Your job can make you fat, but it can also help make you healthier. Unfortunately, many wellness plans are like our own NewYear’s resolutions: They’re enthusiastic and bold, but they fizzle out.

You can see below how easy it is for your workplace to become healthier by design and how your company can help.

You can see below how easy it is for your workplace to become healthier by design and how your company can help.

Some FAQs About Workplace Wellness

|

How can my company make the break room healthier?

How can my company make the office cafeteria healthier?

How can I better avoid the office vending machine? Do company health clubs and fitness competitions work?

What is a Company Health Code and should I sign it?

Will I lose weight if I bring my lunch to work?

Do I gain weight if I eat at my desk at work?

What management incentives make employees healthier?

What wellness program makes employees healthier?

|

How could my job make me healthier? |

Small changes that gave Google an edge |

Tell them how to help |

|

Here's a few examples of how some companies have made it easier for employees to be healthier.

The scorecard in the back shows if your company is making you healthier or not.

|

Here's a video of how some simple changes made a quick improvement in Google's free-food cafeterias and micro-kitchen breakrooms.

|

Here are some ideas your company can use to help you and your coworkers become healthier and happier.

Edit this and pass it along to your boss, HR manager, or health and wellness director.

| ||||||||||||

Fat-Proofing Your Office Space and Workplace

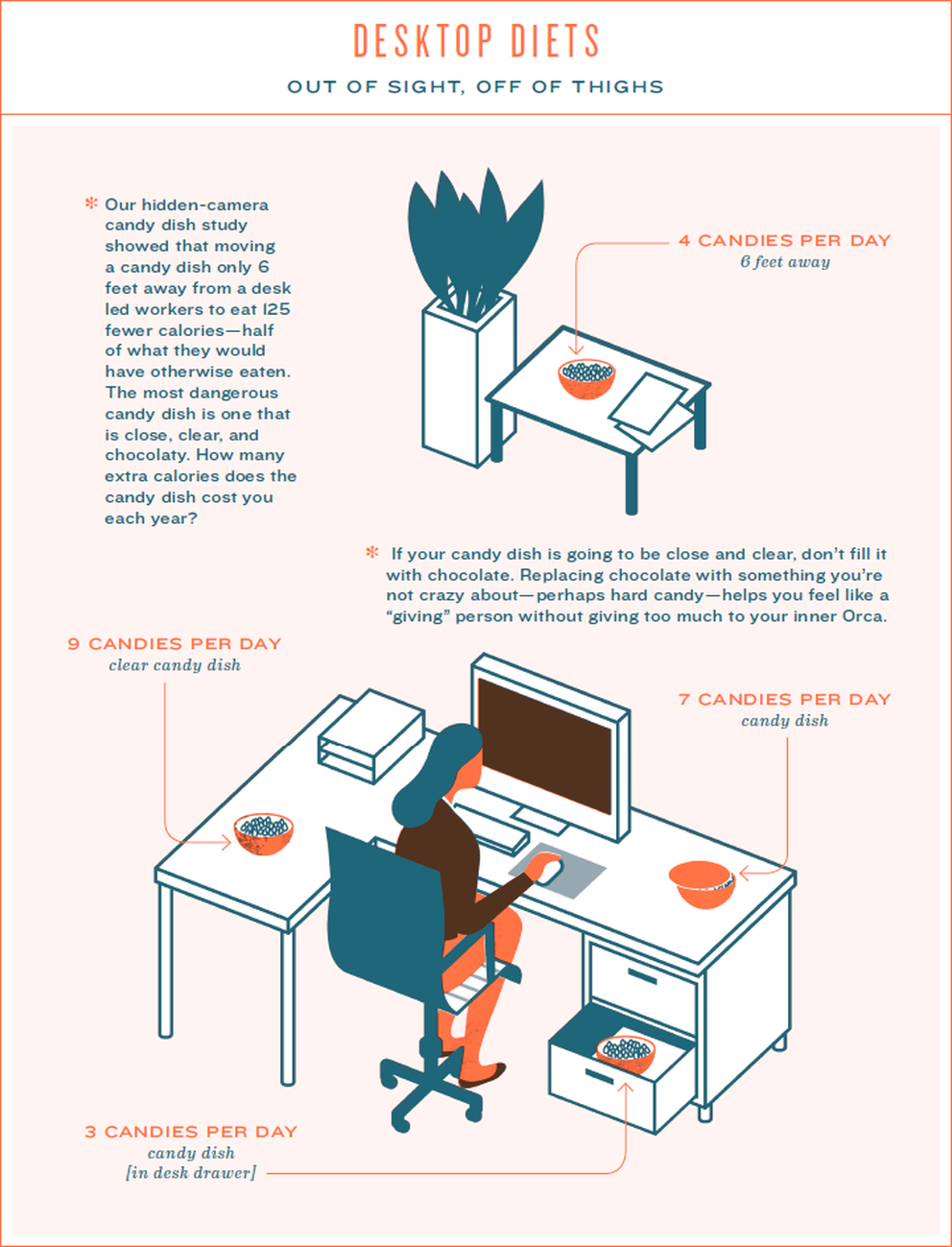

Lots of us squirrel away food in our desks. If there’s ever an emergency need to hibernate in our office for the winter, we want to be prepared.

Just for fun, we conducted a snack-food desk audit of 122 office workers to see how well stocked the average desk is. People would pull out granola bars, gum, a half-full container of Tic-Tacs, ketchup packets, and errant M&Ms mingled in with the paper clips. The average office worker had 476 calories worth of food in their desk within arm’s reach.[1] One person had more than 3000 calories--bags of Cheetos, O Henry candy bars, wasabi packets, an opened granola bar in a zip-top bag, sugar-free Certs, and five cans of pop-top tuna fish. Three thousand calories and sugar-free Certs?[2] Perhaps for the tuna fish. Another desk had packets of Northwest Airlines peanuts, two warm beers, and a piece of birthday cake. Nothing gets you over a late morning carbo-craving like stale birthday cake and a warm beer.

Just for fun, we conducted a snack-food desk audit of 122 office workers to see how well stocked the average desk is. People would pull out granola bars, gum, a half-full container of Tic-Tacs, ketchup packets, and errant M&Ms mingled in with the paper clips. The average office worker had 476 calories worth of food in their desk within arm’s reach.[1] One person had more than 3000 calories--bags of Cheetos, O Henry candy bars, wasabi packets, an opened granola bar in a zip-top bag, sugar-free Certs, and five cans of pop-top tuna fish. Three thousand calories and sugar-free Certs?[2] Perhaps for the tuna fish. Another desk had packets of Northwest Airlines peanuts, two warm beers, and a piece of birthday cake. Nothing gets you over a late morning carbo-craving like stale birthday cake and a warm beer.

Move Away from the Desk

But, how harmful can eating a few calories at you desk really be? One thing we know is that people who had candy in or on their desk reported weighing 15.4 pounds more than those who didn’t. A 45-minute lunchtime workout can be undone in three minutes by an O Henry bar and vintage airline peanuts.

Yet while most people snack at their desk, there are others who eat their whole lunch there. We usually tell ourselves that we work through our lunches because we’re overwhelmed with work, we need to catch up on email, and we want that gold star for being a worker-bee. Sure, we might be overwhelmed, but it might also be an excuse. Eating at our desk is more convenient than dining at the cafeteria or wandering down the street to grab a sandwich, and it’s easier than asking someone to join us.

A nice solution would be if our company offered us something more interesting to do during lunch than update our Facebook page and watch YouTube videos of skateboarding dogs. Companies could offer a brown bag presentation series, a Pilates class, a made-over break room that doesn’t look like an air raid shelter from the Cold War, or even a lunchroom that offers foods in colors other than white and brown. These would be the first steps in a new kind of corporate wellness program: one that gets us to move a little more and eat a little better without really trying. One that’s focused on the majority of us who are already in pretty decent shape.

But, how harmful can eating a few calories at you desk really be? One thing we know is that people who had candy in or on their desk reported weighing 15.4 pounds more than those who didn’t. A 45-minute lunchtime workout can be undone in three minutes by an O Henry bar and vintage airline peanuts.

Yet while most people snack at their desk, there are others who eat their whole lunch there. We usually tell ourselves that we work through our lunches because we’re overwhelmed with work, we need to catch up on email, and we want that gold star for being a worker-bee. Sure, we might be overwhelmed, but it might also be an excuse. Eating at our desk is more convenient than dining at the cafeteria or wandering down the street to grab a sandwich, and it’s easier than asking someone to join us.

A nice solution would be if our company offered us something more interesting to do during lunch than update our Facebook page and watch YouTube videos of skateboarding dogs. Companies could offer a brown bag presentation series, a Pilates class, a made-over break room that doesn’t look like an air raid shelter from the Cold War, or even a lunchroom that offers foods in colors other than white and brown. These would be the first steps in a new kind of corporate wellness program: one that gets us to move a little more and eat a little better without really trying. One that’s focused on the majority of us who are already in pretty decent shape.

Rethinking Corporate Wellness

Not that long ago, companies used to pay workers to smoke. Everyone was given 15-minute breaks in the morning and again in the afternoon to have their coffee and cigarette.[3] Your company basically paid you 6.25 percent of your salary to go out and smoke a filter-less Camel if you wanted.

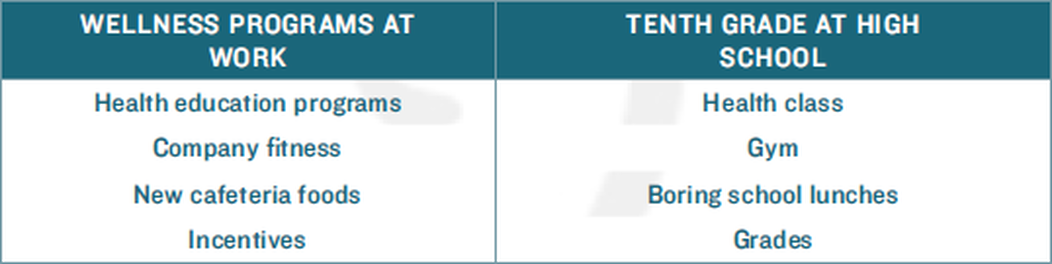

Today, company wellness is a big business--your company wants you to be healthy and productive, and the right wellness program can cut health care costs and absenteeism by 25 to 30 percent.[4] But many wellness plans seem more like our own New Year’s resolutions: They’re enthusiastic and bold, but the never really seem to deliver. These plans almost always have four parts: a health education program, a company fitness component, revamped cafeteria food, and incentives.[5] But unfortunately there just aren’t as many amazing success stories as there are disappointing fizzles.[6]

Part of the reason these plans don’t work is that they look suspiciously like tenth grade. Health education is like health class, company fitness is like gym, new cafeteria foods are like boring school lunches, and incentives are like grades. These programs might perk up the former valedictorian, but they don’t do too much for those of us who daydreamed our way through biology class.

Today, company wellness is a big business--your company wants you to be healthy and productive, and the right wellness program can cut health care costs and absenteeism by 25 to 30 percent.[4] But many wellness plans seem more like our own New Year’s resolutions: They’re enthusiastic and bold, but the never really seem to deliver. These plans almost always have four parts: a health education program, a company fitness component, revamped cafeteria food, and incentives.[5] But unfortunately there just aren’t as many amazing success stories as there are disappointing fizzles.[6]

Part of the reason these plans don’t work is that they look suspiciously like tenth grade. Health education is like health class, company fitness is like gym, new cafeteria foods are like boring school lunches, and incentives are like grades. These programs might perk up the former valedictorian, but they don’t do too much for those of us who daydreamed our way through biology class.

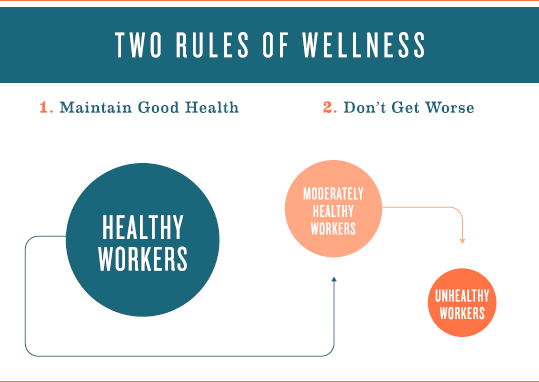

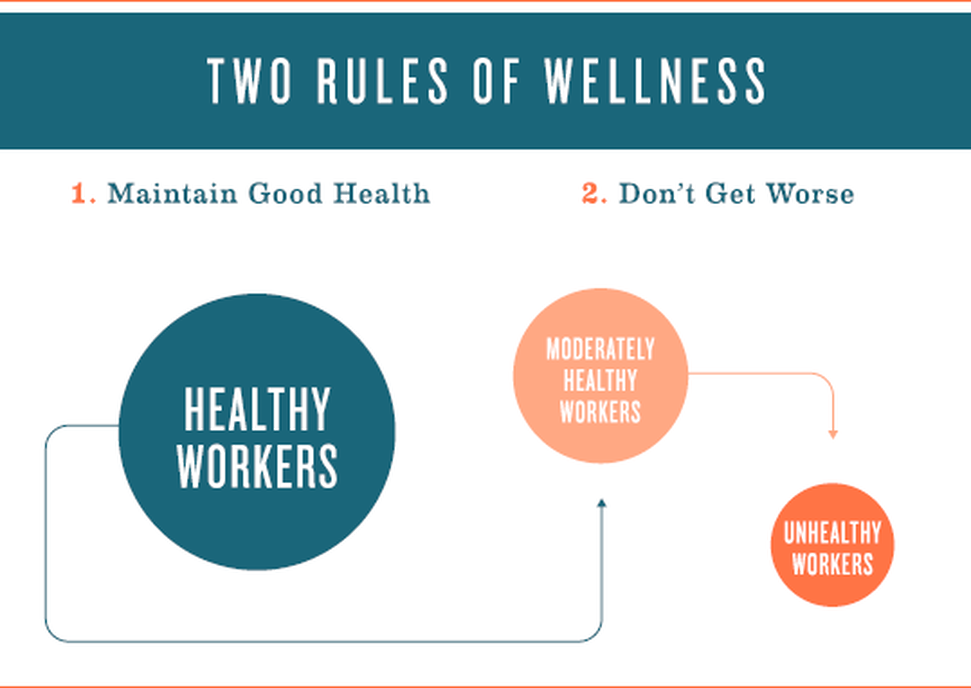

The companies we work with say that about 60 percent of their employees are healthy, another 30 percent are fairly healthy, and it’s the last 10 percent cost that cost all the money—through absenteeism, presenteeism (being at work without really working), and higher insurance costs.[7] Ten percent might not sound like a big deal, but there’s a migration: Healthy people gradually become fairly healthy, fairly healthy people gradually become unhealthy, and unhealthy people gradually leave the company. This seldom works in reverse.

Instead of focusing so much attention on the unhealthy people, it would be more forward-thinking to focus on keeping the healthy people healthy. You’ll never have everyone in perfect health, but as Dee Edington, a noted University of Michigan kinesiologist, argues, 1) Keep the healthy healthy and 2) Don’t let anyone get worse.

Instead of focusing so much attention on the unhealthy people, it would be more forward-thinking to focus on keeping the healthy people healthy. You’ll never have everyone in perfect health, but as Dee Edington, a noted University of Michigan kinesiologist, argues, 1) Keep the healthy healthy and 2) Don’t let anyone get worse.

But if corporate wellness programs are too much like going to school – health class, gym, lunchtime, and grades--they won’t work very well, because most people don’t want to be in school for the rest of their lives. Instead, the best wellness programs are ones people don’t even know they’re doing. Better to have a small program that helps most people than a glitzy one that helps only the Body for Life fanatics who were pumping it up anyway. Let’s start off easy with break room and cafeteria makeovers, then move to fitness and weight loss programs. After that we’ll get really radical.

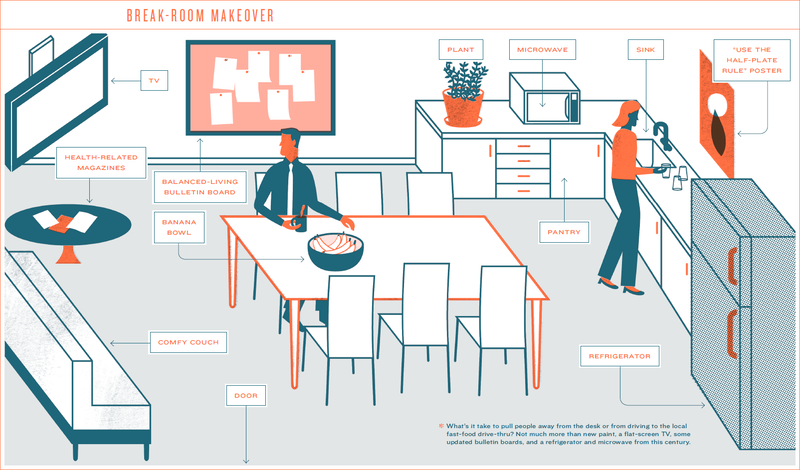

Break Room Makeovers

When people eat at their desks, it looks like they’re shackled to the oars of a galley ship. One advantage to break rooms or lunchrooms is they do just that: They give you a chance to enjoy a break and your lunch--if they’re done right.

Unfortunately, most break rooms don’t have that cozy Martha Stewart feel with the yellow, soft focus lighting. Instead, they look like the interrogation rooms you see in police movies--gray and barren with a beat-up metal table, glaring lights, and a Nick Nolte-looking guy who’s growling that “you can either do it the easy way or the hard way.” Of course this is an exaggeration. Unlike the interrogation room, your company break room has a Pepsi machine.

The Dutch have a word for warm, cozy places: “gezelig.” The Russians have a word for cold, non-cozy places: gulags. Most break rooms are less Dutch geszelig-y than they are Russian gulag-y. It’s no wonder they’re often empty and that people would rather sit at their desk updating their Facebook page than chatting with Mr. Nolte about the kids.

Unfortunately, most break rooms don’t have that cozy Martha Stewart feel with the yellow, soft focus lighting. Instead, they look like the interrogation rooms you see in police movies--gray and barren with a beat-up metal table, glaring lights, and a Nick Nolte-looking guy who’s growling that “you can either do it the easy way or the hard way.” Of course this is an exaggeration. Unlike the interrogation room, your company break room has a Pepsi machine.

The Dutch have a word for warm, cozy places: “gezelig.” The Russians have a word for cold, non-cozy places: gulags. Most break rooms are less Dutch geszelig-y than they are Russian gulag-y. It’s no wonder they’re often empty and that people would rather sit at their desk updating their Facebook page than chatting with Mr. Nolte about the kids.

As part of a slim by design redesign, we worked with a mid-size welding company that made a lot of large, iron, green-painted farm equipment parts. Their workers didn’t work at desks; they did real work--they moved, welded, lifted, and painted stuff. They went home with backaches, not headaches. But they also went home overweight.

The company had three shifts and no cafeteria. What they had was more along the line of a break room-lunchroom with a rusty refrigerator from an Animal House basement, a microwave with brown stains from burrito explosions, a couple work safety signs that said things like 4 days without an accident, and a beat-up table with dented folding chairs that had been used in fights. Outside the room there were four or five vending machines, including one of those 1950s-looking “Vend-o-Mat” machines where you spin the shelves around, plug in some money, and open a little door to take out your hermetically sealed egg-salad sandwich with no expiration date.

This wasn’t a place where people ate lunch at their desks—there were no desks. But the lunchroom was simply too depressing to entice any workers to eat there. Instead they would drive down to the local fast food restaurants or grab things out of the Vend-o-Mat and head out of the building to wolf it down and smoke. Who could blame them? No one wants to eat in an interrogation room.

We first focused on vending machines. We recommended that they move the Pepsi and candy machines to faraway corners on the factory floor. This way we weren’t taking away any indulgences, we were just making people work a little harder for them--they would have to walk another hundred yards for their Pepsi. We also asked Mr. Vend-o-Mat if he could add a few healthier foods--turkey and cheese, mixed nuts, fruit--and put these healthy foods in the eye-level slots. Since he made higher margins from these foods anyway, he did it immediately.

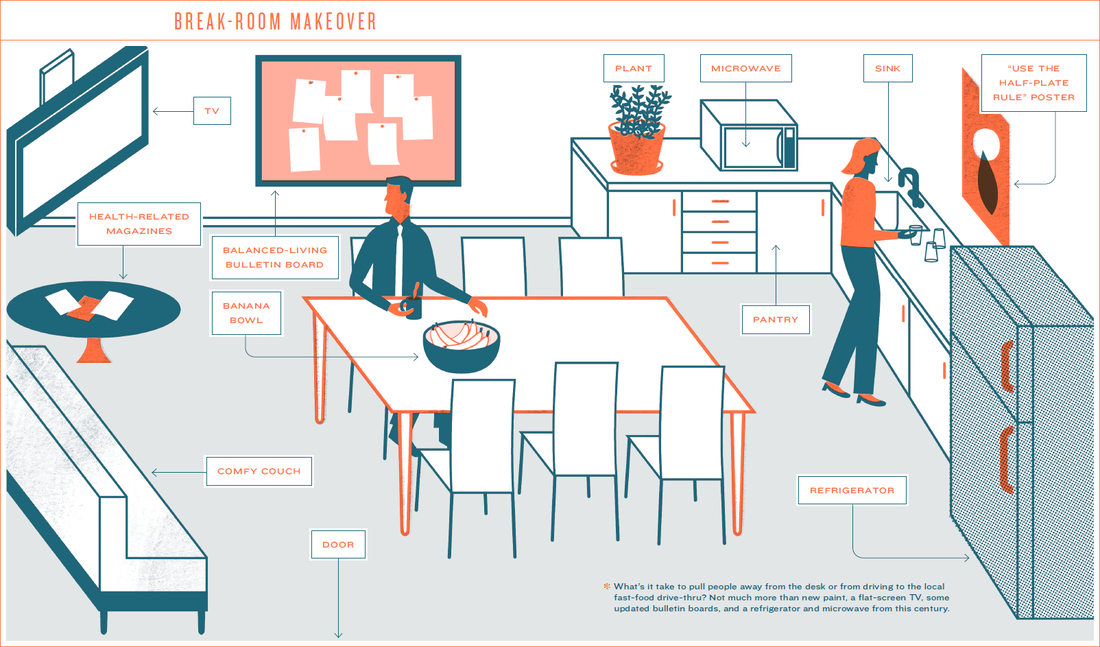

The second change was a break room makeover. Management brought in bright paint, nice lights, new appliances, tables, chairs, and a big flat-screen TV. They also put in some snappy posters,[9] an announcement bulletin board, and pamphlet holders with company newsletters and wellness brochures. Oh . . . and free fruit. Every day the company bought in bunches of bananas and put them in colorful bowls in the middle of each table. Inexpensive bananas that were great for the company and great for the workers.

Within one month, the lunchroom was the hip place to be. The TV set helped a lot, but so did the paint, posters, and free bananas. Workers spent less time driving to the drive-thru and picked up more health newsletters and brochures. The Mr. Pepsi distributor might have made a bit less coin because some people thought the new vending machine location was a little far to walk to, but he still got to keep a profitable account.

But doing a break room makeover isn’t just for the blue-collar factory floor. It’s also for office buildings. Making the break room a place to take a healthier break isn’t that expensive. And if workers don’t want to eat here, we might still get a shot at them in the cafeteria. Just be careful not to overdo it.

The company had three shifts and no cafeteria. What they had was more along the line of a break room-lunchroom with a rusty refrigerator from an Animal House basement, a microwave with brown stains from burrito explosions, a couple work safety signs that said things like 4 days without an accident, and a beat-up table with dented folding chairs that had been used in fights. Outside the room there were four or five vending machines, including one of those 1950s-looking “Vend-o-Mat” machines where you spin the shelves around, plug in some money, and open a little door to take out your hermetically sealed egg-salad sandwich with no expiration date.

This wasn’t a place where people ate lunch at their desks—there were no desks. But the lunchroom was simply too depressing to entice any workers to eat there. Instead they would drive down to the local fast food restaurants or grab things out of the Vend-o-Mat and head out of the building to wolf it down and smoke. Who could blame them? No one wants to eat in an interrogation room.

We first focused on vending machines. We recommended that they move the Pepsi and candy machines to faraway corners on the factory floor. This way we weren’t taking away any indulgences, we were just making people work a little harder for them--they would have to walk another hundred yards for their Pepsi. We also asked Mr. Vend-o-Mat if he could add a few healthier foods--turkey and cheese, mixed nuts, fruit--and put these healthy foods in the eye-level slots. Since he made higher margins from these foods anyway, he did it immediately.

The second change was a break room makeover. Management brought in bright paint, nice lights, new appliances, tables, chairs, and a big flat-screen TV. They also put in some snappy posters,[9] an announcement bulletin board, and pamphlet holders with company newsletters and wellness brochures. Oh . . . and free fruit. Every day the company bought in bunches of bananas and put them in colorful bowls in the middle of each table. Inexpensive bananas that were great for the company and great for the workers.

Within one month, the lunchroom was the hip place to be. The TV set helped a lot, but so did the paint, posters, and free bananas. Workers spent less time driving to the drive-thru and picked up more health newsletters and brochures. The Mr. Pepsi distributor might have made a bit less coin because some people thought the new vending machine location was a little far to walk to, but he still got to keep a profitable account.

But doing a break room makeover isn’t just for the blue-collar factory floor. It’s also for office buildings. Making the break room a place to take a healthier break isn’t that expensive. And if workers don’t want to eat here, we might still get a shot at them in the cafeteria. Just be careful not to overdo it.

Making Google Cafeterias Healthier

Some companies use food as a competitive weapon. Take Google. Since opening its binary doors in 1999, it’s had the policy of offering free food for all the brainiacs who work there. When Google decided to make food free, they did it big. First, they installed more than 130 free mini-7-Eleven snack rooms they call “micro-kitchens” that they pride on being within 100 feet of every single employee. These have all the snacks, cold drinks, coffees, and fruits you can imagine, and they say the average Googler is never move than one hundred feet away from food. It’s all free, free, and free. Before work, during work, and after work (but don’t take it home).

Second, they have amazingly super cool cafeterias that serve almost anything you would imagine (sushi, BBQ, curry, burgers, chili, Jell-O, dessert bars) and some foods you wouldn’t imagine (kale and pumpkin pizza). Grab a tray and pile it high. Go back for seconds if you wish. Repeat until you feel like your stomach is about to explode. And again, it’s all free, all the time. Management isn’t shy about saying why:[10]

• It’s a recruiting and retention plus.

• It keeps high-salaried software engineers on site rather than driving around for an hour looking for restaurant.

• It encourages good “accidental conversations” with other Googlers.

• It reduces bad “accidental conversations”--those involving trade secrets--with pesky neighborhood competitors.

Unfortunately, there’s also something called the “Google fifteen.” It’s the fifteen pounds new Googlers--they’re called Nooglers--are rumored to gain shortly after joining the clan. This isn’t unique to Google. There’s also the M&M/Mars fifteen and the Nabisco fifteen that happen at other headquarters. In fact, this probably happens at any company where there’s lots of tasty, widely available free food.

Some of the first steps to make the Micro Kitchens more slim by design were pretty straightforward. Armed with our cafeteria research findings (described in the next chapter), a student whose dissertation committee I was on, Jessica Wisdom, took a job with Google in People Analytics and started nudging things around.[11] We knew that the three things that determine what a person eats in a free food environment: 1) what’s most convenient, 2) what’s most attractive, and 3) what’s most normal.[12] So here’s what was done:

• All the healthy snacks--like fruits, baked things, and granola-ly things--were put on the top shelves and the less healthy snacks--like Kit-Kats and Peanut M&Ms--were reduced to the smaller “Fun Size” and put on the “I-can barely-see-it-from-here” bottom row.

• All the bottled waters and calorie-free flavored waters were put at eye level in the coolers and soft drinks at the bottom--water intake increased by 47 percent and drink calories dropped by 7 percent.

• Fruit bowls are now about the first and last thing you see.

• Candy is in opaque bins and not out in plain sight--9 percent less candy was taken in just the first week. [13]

The challenge with the Google Fifteen was to also figure out what to do about the massively tempting cafeterias. Our interviews with Googlers showed four complaints. Too much tasty variety led them to overeat, they wasted all sorts of food, they thought this was irresponsible and unsustainable, and they gained weight before they knew it – they had gained a Google Gut faster than they could say “The square root of 170 is 13.038.” Some small changes we recommended include:

• Putting the salad at the front of the line and the dessert at the back.

• Offering small plates to diners so they would take less--32 percent chose the smaller ones.[14]

• Downscaling the size of desserts to just three bites. They could still take a second or third helping, but not many do.[15]

One approach would be to reduce the variety of food. Sure, if Google only offered beans and rice, people won’t overeat . . . there. They’ll go off-campus to overeat--bad news. A better solution would be to make it less easy--but not impossible--to pile a four-foot stack of food on a tray. This could first be done by breaking that massive cafeteria into four smaller cafes based on the style of food--Asian, Vegetarian, Italian, and an American Grill. You could still pile on a four-foot stack of food; but you’d have to go in and out of four different doors--probably too much of a hassle for most people most of the time. Analogous to the 100-calorie pack, each time they left one of the four cafes, they’d have to ask themselves if they really wanted to visit the next one. They couldn’t blame Google for restricting their choices, they’d just think, Uhh . . . this is enough.

As for the complaints about irresponsibility and unsustainability, Google had a stoplight rating system for certain foods. Green was healthy, red was less healthy, and yellow was in-between. [16] Most people seemed to ignore it, so here’s what we suggested. Since every Googler has an ID card, they could have a debit account linked to it. For every Green-dotted food a Googler buys, it’s free. For every Yellow-dotted food they buy, their account gets charged 50 cents and Google matches that 50 cents and donates it to charity--such as the theoretical “Hungry Kids Without Wi-Fi Foundation.” For every red-dotted food they buy, this goes up to a matched $1. Googlers could still have anything they wanted, but they’d have to pause for a second to think about how badly they wanted it.

To tackle the “I gained weight before I knew it” problem, Bob Evans, one of their software engineers, had an idea. Have you ever seen those iPhone or Android apps that let you upload a photo of yourself, and it shows you what you would look like if you were twenty or forty pounds skinnier or fatter? This would either motivate or scare the bejesus out of you. John figured there might be a way to have a “food scanner” set up that could scan someone’s tray and a camera and screen in front of them would take their photo and instantly display what they would look like in a year if they ate this much food every day for lunch. Way cool.

These adventures with the Google cafeterias are continuing, but they show how a few seemingly small changes can change a culture, and a waistline. Now let’s return to the real world of cafeteria cuisine and how it can better fit within your wellness program.

Second, they have amazingly super cool cafeterias that serve almost anything you would imagine (sushi, BBQ, curry, burgers, chili, Jell-O, dessert bars) and some foods you wouldn’t imagine (kale and pumpkin pizza). Grab a tray and pile it high. Go back for seconds if you wish. Repeat until you feel like your stomach is about to explode. And again, it’s all free, all the time. Management isn’t shy about saying why:[10]

• It’s a recruiting and retention plus.

• It keeps high-salaried software engineers on site rather than driving around for an hour looking for restaurant.

• It encourages good “accidental conversations” with other Googlers.

• It reduces bad “accidental conversations”--those involving trade secrets--with pesky neighborhood competitors.

Unfortunately, there’s also something called the “Google fifteen.” It’s the fifteen pounds new Googlers--they’re called Nooglers--are rumored to gain shortly after joining the clan. This isn’t unique to Google. There’s also the M&M/Mars fifteen and the Nabisco fifteen that happen at other headquarters. In fact, this probably happens at any company where there’s lots of tasty, widely available free food.

Some of the first steps to make the Micro Kitchens more slim by design were pretty straightforward. Armed with our cafeteria research findings (described in the next chapter), a student whose dissertation committee I was on, Jessica Wisdom, took a job with Google in People Analytics and started nudging things around.[11] We knew that the three things that determine what a person eats in a free food environment: 1) what’s most convenient, 2) what’s most attractive, and 3) what’s most normal.[12] So here’s what was done:

• All the healthy snacks--like fruits, baked things, and granola-ly things--were put on the top shelves and the less healthy snacks--like Kit-Kats and Peanut M&Ms--were reduced to the smaller “Fun Size” and put on the “I-can barely-see-it-from-here” bottom row.

• All the bottled waters and calorie-free flavored waters were put at eye level in the coolers and soft drinks at the bottom--water intake increased by 47 percent and drink calories dropped by 7 percent.

• Fruit bowls are now about the first and last thing you see.

• Candy is in opaque bins and not out in plain sight--9 percent less candy was taken in just the first week. [13]

The challenge with the Google Fifteen was to also figure out what to do about the massively tempting cafeterias. Our interviews with Googlers showed four complaints. Too much tasty variety led them to overeat, they wasted all sorts of food, they thought this was irresponsible and unsustainable, and they gained weight before they knew it – they had gained a Google Gut faster than they could say “The square root of 170 is 13.038.” Some small changes we recommended include:

• Putting the salad at the front of the line and the dessert at the back.

• Offering small plates to diners so they would take less--32 percent chose the smaller ones.[14]

• Downscaling the size of desserts to just three bites. They could still take a second or third helping, but not many do.[15]

One approach would be to reduce the variety of food. Sure, if Google only offered beans and rice, people won’t overeat . . . there. They’ll go off-campus to overeat--bad news. A better solution would be to make it less easy--but not impossible--to pile a four-foot stack of food on a tray. This could first be done by breaking that massive cafeteria into four smaller cafes based on the style of food--Asian, Vegetarian, Italian, and an American Grill. You could still pile on a four-foot stack of food; but you’d have to go in and out of four different doors--probably too much of a hassle for most people most of the time. Analogous to the 100-calorie pack, each time they left one of the four cafes, they’d have to ask themselves if they really wanted to visit the next one. They couldn’t blame Google for restricting their choices, they’d just think, Uhh . . . this is enough.

As for the complaints about irresponsibility and unsustainability, Google had a stoplight rating system for certain foods. Green was healthy, red was less healthy, and yellow was in-between. [16] Most people seemed to ignore it, so here’s what we suggested. Since every Googler has an ID card, they could have a debit account linked to it. For every Green-dotted food a Googler buys, it’s free. For every Yellow-dotted food they buy, their account gets charged 50 cents and Google matches that 50 cents and donates it to charity--such as the theoretical “Hungry Kids Without Wi-Fi Foundation.” For every red-dotted food they buy, this goes up to a matched $1. Googlers could still have anything they wanted, but they’d have to pause for a second to think about how badly they wanted it.

To tackle the “I gained weight before I knew it” problem, Bob Evans, one of their software engineers, had an idea. Have you ever seen those iPhone or Android apps that let you upload a photo of yourself, and it shows you what you would look like if you were twenty or forty pounds skinnier or fatter? This would either motivate or scare the bejesus out of you. John figured there might be a way to have a “food scanner” set up that could scan someone’s tray and a camera and screen in front of them would take their photo and instantly display what they would look like in a year if they ate this much food every day for lunch. Way cool.

These adventures with the Google cafeterias are continuing, but they show how a few seemingly small changes can change a culture, and a waistline. Now let’s return to the real world of cafeteria cuisine and how it can better fit within your wellness program.

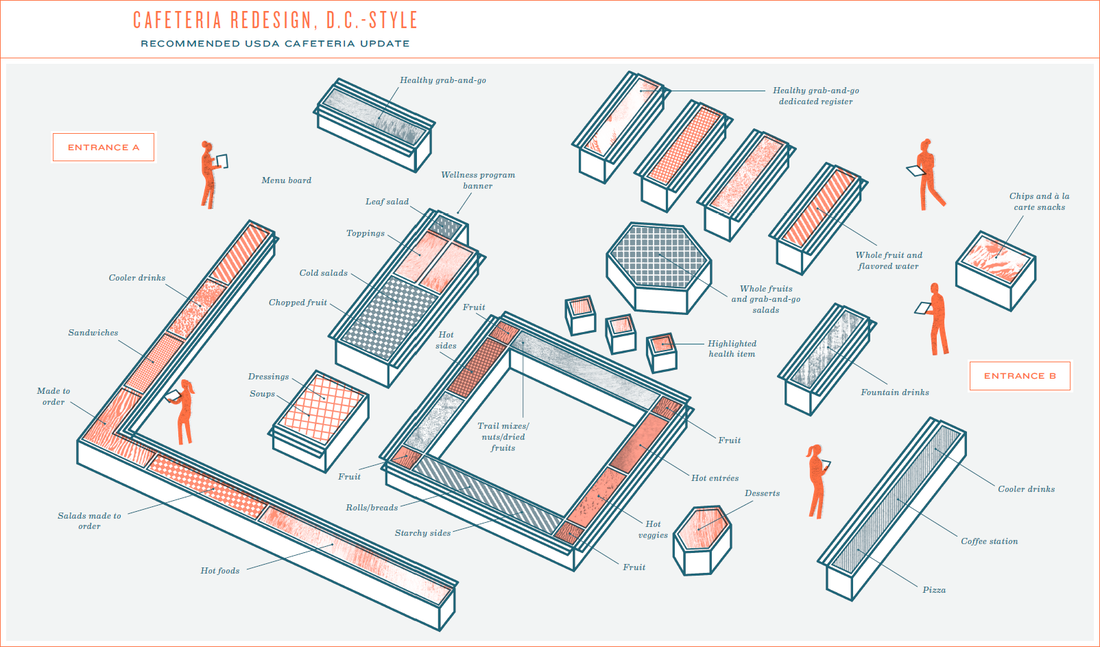

Making the USDA Cafeteria Healthier

(and a How To Guide for Your Company)

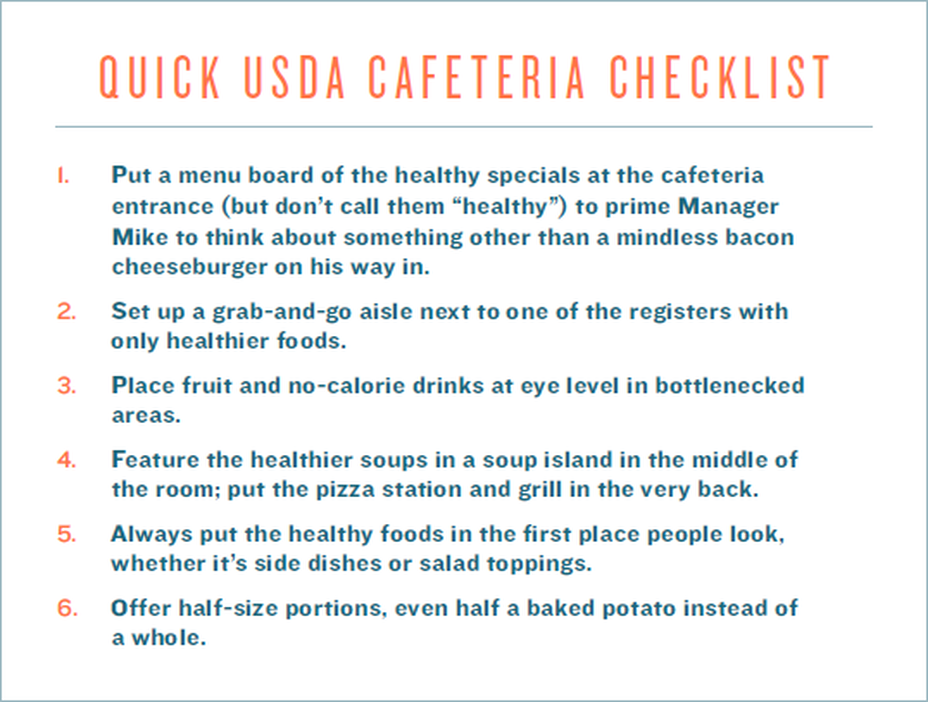

Few places other than Google offer tastier food at better prices than the United States Department of Agriculture’s cafeteria in Washington, DC. The USDA helps set the Dietary Guidelines, and they have nutrition nailed down: The cafeteria offers great whole-grain bread, huge salad bars, sushi, kimchee, low-fat desserts, and organic, gluten-free, vegetarian specials and they serve 1400 hungry lunch-goers every day. Yet what would make these lunch specials even more special would be if people actually bought them. Like all cafeterias, the USDA's privately-run cafeteria needs to make money, so in addition to the specials, they have incredible bacon cheeseburgers and gourmet pizza to round out your order of curly fries, and they have triple-chunky, full-fat blue cheese dressing and bacon strips to help your side salad provide 100 percent of your daily calorie needs.

But it doesn't matter how healthy the food is, as you well know by now, it’s not nutrition until it’s eaten. They asked us to help them figure how they could help guide people to the good stuff.

Here’s what happens most weekdays at 12:03: Manager Mike, stressed out and distracted by an urgent deadline, is hurrying down to grab a quick lunch. He’s going to charge right past the organic, gluten-free, vegetarian special and pick up his favorite default lunch: two slices of the Meat Blaster pizza. As he hurtles past the salad bar, he suddenly sees that the pizza line is too long and course-corrects to the bacon cheeseburger line. He grabs what looks like the biggest burger and curly fries and makes a beeline to the soft drinks and then to the cashier who’s closest to the cooler. By the time he arrives with his Coke, there are three people ahead of him. He impatiently shifts from leg to leg, looks around, and grabs a chocolate chunk cookie from the display next to him.

Given Mike’s mindset, it’s going to be hard to convince him to ditch his bacon cheeseburger for a whole-grain turkey sandwich and a banana. That’s what most “healthy” cafeterias do wrong. They think they can move Mike to the turkey sandwich by giving him calorie information that compares bananas and bacon. The smarter approach would be to get him to take the turkey sandwich without thinking about it. A senior USDA adviser asked us to help.

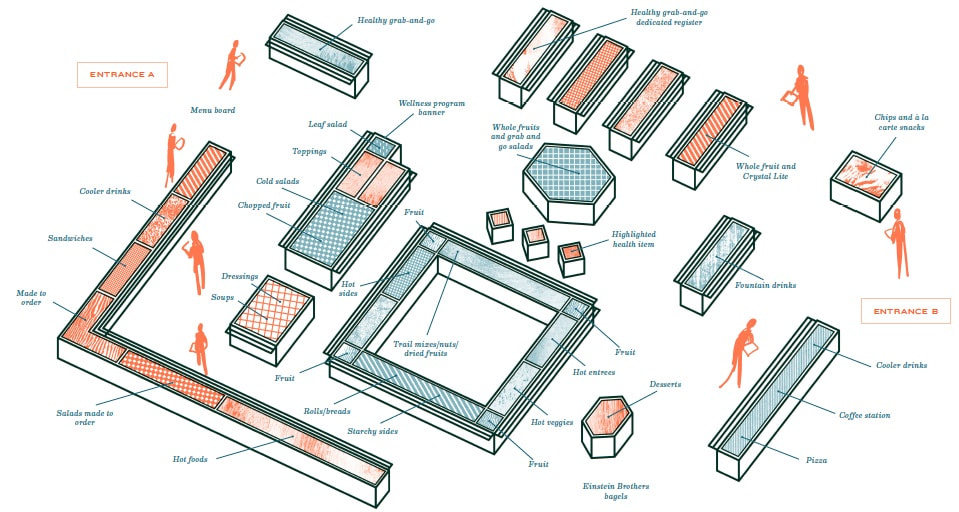

Four of us from the Lab photographed food layouts and signage, mapped out traffic flow paths, and recorded the relevant decision times and wait times for the lunch crowd. When we send teams to do corporate cafeteria makeovers, we’ll usually recommend the top six changes we think will be the easiest, quickest, and most effective to make. After they make these, we’ll suggest others. Here are the first six we gave the USDA.[18]

But it doesn't matter how healthy the food is, as you well know by now, it’s not nutrition until it’s eaten. They asked us to help them figure how they could help guide people to the good stuff.

Here’s what happens most weekdays at 12:03: Manager Mike, stressed out and distracted by an urgent deadline, is hurrying down to grab a quick lunch. He’s going to charge right past the organic, gluten-free, vegetarian special and pick up his favorite default lunch: two slices of the Meat Blaster pizza. As he hurtles past the salad bar, he suddenly sees that the pizza line is too long and course-corrects to the bacon cheeseburger line. He grabs what looks like the biggest burger and curly fries and makes a beeline to the soft drinks and then to the cashier who’s closest to the cooler. By the time he arrives with his Coke, there are three people ahead of him. He impatiently shifts from leg to leg, looks around, and grabs a chocolate chunk cookie from the display next to him.

Given Mike’s mindset, it’s going to be hard to convince him to ditch his bacon cheeseburger for a whole-grain turkey sandwich and a banana. That’s what most “healthy” cafeterias do wrong. They think they can move Mike to the turkey sandwich by giving him calorie information that compares bananas and bacon. The smarter approach would be to get him to take the turkey sandwich without thinking about it. A senior USDA adviser asked us to help.

Four of us from the Lab photographed food layouts and signage, mapped out traffic flow paths, and recorded the relevant decision times and wait times for the lunch crowd. When we send teams to do corporate cafeteria makeovers, we’ll usually recommend the top six changes we think will be the easiest, quickest, and most effective to make. After they make these, we’ll suggest others. Here are the first six we gave the USDA.[18]

The day after changes such as these are made, it’s amusing to watch what people do. People like Manager Mike plow into the cafeteria, jolt to a stop, hold their breath for a second, and look like they’ve accidentally wandered into an alternate Twilight Zone reality. They then start to tentatively creep around like it’s their first day at work. For the first couple weeks they usually buy the exact foods they used to buy. It’s almost as if being in a strange environment makes them want their favorite foods so they can feel more in control. But after a couple weeks, people become more familiar with the layout and start acting mindlessly again. This time, however, the healthy foods have an edge: Mike’s been pre-alerted to them by the “Today’s Specials” sign at the entrance, they’re the first foods he sees, and they’re always the most convenient. Before the cafeteria knows it, they’re out of turkey sandwiches because Mike just took the last one.

What About Your Company Health Club -- Does it Help?

Fitness trainers have a saying: “Health clubs are where New Year’s resolutions go to die.” Companies have high hopes for any new fitness center, workout room, or walking trail they build. But like our New Year’s resolutions, they’re high hopes with low results.

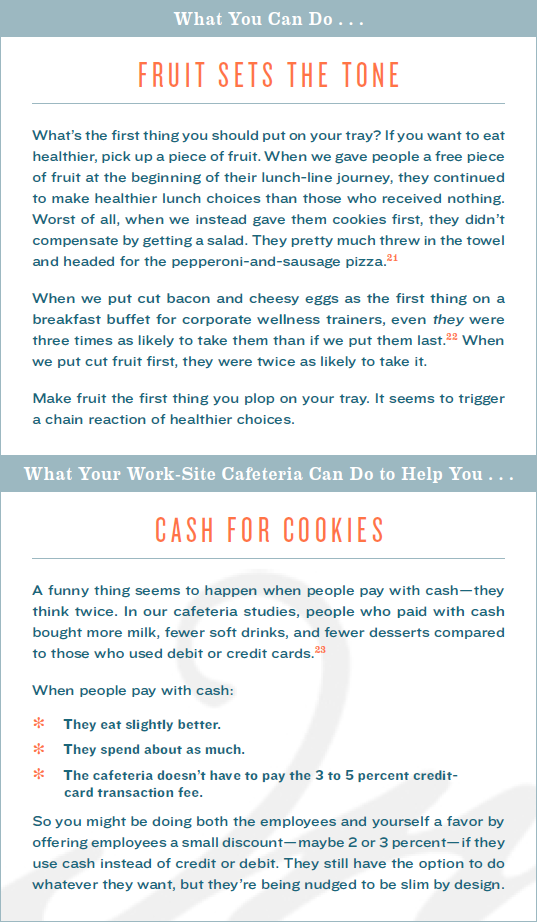

There are two real problems with health clubs. First, most of us don’t like to exercise. Sure, we can get hooked on what it gives us--an energy boost, an endorphin high, or six-pack abs--but we don’t inherently like to exercise. It’s a means to an end. Even the inspiringly wacky Jack LaLanne--the guy who once swam up the Mississippi River with twelve rowboats chained behind him--said, “I hate to exercise. It’s very hard to leave a warm bed and a hot woman for a cold gym.” He said that when he was ninety-four (and when his wife was eighty-three).[22]

The second problem is that we use exercise as an excuse to eat more. Ever start a new exercise program and gain weight instead losing it? Join the club. It’s often the case that a new gym membership comes with three pounds of fat attached to it. We work out and then crack open a pint of Haagen-Dazs or eat a bigger dinner because we feel that we earned it. Remember, one hour on the treadmill is erased in the two minutes it takes to get back to inhale the vintage food stash at your desk.

There are two real problems with health clubs. First, most of us don’t like to exercise. Sure, we can get hooked on what it gives us--an energy boost, an endorphin high, or six-pack abs--but we don’t inherently like to exercise. It’s a means to an end. Even the inspiringly wacky Jack LaLanne--the guy who once swam up the Mississippi River with twelve rowboats chained behind him--said, “I hate to exercise. It’s very hard to leave a warm bed and a hot woman for a cold gym.” He said that when he was ninety-four (and when his wife was eighty-three).[22]

The second problem is that we use exercise as an excuse to eat more. Ever start a new exercise program and gain weight instead losing it? Join the club. It’s often the case that a new gym membership comes with three pounds of fat attached to it. We work out and then crack open a pint of Haagen-Dazs or eat a bigger dinner because we feel that we earned it. Remember, one hour on the treadmill is erased in the two minutes it takes to get back to inhale the vintage food stash at your desk.

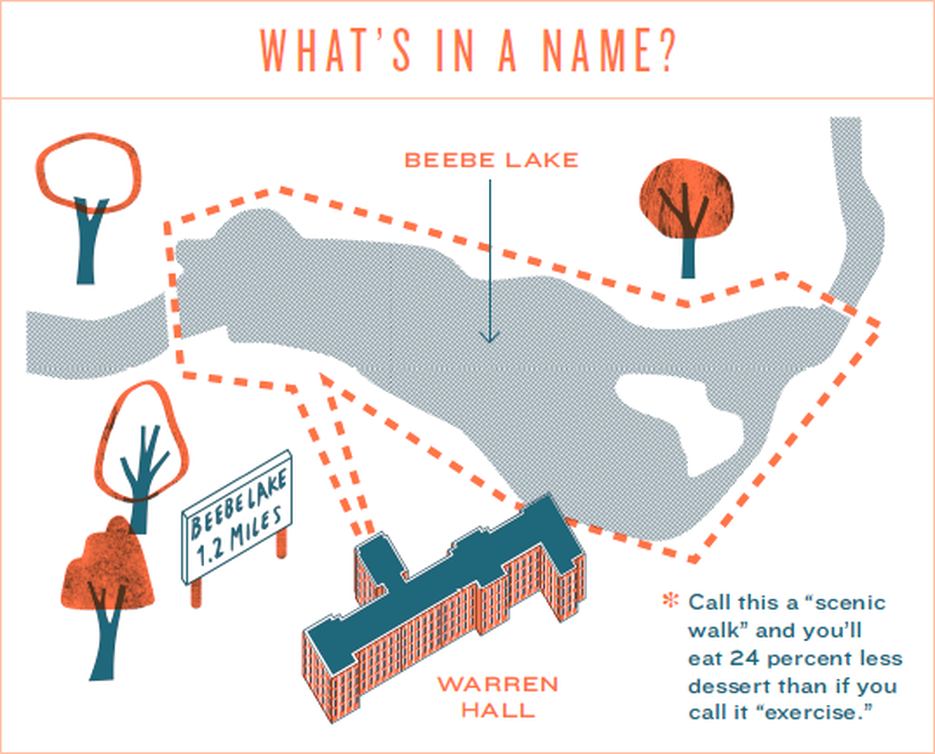

If we don’t really like exercising and unknowingly use it as an excuse to eat more, we have three options: 1) we can exercise more and eat less, 2) we can avoid it, or 3) we can do it, but not call it "exercise." Just as we can trick ourselves into mindlessly eating better, we can trick ourselves into mindlessly exercising.

Suppose your company built a walking trail around its building (or in it). Walking trails are nice, but don’t pin high hopes on their wellness results. Lunchtime is short, and walking trails aren’t that alluring--particularly during the winter. In one snow-belt company we even built a walking trail through the factory--using a nice bright yellow line and distance markers – but this didn’t move the obesity dial. It got a few more office workers walking, but nothing more. When it comes to working out at work, most of us have 1) no time, or 2) no interest.

Exercise is tough to inspire. Sure, there are a few employees who’ll do Pilates and use the Buns-of-Steel-Meister machine in the gym, but they probably would have done it in a different gym anyway. Sure, there will be the Marine Corps Marathon runners and the shirtless Matterhorn climber, but it probably wasn’t the company’s “Exercise Now for Fun and Good Health” flier that did it. These people were already working out.

But a company can make some changes that make it necessary for everyone to move a little more. Changes that make them walk a little farther to the restrooms, or farther from the parking lot. One company moved its walkways from the parking lots so they wrapped around the scenic back of the building instead into the cold front foyer. Even though some people initially complained when it rained, walking three times as far for a more beautiful view seemed worth it for most. When Steve Jobs was at Pixar, he proposed idea of having only one central bathroom: great for exercise and collaboration, less great for emergencies.[25]

Exercise is tough to inspire. Sure, there are a few employees who’ll do Pilates and use the Buns-of-Steel-Meister machine in the gym, but they probably would have done it in a different gym anyway. Sure, there will be the Marine Corps Marathon runners and the shirtless Matterhorn climber, but it probably wasn’t the company’s “Exercise Now for Fun and Good Health” flier that did it. These people were already working out.

But a company can make some changes that make it necessary for everyone to move a little more. Changes that make them walk a little farther to the restrooms, or farther from the parking lot. One company moved its walkways from the parking lots so they wrapped around the scenic back of the building instead into the cold front foyer. Even though some people initially complained when it rained, walking three times as far for a more beautiful view seemed worth it for most. When Steve Jobs was at Pixar, he proposed idea of having only one central bathroom: great for exercise and collaboration, less great for emergencies.[25]

What's the Best Coaching and Weight-loss Program for My Company?

Weight loss is often a key corporate wellness goal. But there’s no one-size-fits-all solution. People try to do it in all sorts of different ways. As mentioned in chapter 1, some people count calories, some use support groups, some use a fad diet, some skip dessert. People often ask, “What’s your best tip?” But the changes or “tips” my family has made to be slim by design might be impractical or ineffective for the family next door or the single guy across the street.

I was recently asked by a large employee union to contribute to a program that would help their employees lose weight. Instead of a one-size-fits-all plan, it became a choose-whatever-you-want plan--a wellness buffet. They reimbursed each employee’s insurance premium for the year as long as they participated in a few activities for just the first six months of the year. After that they could choose to do what they wanted.

They were then given a list of forty to fifty activities, like go to a gym three times per week, join a worksite TOPS (Take Off Pounds Sensibly) program, take a ballroom dancing class, join a paintball league, sign up for nutrition seminars, take a meditation class, join an online weight loss program, and so on.[27] Different activities were worth different points, and as long as your activities added up to 100 points or more, the company paid your premium.

Why should your company care whether you bowl, meditate, or Rumba? Two reasons: It makes you more productive, and it saves them money. They save money if you don’t need to take as many sick days as you took last year and if you don’t have to go to the doctor as often. And they save a whole lot of money if you don’t need dozens of prescriptions, undergo heart bypass surgery, or have your stomach stapled.

The program was successful because people could get healthier doing what they wanted to do. Some picked activities that would make them slim by design, and others picked activities that gave them more balance in their lives. But it doesn’t really matter--we usually find that both plans intersect. People who lost weight seemed to get more balance in their lives and vice-versa--people who seemed to get more balance in their lives lost weight.

Yet even with these plans, it takes a motivated person to join up and do something they don’t have to really do. It relies on you wanting to take extra effort and time. Sometimes that’s asking a lot, especially since it wasn’t what you agreed to when you signed on for the job. But what if it had been . . .

I was recently asked by a large employee union to contribute to a program that would help their employees lose weight. Instead of a one-size-fits-all plan, it became a choose-whatever-you-want plan--a wellness buffet. They reimbursed each employee’s insurance premium for the year as long as they participated in a few activities for just the first six months of the year. After that they could choose to do what they wanted.

They were then given a list of forty to fifty activities, like go to a gym three times per week, join a worksite TOPS (Take Off Pounds Sensibly) program, take a ballroom dancing class, join a paintball league, sign up for nutrition seminars, take a meditation class, join an online weight loss program, and so on.[27] Different activities were worth different points, and as long as your activities added up to 100 points or more, the company paid your premium.

Why should your company care whether you bowl, meditate, or Rumba? Two reasons: It makes you more productive, and it saves them money. They save money if you don’t need to take as many sick days as you took last year and if you don’t have to go to the doctor as often. And they save a whole lot of money if you don’t need dozens of prescriptions, undergo heart bypass surgery, or have your stomach stapled.

The program was successful because people could get healthier doing what they wanted to do. Some picked activities that would make them slim by design, and others picked activities that gave them more balance in their lives. But it doesn’t really matter--we usually find that both plans intersect. People who lost weight seemed to get more balance in their lives and vice-versa--people who seemed to get more balance in their lives lost weight.

Yet even with these plans, it takes a motivated person to join up and do something they don’t have to really do. It relies on you wanting to take extra effort and time. Sometimes that’s asking a lot, especially since it wasn’t what you agreed to when you signed on for the job. But what if it had been . . .

Do Health Conduct Codes Work and Would You Sign One?

Imagine if part of your job description was to be healthy. Most companies have a company manual and a conduct code you sign when you start. It tells you generally how to handle company property (“no stealing”), how to deal with co-workers (“no touching”), how to dress (“no mesh T-shirts or Speedos”). We read it, and if want the job badly enough, we drink the company Kool-Aid, sign it, and we save our black mesh T-shirt for the weekend.

What if a new Silicon Valley company—LeederLab--also had a behavior code related to health? They didn’t grade you on your cholesterol or your blood pressure, but you had to agree to exercise at least two days a week, and you had to have an annual physical. Also, if your BMI exceeded 30 at your annual physical, you had to agree to join a weight-loss group--like a company-sponsored TOPS or Weight Watchers program. In all of these cases, the company would pay for the program and give you company time to attend it. Maybe new employees could choose to opt out and not sign the code, but they’d then have to pay for part of their health benefits--or have a higher co-pay.

If you had already worked for the company, you’d be grandfathered in, but here’s what would probably happen. Once exercise and BMI weight loss programs began to be the norm, the grandfathered employees might also start to "up" their game. If they liked their job, they’d probably--almost subconsciously--gradually step in line. If they weren’t that crazy with their job, they’d probably--again almost subconsciously--gradually start looking for a new place to work. Once health started to become the behavioral norm at the company, eating another full box of Samoa Girl Scout cookies at your desk for lunch would become the equivalent of bringing a bong into a board meeting.

This would be a bold and committed company. Some people might decide not to join the company, but those who did would agree to this health code of conduct. This company—LeederLab--doesn’t exist yet. But it wouldn’t have to be a Silly Valley company that only hires twenty-year-old Stanford computer science grads. With a different name, there’s no reason it couldn’t be a power company in Bozeman or a newspaper company in Baton Rouge.

What if a new Silicon Valley company—LeederLab--also had a behavior code related to health? They didn’t grade you on your cholesterol or your blood pressure, but you had to agree to exercise at least two days a week, and you had to have an annual physical. Also, if your BMI exceeded 30 at your annual physical, you had to agree to join a weight-loss group--like a company-sponsored TOPS or Weight Watchers program. In all of these cases, the company would pay for the program and give you company time to attend it. Maybe new employees could choose to opt out and not sign the code, but they’d then have to pay for part of their health benefits--or have a higher co-pay.

If you had already worked for the company, you’d be grandfathered in, but here’s what would probably happen. Once exercise and BMI weight loss programs began to be the norm, the grandfathered employees might also start to "up" their game. If they liked their job, they’d probably--almost subconsciously--gradually step in line. If they weren’t that crazy with their job, they’d probably--again almost subconsciously--gradually start looking for a new place to work. Once health started to become the behavioral norm at the company, eating another full box of Samoa Girl Scout cookies at your desk for lunch would become the equivalent of bringing a bong into a board meeting.

This would be a bold and committed company. Some people might decide not to join the company, but those who did would agree to this health code of conduct. This company—LeederLab--doesn’t exist yet. But it wouldn’t have to be a Silly Valley company that only hires twenty-year-old Stanford computer science grads. With a different name, there’s no reason it couldn’t be a power company in Bozeman or a newspaper company in Baton Rouge.

But would you want to work for a company that had a health conduct code?

It’s surprising how many people would. My colleague Rebecca Robbins and I found that most employees say they’d sign these codes if the requirements were simple--like getting an annual physical or screening exams--and if it came with discounts on insurance, medications, examinations, or even a donation to a favorite charity. Most people liked the idea of the health contract. It didn’t matter if they were male or female, young or old. What did matter was their weight. People who were just a little overweight loved it and thought it would motivate them. But people who were a lotoverweight (BMI over 30) were not as giddy.[31]

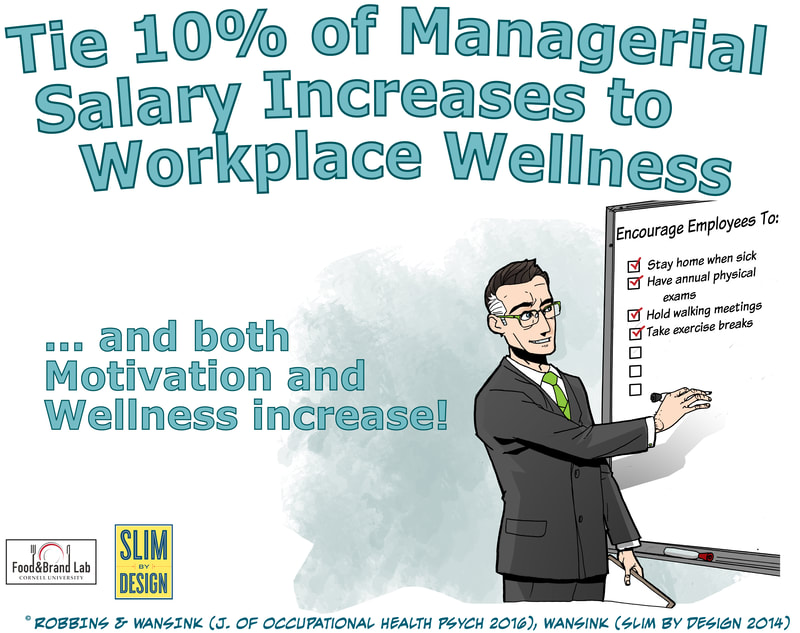

Your company probably won’t introduce a Health Conduct Code on Monday, but it might be coming soon. Meanwhile, there are two changes your CEO could make that would quickly help make your whole company more slim by design. The first would be to institute a Health Conduct Code. The second would be to change the job description of your boss.

Design Your New Boss’s Job Description!

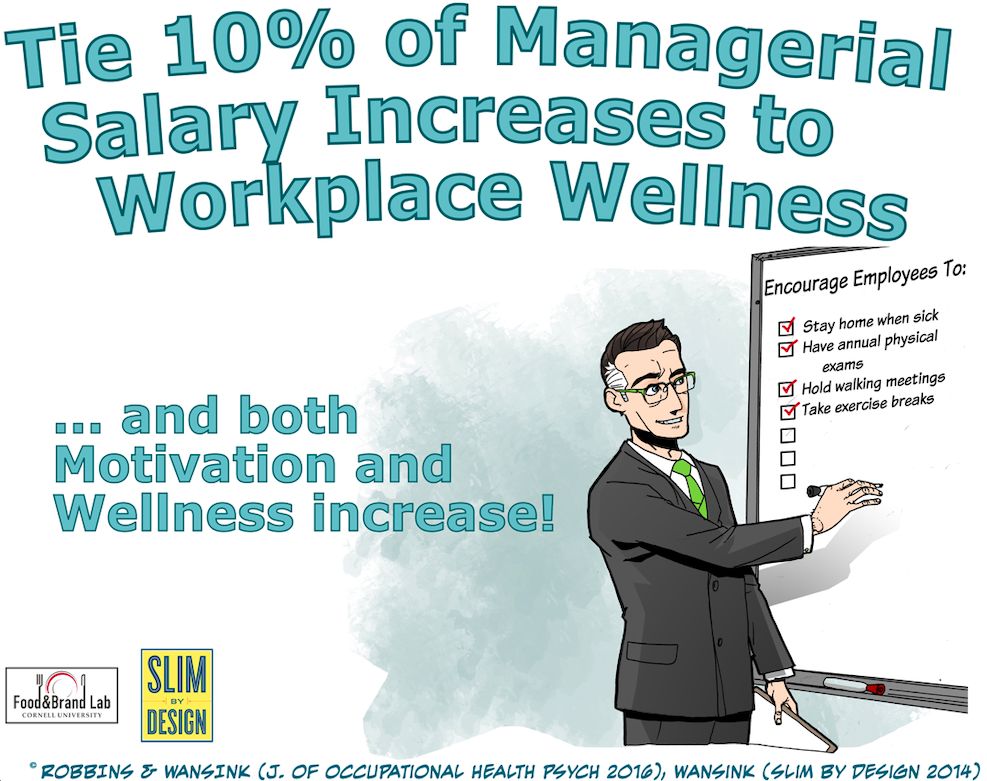

Suppose your boss’s job description stated that 10 percent of her pay raise or promotion depended on what she had done this past year to try to improve your health. Things would quickly change--break rooms, cafeterias, and facility rooms would be improved to nudge you to eat a little better and move a little more. Big transformations don’t happen until people are rewarded for wellness.

Who’s more productive: The woman who combines 36 hours of desk work with four hours of company time at yoga, or the guy who slugs it out for 50 hours every week? Hmmm . . . John Peters, the chief strategy officer of the University of Colorado Anschutz Wellness Center asked once asked me that. At some point, those 14 extra hours might be resented and not add up--they might actually begin to subtract. Thirty-six hours of energized work might be worth a lot more than 50 hours of stressed-out, perhaps embittered, exhaustion.

Imagine what would happen if your boss--along with other managers in your company--were graded and promoted partly on how she tried to help make you healthier. Again, healthy employees are good for business--fewer sick days, fewer medications, and fewer heart attacks. Yet if only 10 percent of your manager’s annual evaluation was based on what she did last year to help improve the health of his direct report employees, like you, it would be okay--not weird--for you to sit on a highway cone-orange exercise ball chair instead of a black office chair. One-on-one walking meetings would become normal, and desktop lunches might start to look anti-social. You might be thanked when you bring in fruit for your birthday but given the stink eye if you brought two dozen donuts or 5 pounds of bagels.

Who’s more productive: The woman who combines 36 hours of desk work with four hours of company time at yoga, or the guy who slugs it out for 50 hours every week? Hmmm . . . John Peters, the chief strategy officer of the University of Colorado Anschutz Wellness Center asked once asked me that. At some point, those 14 extra hours might be resented and not add up--they might actually begin to subtract. Thirty-six hours of energized work might be worth a lot more than 50 hours of stressed-out, perhaps embittered, exhaustion.

Imagine what would happen if your boss--along with other managers in your company--were graded and promoted partly on how she tried to help make you healthier. Again, healthy employees are good for business--fewer sick days, fewer medications, and fewer heart attacks. Yet if only 10 percent of your manager’s annual evaluation was based on what she did last year to help improve the health of his direct report employees, like you, it would be okay--not weird--for you to sit on a highway cone-orange exercise ball chair instead of a black office chair. One-on-one walking meetings would become normal, and desktop lunches might start to look anti-social. You might be thanked when you bring in fruit for your birthday but given the stink eye if you brought two dozen donuts or 5 pounds of bagels.

This is radical thinking. That’s why it’s surprising that so many managers are in favor of it. Again, we found that most managers thought that having this health clause in their contracts would clearly incentivize them to make their employees more happy, productive, and cooperative. [34] They also liked how most of the changes would be quick and easy to implement -- they didn't have to do anything drastic like install a company Jai-Alai court or polo field. We also asked them if they would rather work for Acme Corporation, which did not have 10 percent of their evaluation tied to wellness, or Shangri-La Corporation, which did. Sixty-four percent wanted to work for Shangri-La. They said they believed it would be a more dynamic, progressive industry leader, with room for more advancement.

Every company talks about health and wellness, but really they’re either committed to it or they aren’t. If they’re committed, they need to visualize what this new company looks like--it’s can't just have a walking trail, a diabetes brochure, or fruit cups in the cafeteria. There’s an expression in business that you motivate what you measure. If your boss measures how many insurance policies you sell, how many widgets you make, or how long you spend at their desk, that’s what you focus on. If they don’t measure it, you don’t take it quite as seriously.

Every company talks about health and wellness, but really they’re either committed to it or they aren’t. If they’re committed, they need to visualize what this new company looks like--it’s can't just have a walking trail, a diabetes brochure, or fruit cups in the cafeteria. There’s an expression in business that you motivate what you measure. If your boss measures how many insurance policies you sell, how many widgets you make, or how long you spend at their desk, that’s what you focus on. If they don’t measure it, you don’t take it quite as seriously.

What if we measured how hard our company worked to make us healthier? Unless you were sleep-reading through the last three chapters, it’s not surprising that a Scorecard can be an effective way to see how they measure up. This Slim by Design Scorecard is one of the quick assessments we use when working with companies to help make their employees healthier. Just like the scorecards for supermarkets and restaurants, it will show your boss or your wellness director how their company stacks up, and what they can specifically do to show leadership in wellness. It will give them some specific changes they can make right away, and it also lets them know someone really cares and might be measuring them. That’s motivating.

Company Wellness Programs Should be More Like Summer Camp, and Not Like Boot Camp

Remember the four pillars of most company wellness efforts and their tenth-grade counterparts? A health education program (health class), company fitness center (gym), new cafeteria foods (boring school lunches), and incentives (grades). It’s not surprising that most of these back-to-school-style company efforts don’t have widespread or enduring results. Just as when we were fifteen, we resented “the man” telling us what to do--regardless of how good it is for us.

If company wellness programs are ignored by most workers and used fitfully by others, maybe a better approach would be to change the workplace so that everyone moves in the right direction without resisting. Instead of thinking of wellness programs as boot camp--where everyone’s going to get whipped into shape--a better metaphor might be summer camp. Whether it’s basketball camp, band camp, church camp, or econometrics camp, summer camps are usually designed so kids can arrange their days to do a lot of what they want.

Companies need to be more like camps. If employees usually grumpily eat lunch hunched over a screen at their desk, the company should give them a reason to move--like a magnetically attractive break room, brownbag seminar series, or maybe even a fitness room with occasional programs. If employees reach for the cafeteria cheeseburger and fries by default, the company needs to tilt the cafeteria in the direction of the healthier foods so they’re the first foods people think about, see, and conveniently grab. If the company is going to give a discount to join health-related activities, they need to give lots of options. That is what a truly great company wellness program would do. It would help us become slim by design--not slim in spite of it.

If company wellness programs are ignored by most workers and used fitfully by others, maybe a better approach would be to change the workplace so that everyone moves in the right direction without resisting. Instead of thinking of wellness programs as boot camp--where everyone’s going to get whipped into shape--a better metaphor might be summer camp. Whether it’s basketball camp, band camp, church camp, or econometrics camp, summer camps are usually designed so kids can arrange their days to do a lot of what they want.

Companies need to be more like camps. If employees usually grumpily eat lunch hunched over a screen at their desk, the company should give them a reason to move--like a magnetically attractive break room, brownbag seminar series, or maybe even a fitness room with occasional programs. If employees reach for the cafeteria cheeseburger and fries by default, the company needs to tilt the cafeteria in the direction of the healthier foods so they’re the first foods people think about, see, and conveniently grab. If the company is going to give a discount to join health-related activities, they need to give lots of options. That is what a truly great company wellness program would do. It would help us become slim by design--not slim in spite of it.

Evidence-based Support and Published References

[1] Yeah, I know, who would ever do a study on something as silly as this? Brian Wansink, Aner Tal, Katheryn I. Hoy, and Adam Brumburg (2012), “Desktop Dining: Eating More and Enjoying it Less?” Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 44:4 (July-August), S62.

[2] Just like when we order the hot fudge sundae without the cherry – because we’re on a diet.

[3] A great observation by my friend John C. Peters, a long-time executive for Procter & Gamble and now the chief strategy officer of the University of Colorado Anschutz Wellness Center.

[4] Generally, the ROI for spending on worker health promotion is believed to be about three to one, not including improved employee morale and retention: Ron Z. Goetzel and Ronald J. Ozminkowski, “That’s Holding Your Back: Why Should (or Shouldn’t) Employers Invest in Health Promotion Programs for Their Workers?” North Carolina Medical Journal (November/December 2006), p. 429; Josh Cable, “The ROI of Wellness,” EHS Today: The Magazine for Environment, Health and Safety Leaders (April 13, 2007); Katherine Baicker, David Cutler and Zirui Song, “Workplace Wellness Programs Can Generate Savings,” Health Affairs (February 2010), pp. 1-7.

[5] These plans work a little bit for a few people. That is, they might lead some fit-minded folks to shift from their personal gym to the company gym, the cafeteria might sell a few more salads each day, or they might lead one fitness challenge team to lose 8 pounds each until it creeps back on over the winter. Some examples of financial incentives include a $250 cash bonus for a 10 percent weight loss, $150 for participating in programs, subsidies for gym and Weight Watchers memberships, and discount coupons for healthy foods.

[6] Some modestly successful wellness programs in four very different industries include Johnson & Johnson (annual savings of $224.66 per employee), IBM (saved $2.42 for every $1 spent on wellness), H-E-B Grocery (health care costs increased only one-third of national average), and Lincoln Industries (cut workers compensation claims in down from $510,000 to $43,000 in one year).

[7] This 60-30-10 breakdown Human Resources people throw around as a rough approximation.

[8] This also works great for children: Andrew S. Hanks, David R. Just, and Brian Wansink (2013), “Pre-Ordering School Lunch and Food Choices Encourages Better Food Choices by Children,” JAMA Pediatrics, 167:7, 673-674.

[9] On place to find free posters is from here: wellnessproposals.com/wellness-library/nutrition/nutrition-posters/ and

[10] From Ricky W. Griffin and Gregory Moorhead, Organisational Behaviour: Managing People and Organisations, South Western, 9th Edition, pp. 522-524.

[11] An account of our work can be found here: Cliff Kuang (2012) “In the Cafeteria, Google Gets Healthy,” Fast Company, April 2012.

[12] More at David R. Just and Brian Wansink (2009), “Better School Meals on a Budget: Using Behavioral Economics and Food Psychology to Improve Meal Selection,” Choices, 24:3, 1-6, and at Brian Wansink (2013), “Convenient, Attractive, and Normative: The CANApproach to Making Children Slim by Design, Childhood Obesity, 9:4 (August), 277-278.

[13] The basic study was first shown in James E. Painter, Brian Wansink, and Julie B. Hieggelke (2002), “How Visibility and Convenience Influence Candy Consumption,” Appetite, 38:3 (June), 237-238. The 9% drop was reported by Jennifer Kurkoski and Jessica Wisdom to Cliff Kuang in Fast Company, April 2012.

[14] The general figure our research has discovered is closer to 22% for the average person, but this 32% increase was reported by Jennifer Kurkoski and Jessica Wisdom to Cliff Kuang in Fast Company, April 2012.

[15] This is a great way to eat smaller snacks – eat only ¼ as much and distract yourselve for 15 minutes returning phone calls or straightening up: Ellen Van Kleef, Mitsuru Shimizu, and Brian Wansink (2013), “Just a Bite: Considerably Smaller Snack Portions Satisfy Delayed Hunger and Craving,” Food Quality and Preference, 27:1, 96-100.

[16] A major drawback is that they are very subjective in where the line is drawn – is 1% milk a red light or a yellow light? When consumers think there is too much subjectivity, they either ignore it or react against it.

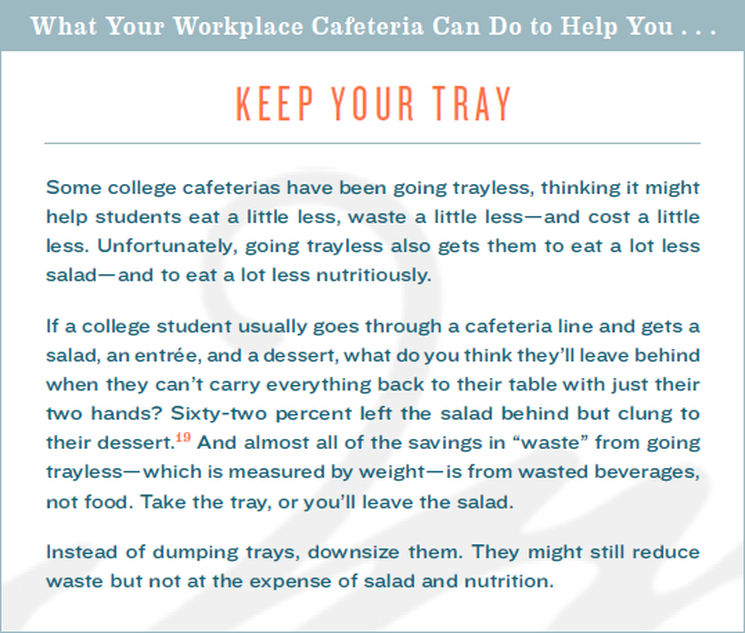

[17] This is a cool study on lunch trays with unexpected results: Brian Wansink and David R. Just (2014), “Trayless Cafeterias Lead Diners to Take Less Salad and Relatively More Dessert,” Public Health Nutrition, forthcoming.

.

[18] The full list of all of the changes is available at SlimByDesign.org.

[19] Always serve the healthy things first, even at home. Brian Wansink and Aner Tal (2014), “The Power of Healthy Primes When Selecting Meals,” under review.

[20] Here’s the best reason to start at the healthiest part of the buffet line: Brian Wansink and Andrew S. Hanks (2013), “Slim by Design: Serving Healthy Foods First in Buffet Lines Improves Overall Meal Selection,” PLoS One, 8:10, e77055.

[21] One great solution to this is to have cards limited so they can only buy healthy items. More at Brian Wansink, David R. Just and Collin R. Payne (2013), The Behavioral Economics of Healthier School Lunch Payment Systems, under review.

[22] I’ve heard this quote a number of times. Here’s a secondary citation of it: http://www.instantdane.tv/ultimate-fitness-guru-taught-how-to-stay-fit/. This guy is truly a studly “Just do it” inspiration. Check him out on YouTube.

[23] In the beginning, we held Consumer Camp for anyone who had participated in a study of ours over the prior year. When people are in a study, there’s always some of them who want to know the results. Consumer Camp is a much more fun way to tell them what we’ve been doing than sending out a form e-mail. Over the years we’ve had people from 37 different states attend Consumer Camp. We’ve never limited now many people could attend. More information and registration details can be found at foodpsychology.cornell.edu/content/consumer-camp.

[24] The same thing happens even if you ask people to just “think” about exercising. See Werle, Carolina O. C., Brian Wansink, and Collin R. Payne (2011), “’Just Thinking About Exercise Makes Me Serve More Food:’ Physical Activity and Calorie Compensation,” Appetite, 56:2 (April), 332-335.

[25] Described in Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011.

[26] This changed the whole way my Lab has viewed exercise . . . for the better: Carolina O.C. Werle, Brian Wansink, and Collin R. Payne,, “The Effect of Distraction in Sequential Actions: When Fun Exercising Avoids Indulgence,” forthcoming.

[27] The basic design of the weight-loss portion of this was presented at the Experimental Biology conference in 2011: Brian Wansink, Aner Tal, and Mitsuru Shimizu (2011), “The Wichita ‘One-Ton’ Weight Loss Program: Community Weight Loss and the National Mindless Eating Challenge, FASEB Journal, 25:974.2.

[28] Details about the program can be found in the article in the next footnote along with this more general version: Brian Wansink (2010), “From Mindless Eating to Mindlessly Eating Better,” Physiology & Behavior, 100:5, 454-463.

[29] When Mindless Eating was published, we were indulged with calls and emails – maybe 800 a week – asking what would be the one or two biggest changes that a person could make in their life that would make the biggest difference in helping them mindlessly eat less. To help each of these people and not lose our lives, we developed the National Mindless Eating Challenge. We directed these people to a website that asked them eighteen different questions, and based on these questions, we presented them with the three small changes they could make that would cause them to lose weight. Not a lot of weight—just 1 or 2 pounds a month—but they would be doing it without dieting, and the number on the scale would be moving in the right direction.

[30] We focused on those who adhered to at least one change they were given. See more at Kirsikka Kaipaninen, Collin R. Payne, and Brian Wansink (2012), “The Mindless Eating Challenge: Retention, Weight Outcomes, and Barriers for Changes in a Public Web-based Healthy Eating and Weight Loss Program,” Journal of Medical Internet Research, 14:6, e168.

[31] If you work in company wellness, you’ll find this article useful. It shows what you can put in these contracts and what to leave out, Rebecca S. Robbins and Brian Wansink (2014), “Designing Employee Health Contracts to be Slim by Design,” forthcoming.

[32] Although this is an early article on this law, there’s not a lot that’s been reported since then that is of much note: Norimitsu Onishi (2008), “Japan, Seeking Trim Waists, Measures Millions,” New York Times (June 13, 2008).

[33] The exact number reported by the AFP agency is 12.3, but I conservatively rounded up because this strikes me strangely too low for such a disciplined country with such strong social norms. Here’s the details: Jacques Lhuillery (2013) “Breaking the Law, one sushi roll at a time,” AFP, (AFP.com/en/node/804444), January 25, 2013.

[34] This is radical thinking, so it’s surprising so many managers seem to be behind it. Download this article at the Social Science Research Network, Rebecca S. Robbins and Brian Wansink (2014) “Evaluating Managers Based on the Wellness of Their Employees,” forthcoming.

[2] Just like when we order the hot fudge sundae without the cherry – because we’re on a diet.

[3] A great observation by my friend John C. Peters, a long-time executive for Procter & Gamble and now the chief strategy officer of the University of Colorado Anschutz Wellness Center.

[4] Generally, the ROI for spending on worker health promotion is believed to be about three to one, not including improved employee morale and retention: Ron Z. Goetzel and Ronald J. Ozminkowski, “That’s Holding Your Back: Why Should (or Shouldn’t) Employers Invest in Health Promotion Programs for Their Workers?” North Carolina Medical Journal (November/December 2006), p. 429; Josh Cable, “The ROI of Wellness,” EHS Today: The Magazine for Environment, Health and Safety Leaders (April 13, 2007); Katherine Baicker, David Cutler and Zirui Song, “Workplace Wellness Programs Can Generate Savings,” Health Affairs (February 2010), pp. 1-7.

[5] These plans work a little bit for a few people. That is, they might lead some fit-minded folks to shift from their personal gym to the company gym, the cafeteria might sell a few more salads each day, or they might lead one fitness challenge team to lose 8 pounds each until it creeps back on over the winter. Some examples of financial incentives include a $250 cash bonus for a 10 percent weight loss, $150 for participating in programs, subsidies for gym and Weight Watchers memberships, and discount coupons for healthy foods.

[6] Some modestly successful wellness programs in four very different industries include Johnson & Johnson (annual savings of $224.66 per employee), IBM (saved $2.42 for every $1 spent on wellness), H-E-B Grocery (health care costs increased only one-third of national average), and Lincoln Industries (cut workers compensation claims in down from $510,000 to $43,000 in one year).

[7] This 60-30-10 breakdown Human Resources people throw around as a rough approximation.

[8] This also works great for children: Andrew S. Hanks, David R. Just, and Brian Wansink (2013), “Pre-Ordering School Lunch and Food Choices Encourages Better Food Choices by Children,” JAMA Pediatrics, 167:7, 673-674.

[9] On place to find free posters is from here: wellnessproposals.com/wellness-library/nutrition/nutrition-posters/ and

[10] From Ricky W. Griffin and Gregory Moorhead, Organisational Behaviour: Managing People and Organisations, South Western, 9th Edition, pp. 522-524.

[11] An account of our work can be found here: Cliff Kuang (2012) “In the Cafeteria, Google Gets Healthy,” Fast Company, April 2012.

[12] More at David R. Just and Brian Wansink (2009), “Better School Meals on a Budget: Using Behavioral Economics and Food Psychology to Improve Meal Selection,” Choices, 24:3, 1-6, and at Brian Wansink (2013), “Convenient, Attractive, and Normative: The CANApproach to Making Children Slim by Design, Childhood Obesity, 9:4 (August), 277-278.

[13] The basic study was first shown in James E. Painter, Brian Wansink, and Julie B. Hieggelke (2002), “How Visibility and Convenience Influence Candy Consumption,” Appetite, 38:3 (June), 237-238. The 9% drop was reported by Jennifer Kurkoski and Jessica Wisdom to Cliff Kuang in Fast Company, April 2012.

[14] The general figure our research has discovered is closer to 22% for the average person, but this 32% increase was reported by Jennifer Kurkoski and Jessica Wisdom to Cliff Kuang in Fast Company, April 2012.

[15] This is a great way to eat smaller snacks – eat only ¼ as much and distract yourselve for 15 minutes returning phone calls or straightening up: Ellen Van Kleef, Mitsuru Shimizu, and Brian Wansink (2013), “Just a Bite: Considerably Smaller Snack Portions Satisfy Delayed Hunger and Craving,” Food Quality and Preference, 27:1, 96-100.

[16] A major drawback is that they are very subjective in where the line is drawn – is 1% milk a red light or a yellow light? When consumers think there is too much subjectivity, they either ignore it or react against it.

[17] This is a cool study on lunch trays with unexpected results: Brian Wansink and David R. Just (2014), “Trayless Cafeterias Lead Diners to Take Less Salad and Relatively More Dessert,” Public Health Nutrition, forthcoming.

.

[18] The full list of all of the changes is available at SlimByDesign.org.

[19] Always serve the healthy things first, even at home. Brian Wansink and Aner Tal (2014), “The Power of Healthy Primes When Selecting Meals,” under review.

[20] Here’s the best reason to start at the healthiest part of the buffet line: Brian Wansink and Andrew S. Hanks (2013), “Slim by Design: Serving Healthy Foods First in Buffet Lines Improves Overall Meal Selection,” PLoS One, 8:10, e77055.

[21] One great solution to this is to have cards limited so they can only buy healthy items. More at Brian Wansink, David R. Just and Collin R. Payne (2013), The Behavioral Economics of Healthier School Lunch Payment Systems, under review.

[22] I’ve heard this quote a number of times. Here’s a secondary citation of it: http://www.instantdane.tv/ultimate-fitness-guru-taught-how-to-stay-fit/. This guy is truly a studly “Just do it” inspiration. Check him out on YouTube.

[23] In the beginning, we held Consumer Camp for anyone who had participated in a study of ours over the prior year. When people are in a study, there’s always some of them who want to know the results. Consumer Camp is a much more fun way to tell them what we’ve been doing than sending out a form e-mail. Over the years we’ve had people from 37 different states attend Consumer Camp. We’ve never limited now many people could attend. More information and registration details can be found at foodpsychology.cornell.edu/content/consumer-camp.

[24] The same thing happens even if you ask people to just “think” about exercising. See Werle, Carolina O. C., Brian Wansink, and Collin R. Payne (2011), “’Just Thinking About Exercise Makes Me Serve More Food:’ Physical Activity and Calorie Compensation,” Appetite, 56:2 (April), 332-335.

[25] Described in Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011.

[26] This changed the whole way my Lab has viewed exercise . . . for the better: Carolina O.C. Werle, Brian Wansink, and Collin R. Payne,, “The Effect of Distraction in Sequential Actions: When Fun Exercising Avoids Indulgence,” forthcoming.

[27] The basic design of the weight-loss portion of this was presented at the Experimental Biology conference in 2011: Brian Wansink, Aner Tal, and Mitsuru Shimizu (2011), “The Wichita ‘One-Ton’ Weight Loss Program: Community Weight Loss and the National Mindless Eating Challenge, FASEB Journal, 25:974.2.

[28] Details about the program can be found in the article in the next footnote along with this more general version: Brian Wansink (2010), “From Mindless Eating to Mindlessly Eating Better,” Physiology & Behavior, 100:5, 454-463.

[29] When Mindless Eating was published, we were indulged with calls and emails – maybe 800 a week – asking what would be the one or two biggest changes that a person could make in their life that would make the biggest difference in helping them mindlessly eat less. To help each of these people and not lose our lives, we developed the National Mindless Eating Challenge. We directed these people to a website that asked them eighteen different questions, and based on these questions, we presented them with the three small changes they could make that would cause them to lose weight. Not a lot of weight—just 1 or 2 pounds a month—but they would be doing it without dieting, and the number on the scale would be moving in the right direction.

[30] We focused on those who adhered to at least one change they were given. See more at Kirsikka Kaipaninen, Collin R. Payne, and Brian Wansink (2012), “The Mindless Eating Challenge: Retention, Weight Outcomes, and Barriers for Changes in a Public Web-based Healthy Eating and Weight Loss Program,” Journal of Medical Internet Research, 14:6, e168.

[31] If you work in company wellness, you’ll find this article useful. It shows what you can put in these contracts and what to leave out, Rebecca S. Robbins and Brian Wansink (2014), “Designing Employee Health Contracts to be Slim by Design,” forthcoming.

[32] Although this is an early article on this law, there’s not a lot that’s been reported since then that is of much note: Norimitsu Onishi (2008), “Japan, Seeking Trim Waists, Measures Millions,” New York Times (June 13, 2008).

[33] The exact number reported by the AFP agency is 12.3, but I conservatively rounded up because this strikes me strangely too low for such a disciplined country with such strong social norms. Here’s the details: Jacques Lhuillery (2013) “Breaking the Law, one sushi roll at a time,” AFP, (AFP.com/en/node/804444), January 25, 2013.

[34] This is radical thinking, so it’s surprising so many managers seem to be behind it. Download this article at the Social Science Research Network, Rebecca S. Robbins and Brian Wansink (2014) “Evaluating Managers Based on the Wellness of Their Employees,” forthcoming.