portion Size Influences 5-Year-Old but Not 3-Year-Old Children's Food Intakes, (2000), 100, 32-34. LeAnn L. Birch, Linda McPhee, B. C. Shoba, Lois Steinberg, and Ruth Krehbiel, “Clean up Your Plate: Effects of Child Feeding Practices on the Conditioning of Meal Size,” Learning and Motivation (1987), 18, 301-17.

[v] The Spice Box Restaurant can be found in Bevier Hall on the campus of the University of Illinois in Urbana, Illinois. It is open January through April and reservations can be made by calling 217-333-6520. While it used to only open on Thursdays, it recently changed its dinner schedule to Tuesdays and Fridays. The article described here is: Brian Wansink, Collin Payne, Jill North, and James E. Painter,"Fine as North Dakota Wine: Sensory Experiences and Food Intake," under review, Physiology and Behavior (2004).

[vi] More recently the studies in the Spice Box have been more survey-based and have focused on meal evaluations and perceptions of value.

[vii] Special mega-cudos to Jill North, co-author and manager of the Fine Dining Program. After we had designed the study, designed the labels, purchased the wine, and set up the experimental protocol, I was called out of the country shortly before the study was scheduled. Instead of postponing it, she managed to pull it off in one long evening with the help of the rest of our team.

[viii] When a study takes place over many different days, we usually get permission to give a detailed debriefing by email only when the entire study is completed.

[ix] This paper has four separate studies in it that illustrate shopping psychology in action. It basically does not matter what a sign in a grocery store says, if has a number in it – “Limit 12,” “3 for $3,” “Buy 18 for the Weekend” – it lead us to buy 30-100% more than they normally would. We basically anchor, or fixate, on the number the sign suggests, and we end up being biased by this “opening bid.” The paper is Brian Wansink, Robert J. Kent, and Stephen J. Hoch, “An Anchoring and Adjustment Model of Purchase Quantity Decisions,” Journal of Marketing Research (February 1998), 35:1, 71-81.

[x] The speed at which you regain weight after going off a diet is almost always directly related to the speed you lost the weight to begin with. If you miraculously lose 10 pounds in 2 days with the new Celebrity Fad Diet, you are likely to miraculously gain it back almost as fast.

[xi] See Maureen T. Mcguire, Rita R. Wing, Mary L. Klem and James O. Hill, “What predicts weight regain in a group of successful weight losers?” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology (1999), 67:2, 177-185.

[xii] Quotations were adopted from “Last-Minute Diet Secrets, People, March 16, 2004, pp. 122-5.

[xiii] This conclusion from a series of studies is alluded to in David A. Levitsky, “The Non-regulation of Food Intake in Humans: Hope for Reversing the Epidemic of Obesity,” Physiology & Behavior (December 2005), 86:5, 623-632.

[xiv] Much of the best work of restrained eaters has been conducted by Janet Polivy and C. Peter Herman. A typical example of this is Janet Polivy, J. Coleman and C. Peter Herman, “The Effect of Deprivation on Food Cravings and Eating Behavior in Restrained and Unrestrained Eaters,” International Journal of Eating Disorders(December 2005), 38:4, 301-309.

[xv] This syndicated column was widely reprinted with the name of the nationally-known psychologist. This account was taken from “News of the Weird,” Funny times, October 2005, p. 25. Lisa G. Berzins,

[xvi] John P. Foreyt, “Need for Lifestyle Intervention: How to Begin,” American Journal of Cardiology, (August 22, 2005), 96:4A, pp. 11-14.

[xvii] What is interesting is that most people initially think they only make an average of less than 30 of these decisions. It’s evidence of how mindless they are. More can be found in Brian Wansink and Colin R. Payne (2006), “Estimates of Food-related Decisions Across BMI,” under review at Psychological Reports.

[xviii] The best current thinking on this is being done by Roy Baumeister. See Roy F. Baumeister, “Yielding to Temptation: Self-Control Failure, Impulsive Purchasing, and Consumer Behavior,” Journal of Consumer Research (2002), 28:4, 670-76. Other work in the marketing area include that by Erica M. Okada, “Justification Effects on Consumer Choice of Hedonic and Utilitarian Goods,” Journal of Marketing Research (2005), 42:1, 43-53, and by Baba Shiv and Alexander Fedorikhin, “Heart and Mind in Conflict: The Interplay of Affect and Cognition in Consumer Decision Making,” Journal of Consumer Research (December 1999), 26, 278-92.

[xix] N. E. Sherwood, Robert W. Jeffry, Simone French, et al., “Predictors of Weight Gain in the Pound of Prevention Study,” International Journal of Obesity (April 2000), 24:4, 395-403.

[xx] If you burn off the same number of calories each day as you eat, you are “in energy balance.” The exact number of calories you need to be in energy balance varies depending on your weight and how much you move during the day. Smaller adults burn fewer calories a day than larger adults; active people more than inactive people.

[xxi] A pound is roughly equivalent to 3500 calories. Eating three Jelly Belly jelly beans a day (12 calories) would lead to are 4380 over the year. Similarly drinking one less can of Coca-Cola (139 calories) each day would amount to 101,470 calories – 29 lbs. – over a 2 year period.

[xxii] Details can be found in James O. Hill and John C. Peters (1998), “Environmental contributions to the obesity epidemic,” Science, 280 (5368): 1371-1374.

[xxiii] This person, Jay S. Walker, also supplemented this with lots and lots of exercise.

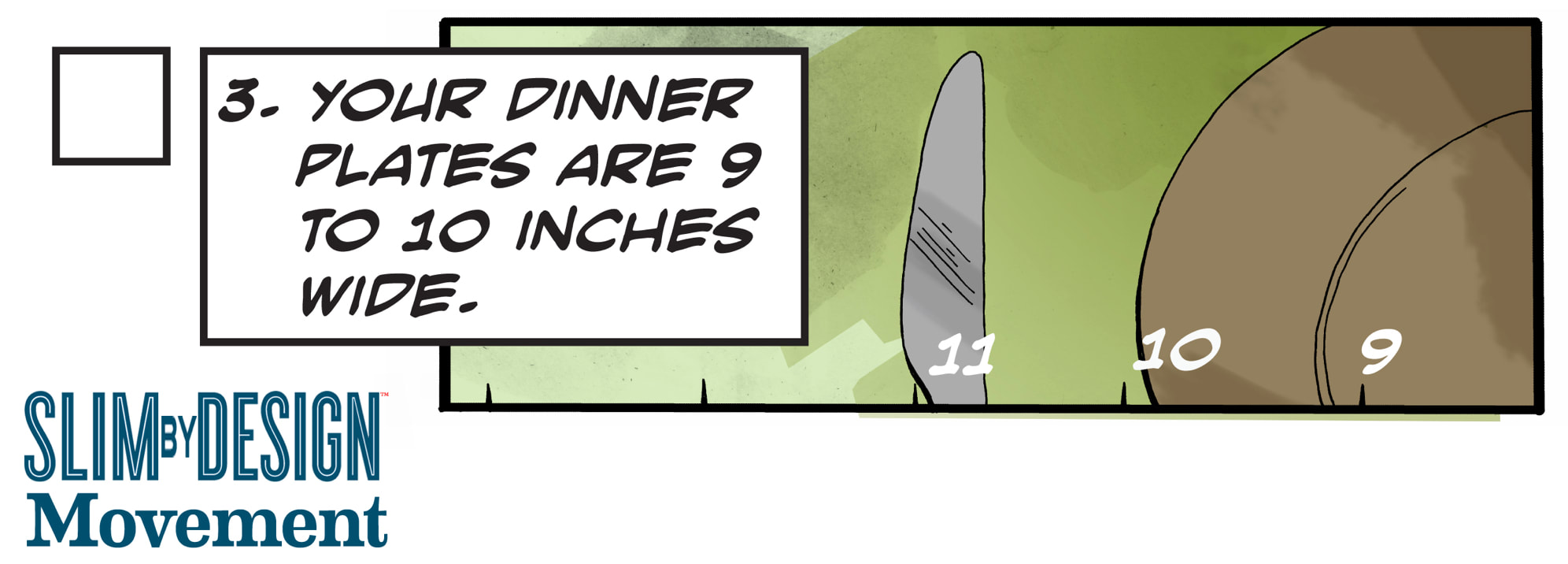

[xxiv] Our sins of dietary excess can be compared to those of French people (French Women Don’t Get Fat), tropical people (The Tropical Diet), Mediterranean people (The Mediterranean Diet), and even Okinawans (The Okinawa Diet Plan).

Learn more about your food radius• Nobody goes to a restaurant to start a diet • Our best and worst eating habits start in the grocery store • Where you work can either make you heavy or healthy. • In school lunchrooms: It's not nutrition until it's eaten. |