Your Healthy Shopping Hacks

|

Shopping should be fun; not a chore. Pick a couple new shopping hacks, so you can go back to having fun.

|

| |||||||

Knowing Shopping Psychology Will Make You Healthier

You’ve never seen a Kleenex Cam. That’s why it works so well--it sees you, but you don’t see it. It’s helped us learn why the crazy things grocery shoppers do aren’t as crazy as they seem.

Back in 2001, I asked some clever engineering students at the University of Illinois to rig up a small, remote digital movie camera into what looked like an ordinary box of Kleenex,[1] Using this invisible camera we could follow shoppers to learn exactly how they shop.[2] We took our Kleenex Cams and stacked them on top of “deserted” shopping carts, hid them on shelves next to Fruity Pebbles cereal, and positioned them in our carts so we could follow shoppers as they moved through the aisles. The Kleenex Cams showed us what catches a person’s eye, what they pick up and put back, why they buy things they’ll never use,[3] why shopping lists don’t matter, and how they shop differently in the “smelly” parts of a grocery store. Again, these studies are all university-approved.[4]

But let’s back up and set the stage. Our best and worst eating habits start in a grocery store. Food that’s bought here gets moved into our homes. Food in our homes gets eaten.[5] If we bought more bags of fruit and fewer boxes of Froot Loops, we would eventually eat more of the first and less of the second. Although bad for the Froot Loops Corporation, it’s great for us--and great for grocery stores. The typical grocery store makes more profit by selling you $10 more fruit than $10 more Froot Loops. There’s a higher mark-up on fruit, and--unlike the everlasting box of Froot Loops[6]--fruit spoils, and spoiled fruit spoils profits. You have to sell it while you can.

So if a grocery store makes more by selling healthy foods like fruit, why don’t they do a better job of it? They try--but what they really need is a healthy dose of redesign.

We’ve been following grocery shoppers since 1995, and some things have changed since then. For one, we no longer have to wrestle with the bulky Kleenex-Cams. Our newer cameras are so small they’re embedded into Aquafina water bottles with false bottoms.[7] The technology is sexier, but the results are e-x-a-c-t-l-y the same.[8] Wherever we’ve done these studies--corner markets in Philadelphia or warehouse stores in France, Brazilian superstores or Taiwanese night markets--people pretty much shop in the same time-stressed, sensory-overwhelmed way. But knowing what can be done to get them to buy a healthier cartful of food is good for shoppers, for grocers, and even for governments.

Wait. Governments?

What jump-started a lot of our recent thinking was a request we received from the Danish government. In April 2011, they sent a six-person delegation out to my Lab. Their mission: To help Danish grocery stores make it easier for shoppers to shop healthier. Our mission, should we choose to accept it: Develop a healthy supermarket makeover plan that would be cheap, easy, and profitable for Danish grocery stores to implement. Our makeover plan had to be profitable for stores because that’s the only way it would work. But here’s the cool clincher: They’d give us an entire island on which to test our plan.

Back in 2001, I asked some clever engineering students at the University of Illinois to rig up a small, remote digital movie camera into what looked like an ordinary box of Kleenex,[1] Using this invisible camera we could follow shoppers to learn exactly how they shop.[2] We took our Kleenex Cams and stacked them on top of “deserted” shopping carts, hid them on shelves next to Fruity Pebbles cereal, and positioned them in our carts so we could follow shoppers as they moved through the aisles. The Kleenex Cams showed us what catches a person’s eye, what they pick up and put back, why they buy things they’ll never use,[3] why shopping lists don’t matter, and how they shop differently in the “smelly” parts of a grocery store. Again, these studies are all university-approved.[4]

But let’s back up and set the stage. Our best and worst eating habits start in a grocery store. Food that’s bought here gets moved into our homes. Food in our homes gets eaten.[5] If we bought more bags of fruit and fewer boxes of Froot Loops, we would eventually eat more of the first and less of the second. Although bad for the Froot Loops Corporation, it’s great for us--and great for grocery stores. The typical grocery store makes more profit by selling you $10 more fruit than $10 more Froot Loops. There’s a higher mark-up on fruit, and--unlike the everlasting box of Froot Loops[6]--fruit spoils, and spoiled fruit spoils profits. You have to sell it while you can.

So if a grocery store makes more by selling healthy foods like fruit, why don’t they do a better job of it? They try--but what they really need is a healthy dose of redesign.

We’ve been following grocery shoppers since 1995, and some things have changed since then. For one, we no longer have to wrestle with the bulky Kleenex-Cams. Our newer cameras are so small they’re embedded into Aquafina water bottles with false bottoms.[7] The technology is sexier, but the results are e-x-a-c-t-l-y the same.[8] Wherever we’ve done these studies--corner markets in Philadelphia or warehouse stores in France, Brazilian superstores or Taiwanese night markets--people pretty much shop in the same time-stressed, sensory-overwhelmed way. But knowing what can be done to get them to buy a healthier cartful of food is good for shoppers, for grocers, and even for governments.

Wait. Governments?

What jump-started a lot of our recent thinking was a request we received from the Danish government. In April 2011, they sent a six-person delegation out to my Lab. Their mission: To help Danish grocery stores make it easier for shoppers to shop healthier. Our mission, should we choose to accept it: Develop a healthy supermarket makeover plan that would be cheap, easy, and profitable for Danish grocery stores to implement. Our makeover plan had to be profitable for stores because that’s the only way it would work. But here’s the cool clincher: They’d give us an entire island on which to test our plan.

The Desserted Island of DenmarkBornhold is a Danish island with 42,000 inhabitants that sits in the Baltic Sea, 100 miles east of Copenhagen[9]. The government of Denmark wanted us to help change the grocery stores on the entire island so they could profitably help these islanders shop healthier. They wanted to turn it from a Dessert Isle into a Salad Aisle.

Anyone who’s read or seen H.G. Wells’ The Island of Dr. Moreau knows that islands are a researcher’s dream. You can do all sorts of crazy, mad scientist things on them and not worry about the rest of the world bothering you. You can change the shopping carts or layout of all the stores on the island, and if the sales of Crisco and Pixy Stix drop by 20 percent, you know it’s not because people are swimming over to buy them in Lapland. |

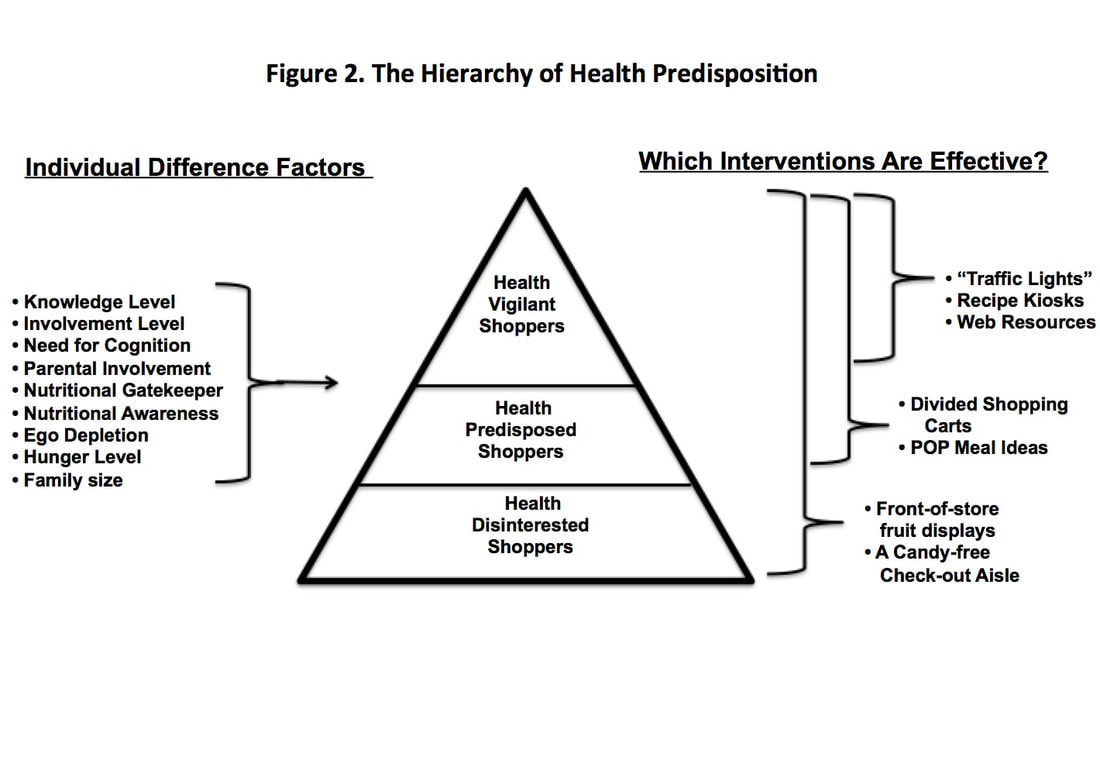

Until they came to talk with us, the Danish government was considering three types of changes: Tax it, take it, or teach it.[10] But taxing food or taking it away creates pushback. Shoppers don’t like it, grocers don’t like it, and so it can often backfire. For instance, when we did a six-month study on taxing soft drinks in the United States, we found that the only people who bought fewer soft drinks were beer-buying households—and they just bought a lot more beer.[11] People had to drink something with their pizza and burgers, and it wasn’t going to be tap water or soymilk. They changed from Coke to Coors.

And teaching doesn’t work much better.[12] Shoppers don’t behave the way we’re supposed to because 1) we love tasty food, and 2) we don’t like to think more than we have to. Because of our love for both tasty food and for mindless shopping, we don’t approach grocery shopping like a nutrition assignment. We just do it and move on to the next 57 items on our to-do list. With this mindless mindset, when we’re shopping at 5:45 on a Friday evening we’re not about to be fazed by there being a few more calories in pizza crust than in pita bread.

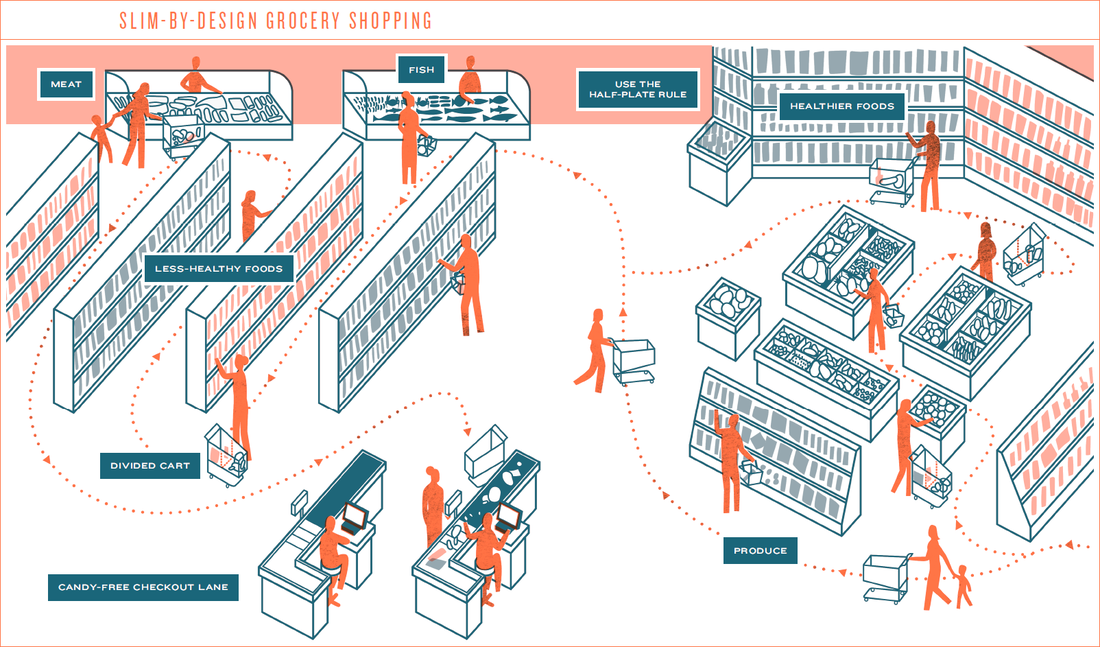

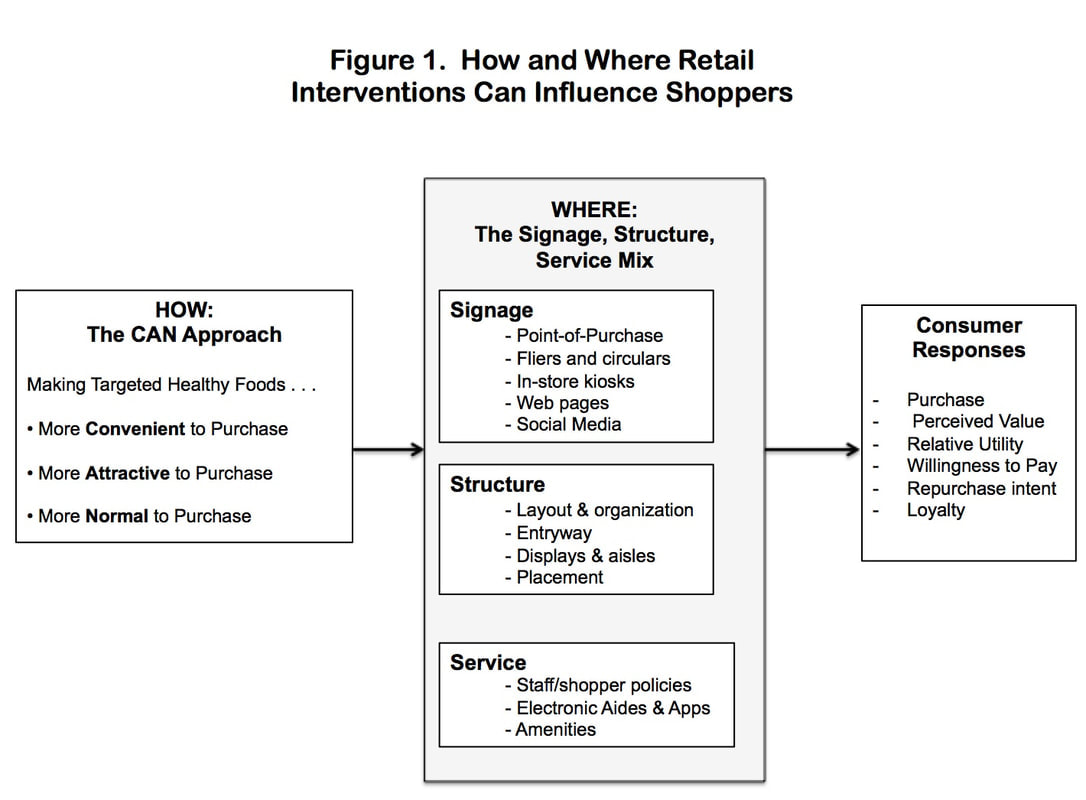

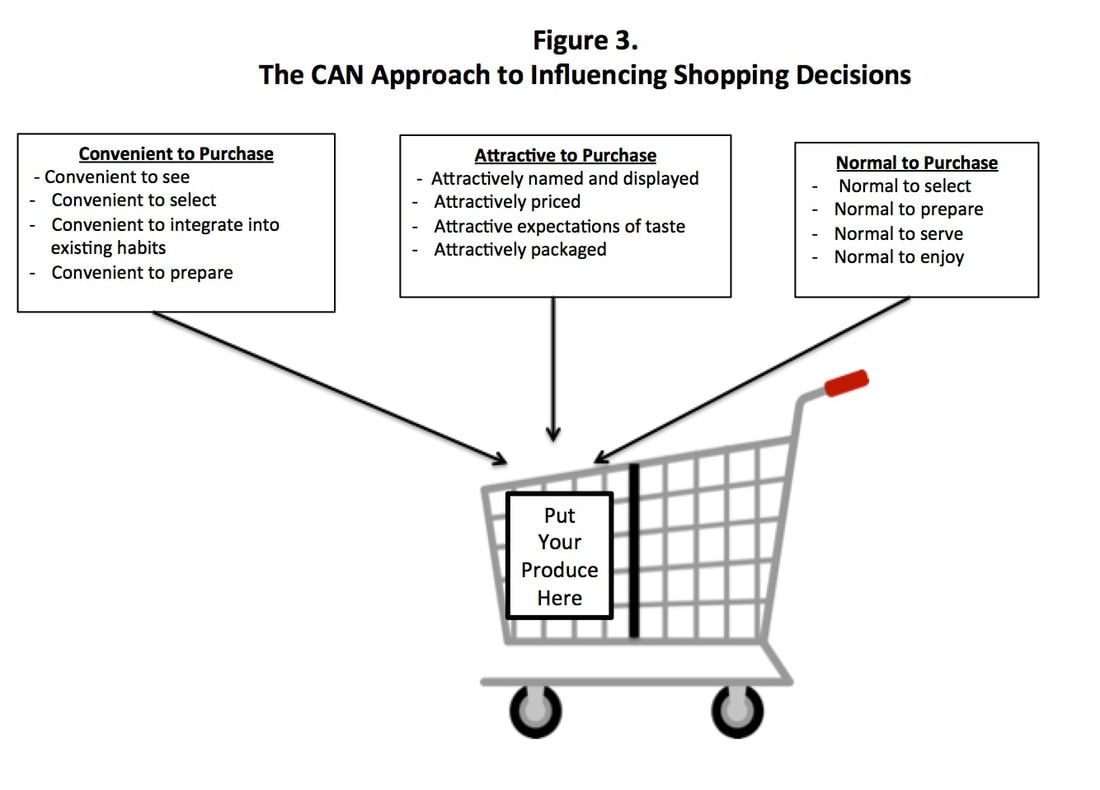

Maybe the best way we can change grocery shopping habits is to make them more mindlessly healthy--make it more convenient, attractive, and normal to pick up and buy a healthier food. [13] So here’s what we did in Bornholm. Based on our “Kleenex Cam” recordings,[14] notes, stopwatch times, and data for thousands of similar shoppers, we focused on design changes in five areas of the store: carts, layouts, aisles, signs, and checkout lines. We had two criteria: 1) all the changes had to make the store more money in a month than they cost to implement, and 2) they all had to help make people slim by design. Let’s start with a shopping cart.

And teaching doesn’t work much better.[12] Shoppers don’t behave the way we’re supposed to because 1) we love tasty food, and 2) we don’t like to think more than we have to. Because of our love for both tasty food and for mindless shopping, we don’t approach grocery shopping like a nutrition assignment. We just do it and move on to the next 57 items on our to-do list. With this mindless mindset, when we’re shopping at 5:45 on a Friday evening we’re not about to be fazed by there being a few more calories in pizza crust than in pita bread.

Maybe the best way we can change grocery shopping habits is to make them more mindlessly healthy--make it more convenient, attractive, and normal to pick up and buy a healthier food. [13] So here’s what we did in Bornholm. Based on our “Kleenex Cam” recordings,[14] notes, stopwatch times, and data for thousands of similar shoppers, we focused on design changes in five areas of the store: carts, layouts, aisles, signs, and checkout lines. We had two criteria: 1) all the changes had to make the store more money in a month than they cost to implement, and 2) they all had to help make people slim by design. Let’s start with a shopping cart.

A Half-cart Solution

|

Here’s a ten-word description of how most people shop for groceries: They throw things in their cart and they check out. What’s the right amount of fruits and vegetables to put in a cart? We don’t really know because we don’t really care. Yet imagine what would happen if every time we put something in our cart we had to ask ourselves whether it was healthy or not. It’d be irritating--for sure--but after a while we’d think twice about what we casually threw in. Just stopping and thinking for a split second would be enough to snap us out of our mindlessly habitual zombie shopping trance. [15],[16]

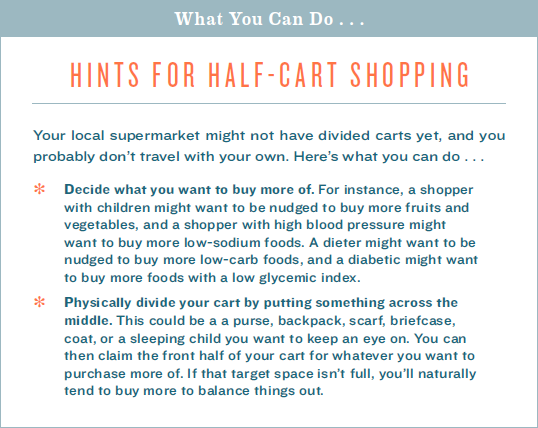

Back to the cart. When most of us shop, fruits and vegetables take up only 24 percent of our cart.[17] But suppose your grocery store sectioned a cart in half by taping a piece of yellow duct tape across the middle interior of the cart. And suppose they put a sign in the front of the cart that recommended that you put all the fruits and vegetables in the front and all the other foods in the back. This dividing line in the cart doesn’t moralize or lecture. It just encourages shoppers to ask themselves whether the food in their hand goes in the front or back of the cart. There’s nothing to resist or rage against--they’re simply sorting their food. The Miracle of Duct-Tape: When it’s used at home, you become MacGyver. When it’s used to divide your grocery cart, you become healthier. People who shop with divided carts that suggest they put their fruits and vegetables in the front buy 23 percent more of them.[18]. Do it yourself. Divide your cart with your coat, your purse, or your briefcase. Or bring your own duct tape. We made a few dozen of these divided carts to test at supermarkets in Williamsburg, Virginia, and Toronto, Canada.[19] When people finished shopping and returned their souped-up, tricked-out carts, we gave them a gift card to a local coffee shop if they would answer some questions and give us their shopping receipt. Shoppers with these divided carts spent twice as much on fruits and vegetables. They also spent more at the store--about 25 percent more. Not only did this fruit and vegetable divider make them think twice about what they bought, it also made them believe that buying more fruits and vegetables was normal. Who knows how much healthy stuff your neighbor buys? It must be about half, people think as they throw in some pears and three more red peppers. |

Healthy First and Green Line Guides

When you walk up to a buffet, you’re 11 percent more likely to take the first vegetable you see than the third.[20] When opening your cupboard, you’re three times as likely to take the first cereal you see as you are the fifth.[21] The same is true in grocery stores. When you start shopping, you can’t wait to start piling things in your cart. But after it starts filling up, you become more selective. If stores could get you to walk by more of the healthy--and profitable--foods first, they might be able to get you to fill up the cart on the good stuff, and squeeze out any room for the Ben & Jerry’s variety pack.

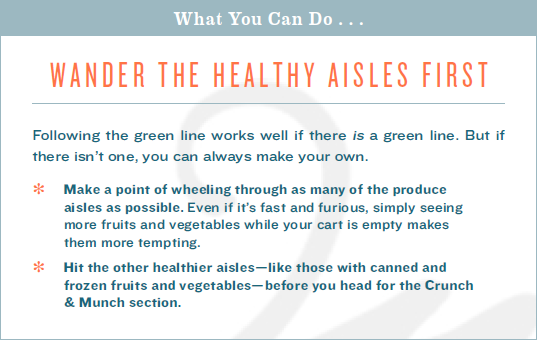

Most grocery stores in the United States place the fruit and vegetable section on the far right of the store. It’s the first thing we see and wander over to. The bad news is that we spend only about 6 minutes there.[22] We pick up some apples and lettuce and then wander over to the next aisle. But if stores could get us to linger there a little longer, we’d buy a little bit more.

The secret might lie in the fact that we’re wanderers--we’re not always very deliberate. What if we put a dashed green line that zig-zagged through the produce section, and what if they were to put floor decals in front of food shelves that offer healthy meal ideas? Just like that dashed yellow line on the highway that keeps you mindlessly on the road and the billboards that keep you mindlessly amused, maybe putting a dashed green line and floor decals might also keep us wandering the produce section a bit longer.

To test this, we proposed Operation: Green Highway. Supermarkets could put a 2-inch-wide dashed green line through the produce section--around the apples and oranges, over to the lettuce, past the onions and herbs, and back around to the berries and kumquats. They could even include some kid-friendly visuals or floor graphics. If a shopper followed this green highway, he or she might be tempted to buy more fruits and vegetables.

To test this, we had people trace their way through grocery stores that either did or did not have Health Highway lines. Did people stay on the line? Of course not, but they would have spent an average equivalent of three more minutes in the produce section. At about $1/minute, this would mean they could spend as much as $3 more on fruits and vegetables than they otherwise would have.[23] [24]

But what about the other store aisles? Let’s say that you have two favorite grocery stores: TOPS and Hannaford. At TOPS, the first aisle after the produce section--let's call it Aisle 1--is the potato chips, cookies, and soft drinks aisle. At Hannaford the potato chips, cookies, and soft drinks are in Aisle 15--the second-to-last aisle in the store. If you’re on a diet, which store should you choose?

We followed 260 shoppers in Washington, DC, grocery stores to see if a person shops differently depending on which aisle they’re in.[25] We discovered that most people with shopping carts behave the same way: They walk through the produce section, then turn and go down Aisle 1 (which leads back toward the front of the store). It almost doesn’t matter what’s in the aisle--health food, dog food, or mops. At this point, shopping’s still a fun adventure. But after Aisle 1, shoppers get mission-oriented and start skipping aisles as they look for only what they think they need. So, Aisle 1 gets the most love from shoppers.

So, what’s in Aisle 1 at your favorite grocery store? It’s often soft drinks, chips, or cookies. To make a grocery store more slim by design, managers could easily load up this first aisle with whatever healthier food is most profitable for them. This might be store-brand canned vegetables, whole-grain foods, or high-margin lower-calorie foods. First in sight is first in cart.

Most grocery stores in the United States place the fruit and vegetable section on the far right of the store. It’s the first thing we see and wander over to. The bad news is that we spend only about 6 minutes there.[22] We pick up some apples and lettuce and then wander over to the next aisle. But if stores could get us to linger there a little longer, we’d buy a little bit more.

The secret might lie in the fact that we’re wanderers--we’re not always very deliberate. What if we put a dashed green line that zig-zagged through the produce section, and what if they were to put floor decals in front of food shelves that offer healthy meal ideas? Just like that dashed yellow line on the highway that keeps you mindlessly on the road and the billboards that keep you mindlessly amused, maybe putting a dashed green line and floor decals might also keep us wandering the produce section a bit longer.

To test this, we proposed Operation: Green Highway. Supermarkets could put a 2-inch-wide dashed green line through the produce section--around the apples and oranges, over to the lettuce, past the onions and herbs, and back around to the berries and kumquats. They could even include some kid-friendly visuals or floor graphics. If a shopper followed this green highway, he or she might be tempted to buy more fruits and vegetables.

To test this, we had people trace their way through grocery stores that either did or did not have Health Highway lines. Did people stay on the line? Of course not, but they would have spent an average equivalent of three more minutes in the produce section. At about $1/minute, this would mean they could spend as much as $3 more on fruits and vegetables than they otherwise would have.[23] [24]

But what about the other store aisles? Let’s say that you have two favorite grocery stores: TOPS and Hannaford. At TOPS, the first aisle after the produce section--let's call it Aisle 1--is the potato chips, cookies, and soft drinks aisle. At Hannaford the potato chips, cookies, and soft drinks are in Aisle 15--the second-to-last aisle in the store. If you’re on a diet, which store should you choose?

We followed 260 shoppers in Washington, DC, grocery stores to see if a person shops differently depending on which aisle they’re in.[25] We discovered that most people with shopping carts behave the same way: They walk through the produce section, then turn and go down Aisle 1 (which leads back toward the front of the store). It almost doesn’t matter what’s in the aisle--health food, dog food, or mops. At this point, shopping’s still a fun adventure. But after Aisle 1, shoppers get mission-oriented and start skipping aisles as they look for only what they think they need. So, Aisle 1 gets the most love from shoppers.

So, what’s in Aisle 1 at your favorite grocery store? It’s often soft drinks, chips, or cookies. To make a grocery store more slim by design, managers could easily load up this first aisle with whatever healthier food is most profitable for them. This might be store-brand canned vegetables, whole-grain foods, or high-margin lower-calorie foods. First in sight is first in cart.

Wide Aisles and High Products[26]

|

The more time you spend in a store, the more you buy. Similarly, the more time you spend in an aisle, the more you buy.[27] In order for us to buy a healthy food, we need to a) see it and b) have the time to pick it off the shelf.

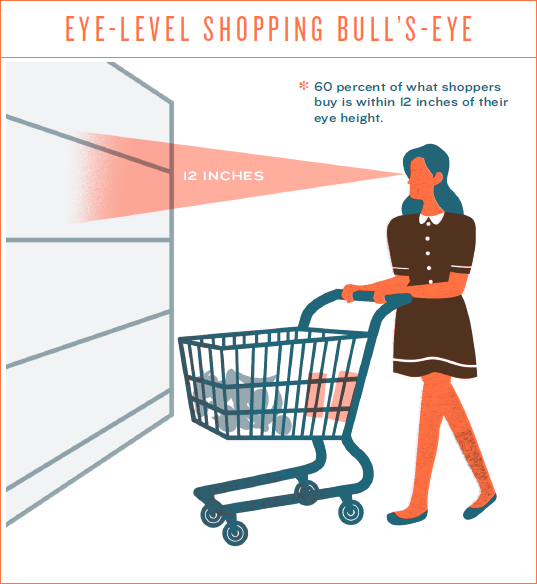

But not all shelves are the same. Food placed at eye level is easier to spot and buy. For instance, kids’ foods are placed at their eye level, so that they can irritate us into buying it (“I want it! I want it! I want it!”). This works for Fruity Pebbles and our kid, but would it for kale chips and us? We returned to our “I-Spy” habits and observed 422 people purchasing thousands of products in the Washington, DC, area. First we estimated the height of each shopper using a series of pre-marked shelves they walked by (picture those height marker decals on the doors of convenience stores).[28] We then measured the height of each product they looked at. Based on where they looked, we could figure out what percent of the foods they bought were at eye level.[29] If you’re shopping in a narrow aisle, 61 percent of everything you’ll buy is within one foot of your eye level—either one foot above or one foot below.[30] This is useful to know if you’re a grocery store owner who wants to sell us healthier foods. Smart store managers can put these profitable healthy foods at eyeball level. If the product is one that’s typically bought by males, it can be placed even 5 inches higher, since the average male is that much taller than the average female. |

One well-known finding among people watchers is that nothing causes a person to scoot out of an aisle fast than when someone accidentally brushes against their behind. In his book Why We Buy, Paco Underhill refers to this as the “butt brush.”[31] Think of the last time this happened to you--five seconds later you had pretty much teleported yourself to another spot in the store. Since brushing against people probably happens much more in narrow grocery store aisles than wide ones, people might spend less time and buy fewer items there. Many grocery store aisles range from 6 to 8 feet wide. In the DC grocery stores mentioned earlier, we measured the width of all the aisles and timed how long the average shopper spent in them. Indeed, the wider the aisle, the more they bought. It didn’t matter what was there--canned Brussels sprouts, 20-pound bags of cat food, dishwashing liquid--the more time they spent in the aisles, the more items they bought.[32]

Your grocer could put more healthy food in wider aisles and less healthy food in narrower ones. Identifying or creating healthy food aisles that are wider would be one solution. Another solution--make sure the healthier foods are at eye level.[33]

Your grocer could put more healthy food in wider aisles and less healthy food in narrower ones. Identifying or creating healthy food aisles that are wider would be one solution. Another solution--make sure the healthier foods are at eye level.[33]

Groceries and Gum

Most of us know that it’s a bad personal policy to go shopping on an empty stomach. We think it’s because we buy more food when we’re hungry—but we don’t. In our studies of starving shoppers, they buy the exact same amount of food as stuffed shoppers. They don’t buy more, but they buy worse.[34] When we’re hungry, we buy foods that are convenient enough to eat right away and stop our cravings.[35] We don’t go for broccoli and tilapia; we go for carbs in a box or bag. We go for one of the “Four Cs”: crackers, chips, cereal, or candy. We want packages we can open and eat from with our right hand while we drive home with our left.

When it comes to cravings, our imagination is the problem. The cravings hit us super hard when we’re hungry because our hunger leads us to imagine what a food would feel like in our mouth if we were eating it. If your Girl Scout neighbor asked you to buy Girl Scout cookies, we’d buy one or two boxes. But if she were to instead ask us to describe what it’s like to eat our favorite Girl Scout cookie, we would start imagining the texture, taste, and chewing sensation, and wind up ordering every life-giving box of Samoas she could carry. (Keep this in mind the next time your daughter wants to win the Gold Medal in cookie sales.)

Most food cravings--including those when we shop--are largely mental. As with the Girl Scout cookies, they seem to be caused when we imagine the sensory details of eating a food we love--we start imagining the texture, taste, and chewing sensation. But if we could interrupt our imagination, it might be easier to walk on by.

One way we can interrupt these cravings is by simply chewing gum. Chewing gum short-circuits our cravings. It makes it too hard to imagine the sensory details of crunchy chips or creamy ice cream. My colleague Aner Tal and I discovered this when we gave gum to shoppers at the start of their shopping trip. When we reconnected with them at the end of their trip, they rated themselves as less hungry and less tempted by food--and in another study we found they also bought 7 percent less junk food then those who weren’t chewing gum.[36] If you shop for groceries just before dinner, make sure the first thing you buy is gum--and our early findings show that sugarless bubblegum works best.

When it comes to cravings, our imagination is the problem. The cravings hit us super hard when we’re hungry because our hunger leads us to imagine what a food would feel like in our mouth if we were eating it. If your Girl Scout neighbor asked you to buy Girl Scout cookies, we’d buy one or two boxes. But if she were to instead ask us to describe what it’s like to eat our favorite Girl Scout cookie, we would start imagining the texture, taste, and chewing sensation, and wind up ordering every life-giving box of Samoas she could carry. (Keep this in mind the next time your daughter wants to win the Gold Medal in cookie sales.)

Most food cravings--including those when we shop--are largely mental. As with the Girl Scout cookies, they seem to be caused when we imagine the sensory details of eating a food we love--we start imagining the texture, taste, and chewing sensation. But if we could interrupt our imagination, it might be easier to walk on by.

One way we can interrupt these cravings is by simply chewing gum. Chewing gum short-circuits our cravings. It makes it too hard to imagine the sensory details of crunchy chips or creamy ice cream. My colleague Aner Tal and I discovered this when we gave gum to shoppers at the start of their shopping trip. When we reconnected with them at the end of their trip, they rated themselves as less hungry and less tempted by food--and in another study we found they also bought 7 percent less junk food then those who weren’t chewing gum.[36] If you shop for groceries just before dinner, make sure the first thing you buy is gum--and our early findings show that sugarless bubblegum works best.

Using the Half-plate Rule

Each spring, Wegman’s, a popular grocery chain in the Northeast, does a big health promotion push called “Eat well. Live well.” We’ve worked with them often to give them new ideas to try in their stores. In 2009, they drove down to our Lab to see if we could develop a program that would get their own employees to eat more fruit and vegetables. They were thinking of giving them some sort of education or promotion program. We were thinking of giving them a simple, visual, rule-of-thumb. What we told them worked great for them, and it can work great for you both in the store and especially at home.

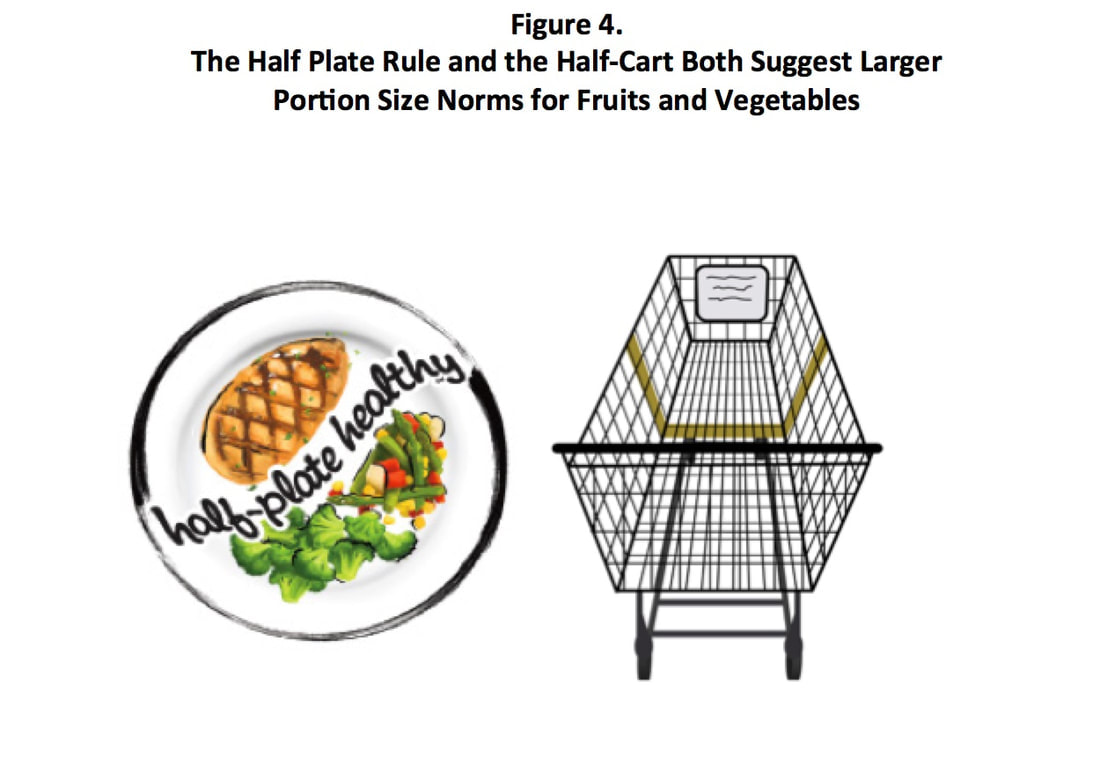

In the good old days when we were kids, eating was easy. Your grandmother piled dishes of food on the table, you’d take a little of each, and--ta-da--that was nutrition! Today, the 273-page United States Dietary Guidelines tips the scale at almost three pounds. But there’s an easier way for most people. When I was the executive director in charge of the Dietary Guidelines and people asked me how they should eat, I usually told them to simply use the Half-Plate Rule.[40] Half of their plate had to be filled with fruit, vegetables, or salad, and the other half could be anything they wanted. It could be lamb, a blueberry muffin, a handful of cheese . . . anything. They could also take as many plates of food as they wanted. It’s just that every time they went back for seconds or thirds, half their plate still had to be filled with fruit, vegetables, or salad.

Could a person load up half of their plate with Slim Jims and pork belly? Sure, but they don’t. Giving people freedom – a license to eat with only one simple guideline--seems to keep them in check. There’s nothing to rebel against, resist, or work around. As a result, they don’t even try. They also don’t seem to overeat.[41] They may want more pasta and meatballs or another piece of pizza, but if they also have to balance this with a half-plate of fruit, vegetables, or salad, many people decide they don’t want it bad enough.[42]

In the good old days when we were kids, eating was easy. Your grandmother piled dishes of food on the table, you’d take a little of each, and--ta-da--that was nutrition! Today, the 273-page United States Dietary Guidelines tips the scale at almost three pounds. But there’s an easier way for most people. When I was the executive director in charge of the Dietary Guidelines and people asked me how they should eat, I usually told them to simply use the Half-Plate Rule.[40] Half of their plate had to be filled with fruit, vegetables, or salad, and the other half could be anything they wanted. It could be lamb, a blueberry muffin, a handful of cheese . . . anything. They could also take as many plates of food as they wanted. It’s just that every time they went back for seconds or thirds, half their plate still had to be filled with fruit, vegetables, or salad.

Could a person load up half of their plate with Slim Jims and pork belly? Sure, but they don’t. Giving people freedom – a license to eat with only one simple guideline--seems to keep them in check. There’s nothing to rebel against, resist, or work around. As a result, they don’t even try. They also don’t seem to overeat.[41] They may want more pasta and meatballs or another piece of pizza, but if they also have to balance this with a half-plate of fruit, vegetables, or salad, many people decide they don’t want it bad enough.[42]

|

Using the Half-Plate Rules works amazingly well at home, but only if you also use it when you shop. [43] To use it, you need to have enough fruits, vegetables, and salad around in the first place. If you think about you and your family being half-plate healthy as you shop you’ll buy healthier and you’ll also spend more. The first is good for you, the second is good for the store.[44]

Wegman’s jumped on the idea. Although stores aren’t too keen about sharing sales data, it must have been a huge hit with their employees. Within two years, it was rolled out to all their stores, and you can now get Half-Plate rule placemats, magnets, posters. (They renamed it the trademarkable Half-Plate Healthy.) You can see it in action in any of their stores, and the only place it works better than in a grocery store, is in your home Supermarkets don’t have to talk about servings of fruits and vegetable to get the point across. All they need to do was to reinforce the idea that half the plate could hold whatever fruit, vegetables, or salad a person wanted. They can do this on signs, specials, recipes, or in-store promotions—and subtly encourage people to fill their cart with lots more fruits and vegetables.[45] |

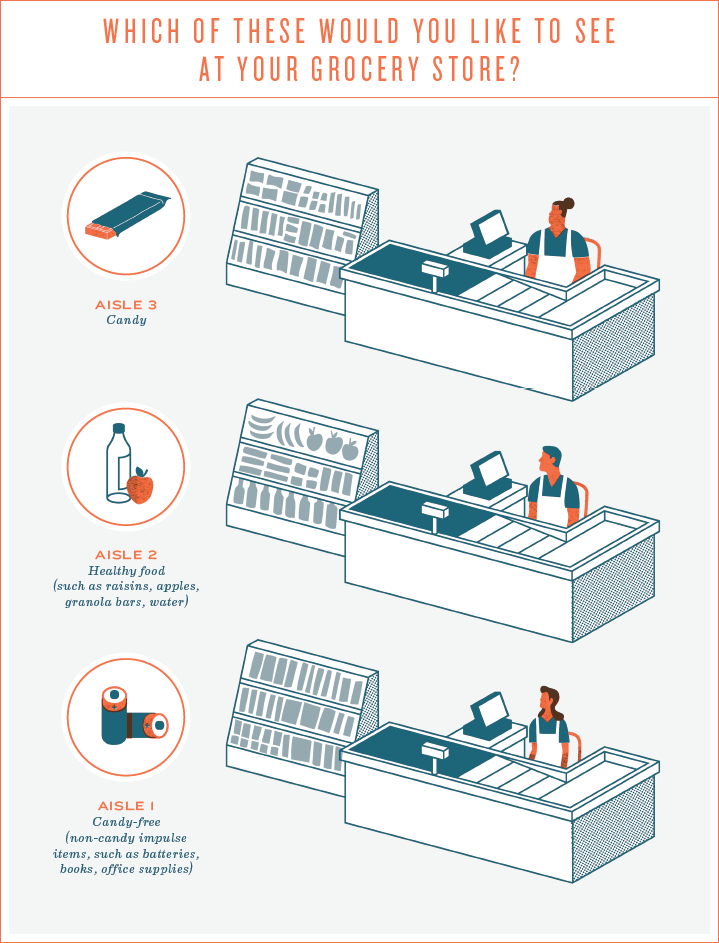

The Three Checkouts

Grocery shopping isn't exactly a trip to Fantasy Island, but the checkout line can be an exception. It’s filled with guilty-pleasure rewards at the end of the ho-hum errand of shopping. There are bizarre new gum flavors like mango chutney mint, meal-size candy bars, and irresistibly tacky tabloids with headlines like “Cellulite of the Stars.” They’re entertaining, but if you’re with kids, you’re doomed. Kids in grocery checkout lines are like kids in toy stores. They grab, bug, beg, pout, and scream. And if we cave in to buying pink marshmallow puff candy shaped like a Hello Kitty, we also cave into buying something with lots of chocolate – for us. There’s usually nothing in the aisle that we actually need, but after 45 minutes of seeing food, guess what we want? It’s not a snack-size can of lima beans. So we buy the Heath bar we swore we’d never buy again, finish it by the time we leave the parking lot, and shake our head on the way home . . . just as we did last week.

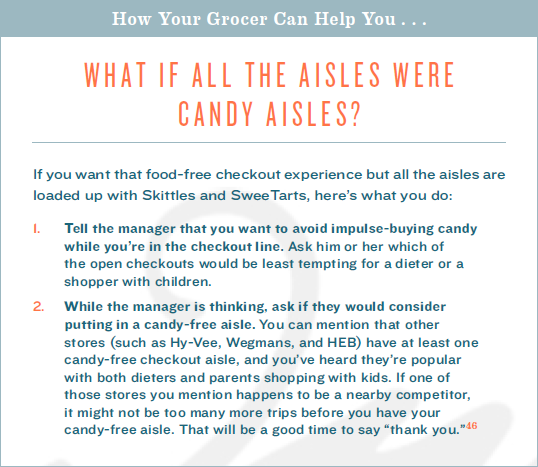

One supermarket solution is to set up at least one checkout line so it’s totally candy free.[47] Just as large supermarkets have different lines for “10 items or less” or “cash only,” some lines could have candy, others could have healthy snacks, and some could totally be free of food. The stores could still sell magazines and other crazy things--like eyeglass repair kits and Super Glue--but one or two aisles wouldn’t have any food at all.

To see what tired shoppers in grocery store parking lots thought of this idea, we asked, “If a grocery store had ten checkout lines, how many should be candy lines, healthy lines, or food-free lines?” here’s what we found:

• Men shopping alone wanted more of the candy lines.

• Women shopping alone wanted more of the healthy food lines.

• Mothers shopping with children wanted more food-free lines.

• Fathers shopping with children didn’t exist.

It might be an easier first step to help convince your local supermarket manager to start by adding a healthy line--perhaps selling fresh fruit, granola bars, and so on. It might be the one longer line shoppers wouldn’t mind waiting in. When the manager sees those lines getting longer, he’ll quickly make the bigger steps. If he doesn’t, there are other places you can shop.

One supermarket solution is to set up at least one checkout line so it’s totally candy free.[47] Just as large supermarkets have different lines for “10 items or less” or “cash only,” some lines could have candy, others could have healthy snacks, and some could totally be free of food. The stores could still sell magazines and other crazy things--like eyeglass repair kits and Super Glue--but one or two aisles wouldn’t have any food at all.

To see what tired shoppers in grocery store parking lots thought of this idea, we asked, “If a grocery store had ten checkout lines, how many should be candy lines, healthy lines, or food-free lines?” here’s what we found:

• Men shopping alone wanted more of the candy lines.

• Women shopping alone wanted more of the healthy food lines.

• Mothers shopping with children wanted more food-free lines.

• Fathers shopping with children didn’t exist.

It might be an easier first step to help convince your local supermarket manager to start by adding a healthy line--perhaps selling fresh fruit, granola bars, and so on. It might be the one longer line shoppers wouldn’t mind waiting in. When the manager sees those lines getting longer, he’ll quickly make the bigger steps. If he doesn’t, there are other places you can shop.

Back to Bornholm

After watching, coding, and analyzing shoppers on the Danish island of Bornholm, we generated a small list of changes--baby steps--these grocers could make to profitably help shoppers become slim by design. We were scheduled to present these ideas to all nine grocery store managers one night at the Bornholm Island Hall after they got off of work a couple days later at 7:30.

Unfortunately, two days later at 7:30 my five-person delegation of researchers almost equaled the six grocery managers who actually showed up. Strike one. After starting the presentation with the only Danish word I knew--“Velkommen” (welcome)--I told them the night was all about “New ways you can sell more of your healthier foods and make more money.” We then went on to give a punchy presentation on seven easy changes that we knew would work well. We had photos, video clips of shoppers, cool study results, numbers, and funny stories. It was great . . . except that nobody laughed, asked a question, moved, or even seemed to blink. It was like Q&A hour in a wax museum. Strike two.

Unfortunately, two days later at 7:30 my five-person delegation of researchers almost equaled the six grocery managers who actually showed up. Strike one. After starting the presentation with the only Danish word I knew--“Velkommen” (welcome)--I told them the night was all about “New ways you can sell more of your healthier foods and make more money.” We then went on to give a punchy presentation on seven easy changes that we knew would work well. We had photos, video clips of shoppers, cool study results, numbers, and funny stories. It was great . . . except that nobody laughed, asked a question, moved, or even seemed to blink. It was like Q&A hour in a wax museum. Strike two.

|

Because there were no signs of life, I idled down my enthusiasm and wrapped up our presentation a half hour early so my Danish colleagues could try to salvage the evening. Once they starting talking in Danish, some sort of switch flipped in the managers. They started talking louder, started to unDanishly interrupt each other, and then started arguing. Thinking things were getting out of control, I suggested we call it a night before they started to break furniture. My Danish colleagues waved me off and the melee continued. An hour later, things had slowed down, and the managers thanked us and cleared out. Before we started cleaning up, I asked my Danish colleagues why they were so irate. They said, “Oh, no. They like the changes and they’ll make most of them. The rest of the time they were talking about the otherchanges they wanted to make, like having more produce tastings, more pre-prepared salads, and bundling meet and vegetable specials together.”

After all our supermarket makeovers, does every Bornholmian look like a sleek, slim, Danish version of Mad Men? The early signs point in the right direction. One way to tell how well a new idea is working is by how many people want to jump in and be a part of it. The more changes we made to the grocery stores in Bornholm, the more other groups got involved. Before long, a public health advertising campaign was being rolled out, petitions were launched, and local ordinances were proposed. After the kitchen smoke clears, it will be difficult to see which of these moved the dial the most--but the people on the island are buying in to becoming slim by design. |

Yet these supermarket makeovers were cheap and easy to make. Many were done over a weekend, and we projected they would turn a profit within a month if not immediately. Still, if even one works, stores will be further ahead than before. It’s the beauty of being slim by design.

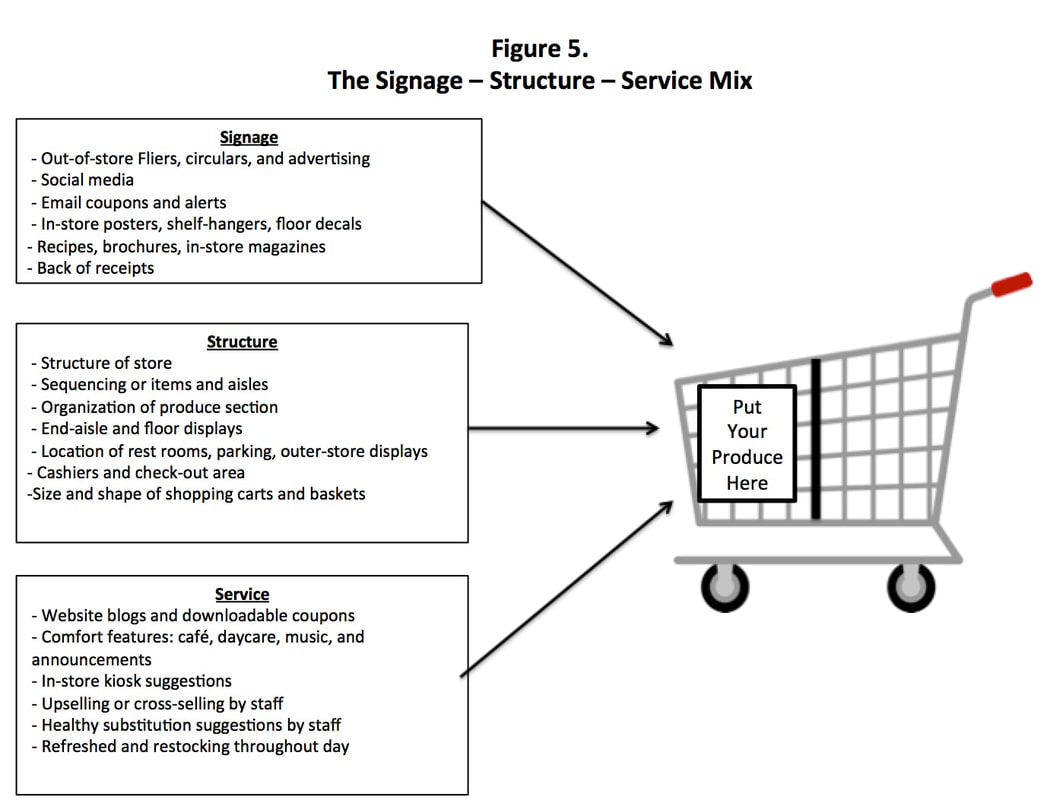

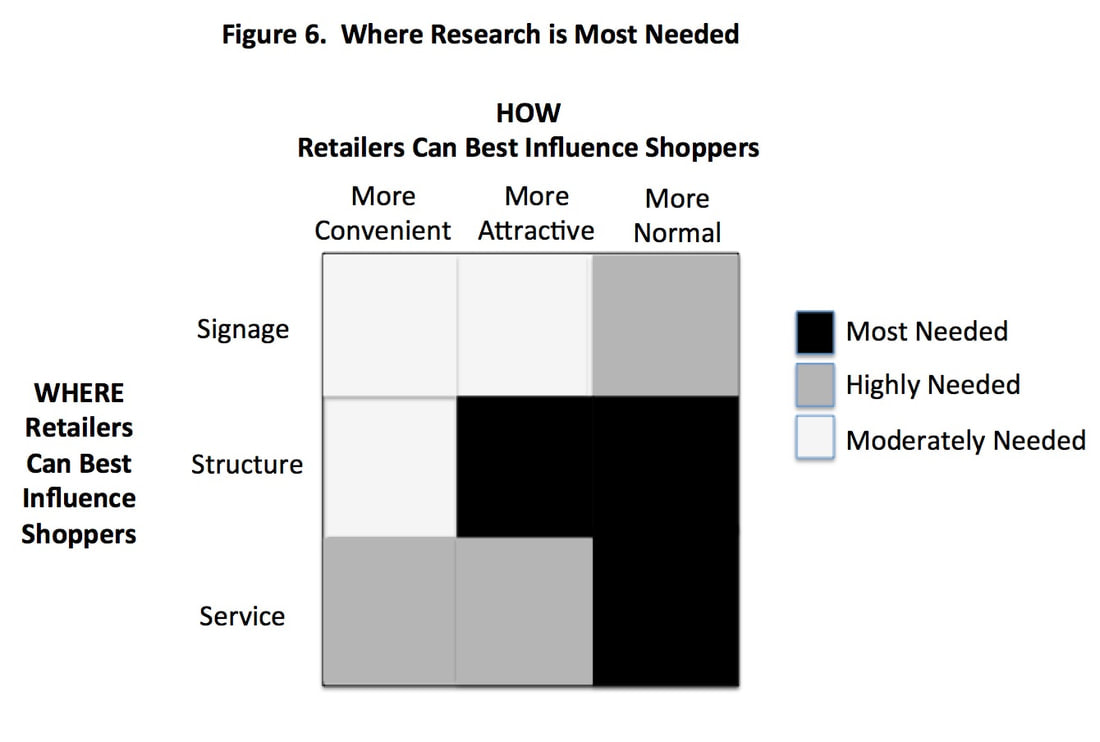

How Your Grocery Store Can Make You Slim

There are dozens of ways your favorite grocery story could help you shop a little healthier. A while back I shared the Bornholm story with some of the innovative grocery stores that sponsored some of the studies you’ve read about throughout this chapter. They all had clever ideas they were trying out in their stores to help their customers shop little healthier, but they were all doing something different--and often repeating each other’s mistakes. If we could pool together all of my Lab’s Slim by Design research findings with some of the ideas they were successfully experimenting with, we could make a Scorecard that could guide all grocery stores on all of the profitably, healthy changes they could make.

Grocery chains are competitive--and not just for shoppers. Even though a grocery chain in Texas doesn’t compete for the same shoppers as a grocery chain in Chicago, they all want to win awards for Most Popular, Prettiest, Smartest, or Most Likely to Succeed at their annual Grocery Store-a-Palooza Award Conference. Because having a Scorecard means there might be yet another new award they could compete on, most were all in to get started developing one. But more important than enabling grocery chains to compete with each other, this Scorecard will transparently show them exactly how to compete. Also, it will tell shoppers what they should look for or ask their local grocery store manager to do. If all these changes help grocery stores make a little more money, grocers would want to make the changes. If all these changes help shoppers shop a little healthier, shoppers would want to hassle their favorite grocer until he or she changed them.

Grocery chains are competitive--and not just for shoppers. Even though a grocery chain in Texas doesn’t compete for the same shoppers as a grocery chain in Chicago, they all want to win awards for Most Popular, Prettiest, Smartest, or Most Likely to Succeed at their annual Grocery Store-a-Palooza Award Conference. Because having a Scorecard means there might be yet another new award they could compete on, most were all in to get started developing one. But more important than enabling grocery chains to compete with each other, this Scorecard will transparently show them exactly how to compete. Also, it will tell shoppers what they should look for or ask their local grocery store manager to do. If all these changes help grocery stores make a little more money, grocers would want to make the changes. If all these changes help shoppers shop a little healthier, shoppers would want to hassle their favorite grocer until he or she changed them.

How Grocery Stores Can Profitably Help Us Shop Healthier . . .

Here's Why This WorksHere's why other grocery stores have made the move to make it easier for their loyal shoppers to eat healthier.

|

Here's How this WorksHere's the science behind "Healthy Profits" . . . and the scorecard to show how your stores are doing.

|

Healthier 7-Elevens?This program helped make your local convenience stores a little healthier. Fill 'er up and grab an apple.

| ||||||||||||||||||

Evidence-based Support and Published References

[1] The only remaining photo of the original Kleenex Cam is in this newspaper article below. By today’s tech standards, its pretty boring, but back then it was really souped up. Read about it at SlimByDesign.org/GroceryStores/.

[2] Again, all of these studies have been approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board. Each study planned by university researchers must be submitted to that university’s Institutional Review Board to ensure it will not harm the participants. Their identity is always protected, whatever they say and do is anonymous, and any record of their participation is eliminated once we analyze the data.

[3] One interesting category of items that are most likely to become cabinet castaways are unusual foods that people are buying for a specific occasion. When that occasion never happens, the food just sits and sits. This is neat article on that: Wansink, Brian, S. Adam Brasel, and Stephen Amjad (2000), “The Mystery of the Cabinet Castaway: Why We Buy Products We Never Use,” Journal of Family and Consumer Science, Vol. 92:1, 104-108.

[4] All of these studies are pre-approved. Today – compared to 20 or even 10 years ago – needs to be approved by a University’s Institutional Review Board to make sure that they are safe and to make sure all of the data is collected anonymously and that no one will ever know about that day you bought that EPT kit and the 2 pints of Chocolate Fudge Swirl. Some studies – like many shopping studies – are observational – but others might ask a person to complete a questionnaire at the end of a trip in exchange for a small amount of money, free food, movie tickets, and so on.

[5] That is, about 88 percent of this food will be eaten. The 12 percent that’s wasted, however, isn’t the candy, chips, and ice cream, it’s typically the spoiled fruit and vegetables, leftovers, and cabinet castaways. Brian Wansink (2001), “Abandoned Products and Consumer Waste: How Did That Get into the Pantry?” Choices, (October), 46.

[7] A cool example of all of these hidden cameras in use can be found at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2B0Ncy3Gz24. It’s not at a grocery store but in a lunchroom. Same approach.

[8] Lots of people visit our lab (even from way overseas), like its some weird trip to Consumer Mecca. Something I’ve heard a number of times is “Wow . . . this isn’t really very high tech!” No, it isn’t. What we’d like to think, however, is that insights trump glitzy technology every day of the week. We’ve got low-definition hidden cameras, hidden scales, counters, and timers, because we don’t need holograms or brain-scan machines to nail down the reality – not the theory – of why people do what they do. You don’t need infrared sensors to see someone eating twice as many Cheetos when you change what they’re watching on TV.

[9] Denmark actually has a number of little islands, but none like poor Bornholm. It never gets any peace. Strategically located in the Baltic Sea, it was occupied by the Germans during almost all of World War II and the Russians right after that. And probably by the Vikings way before that.

[10] People – whether public health professionals or politicians – can often can get very dramatic in what they tell grocery stores they should do. Dramatic, but not always realistic or right.

[11] This is an interesting paper of unintended consequences, Brian Wansink, Drew Hanks, David R. Just, John Cawley, Jeffrey Sobal, Elaine Wethington, William D. Schulze, and Harry M. Kaiser, 2012) “From Coke to Coors: A Field Study of a Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax and its Unintended Consequences (May 26, 2012). Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2079840 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2079840

[12] This is controversial for me to admit since I’m the immediate past-President of the Society for Nutrition Education and Behavior and because I was the White House-appointed person (2007-2009) in charge of promoting the Dietary Guidelines for the USDA.

[13] This was one focus of my book Mindless Eating. The basic idea is that making small changes around you that you don’t even really notice has a tremendous long term impact on changing behavior and weight.

[14] We no longer use the Kleenex Cam but we still call it that. We now use our bottles, hats, and iPhone videos.

[15] A number of years ago we gave secretaries dishes of chocolate kisses which we either placed on their desk or six feet from their desk. We found that those who had to walk only 6 feet, ate half as much candy (100 calories less; 4 each day instead of 9). Yet when we asked them if it’s because the 6-foot walk was too far or too much of a hassle, their answer surprised us. They said instead that the 6-foot distance gave them a chance to pause and ask themselves if they were really that hungry. Half the time they’d answer “no.” The key was that something – that distance – caused them to pause and interrupt their mindlessness: Brian Wansink, James E. Painter and Yeon-Kyung Lee (2006), “The Office Candy Dish: Proximity’s Influence on Estimated and Actual Candy Consumption,” International Journal of Obesity, 30:5 (May), 871-5.

[16] Anything that stops and makes a person pause – even for a split second – might be enough to knock themselves out of their mindless trance and rethink.

[17] The average grocery shopper buys only 24 percent fruits and vegetables. French, Simone, Melanie Wall, Nathan R. Mitchell, Scott T. Shimotsu, and Ericka Welsh (2009), “Annotated Receipts Capture Household Food Purchases From a Broad Range of Sources,” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 6, 37.

[18] Brian Wansink, C.R. Payne, K.C. Herbst, D. Soman (2013), “Part Carts: Assortment Allocation Cues that Increase Fruit and Vegetable Purchases,” Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 45:4S, 42.

[19] Brian Wansink, Dilip Soman, Kenneth C. Herbst, and Collin R. Payne (2012), “Partitioned Shopping Carts: Assortment Allocation Cues that Increase Fruit and Vegetable Purchases,” under review.

[20] A really robust finding. A great reason why you should also pass around the salad and green beans to your kids at dinner time before you bring out the lasanga – Brian Wansink and David Just (2011), “Healthy Foods First: Students Take the First Lunchroom Food 11% More Often Than the Third,” Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, Volume 43:4S1, S9.

[21] You can just believe me, or you can read ponderous evidence of why this happens: Chandon and Brian Wansink (2002), "When Are Stockpiled Products Consumed Faster? A Convenience--Salience Framework of Postpurchase Consumption Incidence and Quantity," Journal of Marketing Research, 39 (3), 321-35.

[22] This is a really neat finding, but it seems like it will take a miracle to get it published. In the meantime, you can find it on SSRN: Brian Wansink and Kate Stein 2013, “Eyes in the Aisle: Eye Scanning and Choice in Grocery Stores.

[23] Would this dashed green line work through the rest of the store? It could go down some of the healthier aisles – say canned fruits and vegetables or foods with whole grains – and around much of the perimeter of the store. Yet to use a quotation from the classic movie, This is Spinal Tap, “It’s a fine line between clever and stupid.” This line might work well in the produce section, but don’t take it overboard. It might be irritating or too strange in the rest of the store – particularly because these long aisles might make it look like a highway divider.

[24] My good colleagues Collin Payne and David Just have early evidence that this works well when it’s first laid out. See Collin R. Payne and David R. Just (2014) “Using Floor Decals and Way Finding to Increase the Sales of Fruits and Vegetables,” Forthcoming.

[25] See above “Eyes in the Aisle.”

[26] If you want a beleaguered researchers view of how this works, here’s a piece written for the New York Times Op-Ed page: Kate Stein (2009, “Shop Faster,” New York Times, April 15 p. A29.

[27] One source for this is Drew Hanks and Brian Wansink (2014), “Correlates of Purchase Quantities in Grocery Stores,” under review.

[28] Of course this is less accurate than measuring people barefoot with a German-made stadeometer, but knowing someone’s relative height is probably sufficient. Being able to document a 6’ male is taller than a 5’5” female is close enough for this calibration. This issue of precision does raise to mind the comedian Ron White’s quote, “I’m a pretty big guy – between 6’ and 6’6” – depending on what convenience store I’m coming out of.”

[29] In this study with Kate Stein, we tracked what people put in their carts but we didn’t track them to the cash register. Still, unless someone changes their mind when in the National Enquirer checkout line, we assume what they took, they probably bought.

[30] And 12 inches is even a stretch. Most purchased products were within a 6-inch range – higher or lower – of eye level for a particular shopper. This includes 37 percent of what women put in their cart and 44 percent for men. To stretch the range of products purchased even further, widen the shopping aisles. If an aisle is narrow – six feet or less – 61 percent of the products you buy will be within 12 inches of eye-level. But if you’re in a wider aisle, you look higher and lower. If it’s only two feet wider, half of what you buy will be outside this eye zone. But wide aisles also have something else going for them.

[31] Paco Underhill, (2000) Why We Buy: The Science of Shopping, Simon and Shuster: New York.

[32] There’s also an irritation factor with narrow aisles. If a person can’t see a clear way through an aisle, they might be less likely to go down it. And if you keep getting interrupted by people as you’re trying to shop because they’re scooting by you, you’re less likely to linger.

[33] See Brian Wansink and Kate Stein (2014) “Eye Height and Purchase Probability,” forthcoming.

[34] Here’s the best proof why you shouldn’t shop when you’re hungry: Brian Wansink, Aner Tal, Mitsuru Shimizu (2012), “First Foods Most: After 18-Hour Fast, People Drawn to Starches First and Vegetables Last,” Archives of Internal Medicine, 172:12 (June 25), 961-3.

[35] This is a current working paper by Brian Wansink and Drew Hanks “Timing, Hunger, and Increased Sales of Convenience Foods.” Hopefully, published in time for our retirement.

[36] One of the ways we’ve tested this is by intercepting grocery shoppers in the parking lot on their way into a store. We ask them to answer a couple of questions about the store and if we could talk to them after they shop. If they say yes, we tag their cart so we can catch them as they check out. At that time, we ask them a few questions about their experience and ask if can have a copy of their shopping receipt. A second group of people get the exact same treatment, except that they’re also given a piece of sugarless gum as a thank you. We tag their cart with a different color tag, and again catch them as they check out.

[37] This is a great study that shows that surprisingly shows that either taxing bad foods and subsidizing good foods seems to backfire. When you subsidize healthy foods, people buy more of both healthy and unhealthy foods. When you tax unhealthy foods, shoppers by less of both unhealthy and healthy foods. Here it is: “How Nutrition Rating Systems in Supermarkets Impact the Purchases of Healthy and Less Healthy Foods” by John Cawley, Matthew J. Sweeney, David R. Just, Harry M. Kaiser, William D. Schultze, Jeffery Sobal, Elaine Wethington, and Brian Wansink.

[38] This is an award-winning article which opened a lot of eyes with the Health Halo concept: Pierre Chandon and Brian Wansink (2007), "The Biasing Health Halos of Fast Food Restaurant Health Claims: Lower Calorie Estimates and Higher Side-Dish Consumption Intentions," Journal of Consumer Research, 34:3 (October) 301-314.

[39] There’s a ton of evidence here that’s compelling, but what too boring to talk about in the text. It happens with both low-fat foods and with foods with healthy names. Know yourself out reading these two boring (but award-winning papers): One’s mentioned in the prior footnote and the other one is Brian Wansink and Pierre Chandon (2006), “Can Low-Fat Nutrition Labels Lead to Obesity?” Obesity, 14 (September), A49-50.

[40] Wansink, Brian (2006), Mindless Eating – Why We Eat More Than We Think, New York: Bantam-Dell, p. 178-9+.

[41] Check out the article, Brian Wansink and Kathryn Hoy (2014) “Half-plate versus MyPlate: The Simpler the System, the Better the Nutrition,” working paper and Brian Wansink and Alyssa Niman (2012), "The Half-Plate Rule vs MyPlate vs Their Plate: The Effect on the Caloric Intake and Enjoyment of Dinner," Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 44:4 (July-August), S33

[42] The more latitude we give, the more likely they’ll follow our advice. When rules become just a little too complicated or vague, we find reasons to stop following them. This was an early problem with MyPlate. When somebody starts questioning “Where does my dessert go?” or “How am I supposed to eat fruit with dinner,” the more likely they are to simply say, “Whatever” and ignore it.

[43] A recap of this done by Jane Andrews, Wegman’s dietician, can be found at http://rochester. kidsoutandabout.com/node/1901 (downloaded 11-20-11)

[44] See more at Brian Wansink and Alyssa Niman (2012), "The Half-Plate Rule vs MyPlate vs Their Plate: The Effect on the Caloric Intake and Enjoyment of Dinner," Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 44:4 (July-August), S33.

[45] Learn more about how Wegmann’s implemented our idea at http://www.wegmans.com/webapp/wcs/stores/servlet/ProductDisplay?storeId=10052&partNumber=UNIVERSAL_20235

[46] Again, Brian Wansink and Kathryn Hoy (2014) “Half-plate versus MyPlate: The Simpler the System, the Better the Nutrition,” .

[2] Again, all of these studies have been approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board. Each study planned by university researchers must be submitted to that university’s Institutional Review Board to ensure it will not harm the participants. Their identity is always protected, whatever they say and do is anonymous, and any record of their participation is eliminated once we analyze the data.

[3] One interesting category of items that are most likely to become cabinet castaways are unusual foods that people are buying for a specific occasion. When that occasion never happens, the food just sits and sits. This is neat article on that: Wansink, Brian, S. Adam Brasel, and Stephen Amjad (2000), “The Mystery of the Cabinet Castaway: Why We Buy Products We Never Use,” Journal of Family and Consumer Science, Vol. 92:1, 104-108.

[4] All of these studies are pre-approved. Today – compared to 20 or even 10 years ago – needs to be approved by a University’s Institutional Review Board to make sure that they are safe and to make sure all of the data is collected anonymously and that no one will ever know about that day you bought that EPT kit and the 2 pints of Chocolate Fudge Swirl. Some studies – like many shopping studies – are observational – but others might ask a person to complete a questionnaire at the end of a trip in exchange for a small amount of money, free food, movie tickets, and so on.

[5] That is, about 88 percent of this food will be eaten. The 12 percent that’s wasted, however, isn’t the candy, chips, and ice cream, it’s typically the spoiled fruit and vegetables, leftovers, and cabinet castaways. Brian Wansink (2001), “Abandoned Products and Consumer Waste: How Did That Get into the Pantry?” Choices, (October), 46.

[7] A cool example of all of these hidden cameras in use can be found at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2B0Ncy3Gz24. It’s not at a grocery store but in a lunchroom. Same approach.

[8] Lots of people visit our lab (even from way overseas), like its some weird trip to Consumer Mecca. Something I’ve heard a number of times is “Wow . . . this isn’t really very high tech!” No, it isn’t. What we’d like to think, however, is that insights trump glitzy technology every day of the week. We’ve got low-definition hidden cameras, hidden scales, counters, and timers, because we don’t need holograms or brain-scan machines to nail down the reality – not the theory – of why people do what they do. You don’t need infrared sensors to see someone eating twice as many Cheetos when you change what they’re watching on TV.

[9] Denmark actually has a number of little islands, but none like poor Bornholm. It never gets any peace. Strategically located in the Baltic Sea, it was occupied by the Germans during almost all of World War II and the Russians right after that. And probably by the Vikings way before that.

[10] People – whether public health professionals or politicians – can often can get very dramatic in what they tell grocery stores they should do. Dramatic, but not always realistic or right.

[11] This is an interesting paper of unintended consequences, Brian Wansink, Drew Hanks, David R. Just, John Cawley, Jeffrey Sobal, Elaine Wethington, William D. Schulze, and Harry M. Kaiser, 2012) “From Coke to Coors: A Field Study of a Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax and its Unintended Consequences (May 26, 2012). Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2079840 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2079840

[12] This is controversial for me to admit since I’m the immediate past-President of the Society for Nutrition Education and Behavior and because I was the White House-appointed person (2007-2009) in charge of promoting the Dietary Guidelines for the USDA.

[13] This was one focus of my book Mindless Eating. The basic idea is that making small changes around you that you don’t even really notice has a tremendous long term impact on changing behavior and weight.

[14] We no longer use the Kleenex Cam but we still call it that. We now use our bottles, hats, and iPhone videos.

[15] A number of years ago we gave secretaries dishes of chocolate kisses which we either placed on their desk or six feet from their desk. We found that those who had to walk only 6 feet, ate half as much candy (100 calories less; 4 each day instead of 9). Yet when we asked them if it’s because the 6-foot walk was too far or too much of a hassle, their answer surprised us. They said instead that the 6-foot distance gave them a chance to pause and ask themselves if they were really that hungry. Half the time they’d answer “no.” The key was that something – that distance – caused them to pause and interrupt their mindlessness: Brian Wansink, James E. Painter and Yeon-Kyung Lee (2006), “The Office Candy Dish: Proximity’s Influence on Estimated and Actual Candy Consumption,” International Journal of Obesity, 30:5 (May), 871-5.

[16] Anything that stops and makes a person pause – even for a split second – might be enough to knock themselves out of their mindless trance and rethink.

[17] The average grocery shopper buys only 24 percent fruits and vegetables. French, Simone, Melanie Wall, Nathan R. Mitchell, Scott T. Shimotsu, and Ericka Welsh (2009), “Annotated Receipts Capture Household Food Purchases From a Broad Range of Sources,” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 6, 37.

[18] Brian Wansink, C.R. Payne, K.C. Herbst, D. Soman (2013), “Part Carts: Assortment Allocation Cues that Increase Fruit and Vegetable Purchases,” Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 45:4S, 42.

[19] Brian Wansink, Dilip Soman, Kenneth C. Herbst, and Collin R. Payne (2012), “Partitioned Shopping Carts: Assortment Allocation Cues that Increase Fruit and Vegetable Purchases,” under review.

[20] A really robust finding. A great reason why you should also pass around the salad and green beans to your kids at dinner time before you bring out the lasanga – Brian Wansink and David Just (2011), “Healthy Foods First: Students Take the First Lunchroom Food 11% More Often Than the Third,” Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, Volume 43:4S1, S9.

[21] You can just believe me, or you can read ponderous evidence of why this happens: Chandon and Brian Wansink (2002), "When Are Stockpiled Products Consumed Faster? A Convenience--Salience Framework of Postpurchase Consumption Incidence and Quantity," Journal of Marketing Research, 39 (3), 321-35.

[22] This is a really neat finding, but it seems like it will take a miracle to get it published. In the meantime, you can find it on SSRN: Brian Wansink and Kate Stein 2013, “Eyes in the Aisle: Eye Scanning and Choice in Grocery Stores.

[23] Would this dashed green line work through the rest of the store? It could go down some of the healthier aisles – say canned fruits and vegetables or foods with whole grains – and around much of the perimeter of the store. Yet to use a quotation from the classic movie, This is Spinal Tap, “It’s a fine line between clever and stupid.” This line might work well in the produce section, but don’t take it overboard. It might be irritating or too strange in the rest of the store – particularly because these long aisles might make it look like a highway divider.

[24] My good colleagues Collin Payne and David Just have early evidence that this works well when it’s first laid out. See Collin R. Payne and David R. Just (2014) “Using Floor Decals and Way Finding to Increase the Sales of Fruits and Vegetables,” Forthcoming.

[25] See above “Eyes in the Aisle.”

[26] If you want a beleaguered researchers view of how this works, here’s a piece written for the New York Times Op-Ed page: Kate Stein (2009, “Shop Faster,” New York Times, April 15 p. A29.

[27] One source for this is Drew Hanks and Brian Wansink (2014), “Correlates of Purchase Quantities in Grocery Stores,” under review.

[28] Of course this is less accurate than measuring people barefoot with a German-made stadeometer, but knowing someone’s relative height is probably sufficient. Being able to document a 6’ male is taller than a 5’5” female is close enough for this calibration. This issue of precision does raise to mind the comedian Ron White’s quote, “I’m a pretty big guy – between 6’ and 6’6” – depending on what convenience store I’m coming out of.”

[29] In this study with Kate Stein, we tracked what people put in their carts but we didn’t track them to the cash register. Still, unless someone changes their mind when in the National Enquirer checkout line, we assume what they took, they probably bought.

[30] And 12 inches is even a stretch. Most purchased products were within a 6-inch range – higher or lower – of eye level for a particular shopper. This includes 37 percent of what women put in their cart and 44 percent for men. To stretch the range of products purchased even further, widen the shopping aisles. If an aisle is narrow – six feet or less – 61 percent of the products you buy will be within 12 inches of eye-level. But if you’re in a wider aisle, you look higher and lower. If it’s only two feet wider, half of what you buy will be outside this eye zone. But wide aisles also have something else going for them.

[31] Paco Underhill, (2000) Why We Buy: The Science of Shopping, Simon and Shuster: New York.

[32] There’s also an irritation factor with narrow aisles. If a person can’t see a clear way through an aisle, they might be less likely to go down it. And if you keep getting interrupted by people as you’re trying to shop because they’re scooting by you, you’re less likely to linger.

[33] See Brian Wansink and Kate Stein (2014) “Eye Height and Purchase Probability,” forthcoming.

[34] Here’s the best proof why you shouldn’t shop when you’re hungry: Brian Wansink, Aner Tal, Mitsuru Shimizu (2012), “First Foods Most: After 18-Hour Fast, People Drawn to Starches First and Vegetables Last,” Archives of Internal Medicine, 172:12 (June 25), 961-3.

[35] This is a current working paper by Brian Wansink and Drew Hanks “Timing, Hunger, and Increased Sales of Convenience Foods.” Hopefully, published in time for our retirement.

[36] One of the ways we’ve tested this is by intercepting grocery shoppers in the parking lot on their way into a store. We ask them to answer a couple of questions about the store and if we could talk to them after they shop. If they say yes, we tag their cart so we can catch them as they check out. At that time, we ask them a few questions about their experience and ask if can have a copy of their shopping receipt. A second group of people get the exact same treatment, except that they’re also given a piece of sugarless gum as a thank you. We tag their cart with a different color tag, and again catch them as they check out.

[37] This is a great study that shows that surprisingly shows that either taxing bad foods and subsidizing good foods seems to backfire. When you subsidize healthy foods, people buy more of both healthy and unhealthy foods. When you tax unhealthy foods, shoppers by less of both unhealthy and healthy foods. Here it is: “How Nutrition Rating Systems in Supermarkets Impact the Purchases of Healthy and Less Healthy Foods” by John Cawley, Matthew J. Sweeney, David R. Just, Harry M. Kaiser, William D. Schultze, Jeffery Sobal, Elaine Wethington, and Brian Wansink.

[38] This is an award-winning article which opened a lot of eyes with the Health Halo concept: Pierre Chandon and Brian Wansink (2007), "The Biasing Health Halos of Fast Food Restaurant Health Claims: Lower Calorie Estimates and Higher Side-Dish Consumption Intentions," Journal of Consumer Research, 34:3 (October) 301-314.

[39] There’s a ton of evidence here that’s compelling, but what too boring to talk about in the text. It happens with both low-fat foods and with foods with healthy names. Know yourself out reading these two boring (but award-winning papers): One’s mentioned in the prior footnote and the other one is Brian Wansink and Pierre Chandon (2006), “Can Low-Fat Nutrition Labels Lead to Obesity?” Obesity, 14 (September), A49-50.

[40] Wansink, Brian (2006), Mindless Eating – Why We Eat More Than We Think, New York: Bantam-Dell, p. 178-9+.

[41] Check out the article, Brian Wansink and Kathryn Hoy (2014) “Half-plate versus MyPlate: The Simpler the System, the Better the Nutrition,” working paper and Brian Wansink and Alyssa Niman (2012), "The Half-Plate Rule vs MyPlate vs Their Plate: The Effect on the Caloric Intake and Enjoyment of Dinner," Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 44:4 (July-August), S33

[42] The more latitude we give, the more likely they’ll follow our advice. When rules become just a little too complicated or vague, we find reasons to stop following them. This was an early problem with MyPlate. When somebody starts questioning “Where does my dessert go?” or “How am I supposed to eat fruit with dinner,” the more likely they are to simply say, “Whatever” and ignore it.

[43] A recap of this done by Jane Andrews, Wegman’s dietician, can be found at http://rochester. kidsoutandabout.com/node/1901 (downloaded 11-20-11)

[44] See more at Brian Wansink and Alyssa Niman (2012), "The Half-Plate Rule vs MyPlate vs Their Plate: The Effect on the Caloric Intake and Enjoyment of Dinner," Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 44:4 (July-August), S33.

[45] Learn more about how Wegmann’s implemented our idea at http://www.wegmans.com/webapp/wcs/stores/servlet/ProductDisplay?storeId=10052&partNumber=UNIVERSAL_20235

[46] Again, Brian Wansink and Kathryn Hoy (2014) “Half-plate versus MyPlate: The Simpler the System, the Better the Nutrition,” .