"Nobody goes to a restaurant to start a diet."

- Slim by Design

|

|

Here's What to Do

Help Your Fav Restaurant

| |||||||||||||||

Restaurant Confidential

The Psychology of Eating Out

We can make our home slim by design, but that’s only one place we eat. Half of us eat half our meals in restaurants. We can control our own home, but we can’t control our favorite restaurant, right? Wrong. We can change what we do, and we can ask them to change what they do.

Nobody goes to a restaurant to start a diet--they go there to enjoy themselves. But small changes can let us enjoy ourselves and still eat less without resorting to an alfalfa and yak cheese salad. For instance, take our Restaurant Rule of Two--you can order any entrée you want, but you can only have two additional items with it. That could be an appetizer and piece of bread, or a glass of wine and a dessert, or two pieces of bread – you just can’t have it all. People choose what they want most, they still enjoy themselves, and they report to us that they eat about a quarter less. There are a lot of easy tricks you can use to eat better at restaurants.

Nobody goes to a restaurant to start a diet--they go there to enjoy themselves. But small changes can let us enjoy ourselves and still eat less without resorting to an alfalfa and yak cheese salad. For instance, take our Restaurant Rule of Two--you can order any entrée you want, but you can only have two additional items with it. That could be an appetizer and piece of bread, or a glass of wine and a dessert, or two pieces of bread – you just can’t have it all. People choose what they want most, they still enjoy themselves, and they report to us that they eat about a quarter less. There are a lot of easy tricks you can use to eat better at restaurants.

|

There are also a lot of easy tricks restaurants can do to help you eat better. Why would they bother? It’s simple: They make a lot of money off of you, and that money disappears when you choose to eat somewhere else. You just need to know what to ask for and how to ask them. There’s a one-liner about a waitress in a greasy spoon diner who comes to the table with a full tray of coffee and asks, “Who asked for the coffee in a clean cup?” If we know what to ask our favorite restaurants to do for us, we’re likely to do it. If we don’t ask, we have to be resigned to the dirty cup, or whatever they give us.

|

Remember, restaurants don’t want to make us fat. They want to make money. This may sound crazy, but many of them make less profit when you order $4.95 onion rings than when you order the $4.95 side salad, because it has only 13¢ worth of lettuce in it. [6] They’d love us to order the cheap-as-dirt salad, but all restaurants--whether it’s Fat Boy’s Burgers or the French Maiden’s Delicatessen--have three goals when it comes to us:

1. They want us to eat there and not across the street.

2. They want us to spend a lot on their most profitable foods.

3. They want us to leave happy and to come back often.

1. They want us to eat there and not across the street.

2. They want us to spend a lot on their most profitable foods.

3. They want us to leave happy and to come back often.

If they could order for you, they’d probably start you off with that veggie platter or side salad. There’s a huge profit margin on those foods. But it’s just easier to for them to convince you to buy the standby favorites, like French fries and Buffalo chicken wings.[7] In fact, it would be silly for most restaurants to drop their wings and rings from their menu. It’s what people think they want, so they’re highlighted on the menu, they’re part of a special, and the wait staff pushes them. They appear consistently on the menus of casual dining restaurants so people don’t have an excuse to go across the street.

|

But it’s not the onion rings and French fries that trip us up at our favorite “go to” restaurants. It’s what we do in the first 15 minutes after we get there. It looks like this: We arrive without a reservation, and the hostess seats us wherever’s most convenient. We listen to the specials, and skim the menu until a couple things catch our eye. We then imagine which will taste best, and we proceed to order too much food. While we wait, we tear apart the bread in a way that makes zombies appear well-mannered. After our food arrives and we’ve picked all the meaty, cheesy, saucy portions clean, we languidly consider dessert.

From the moment we set foot in a particular restaurant, each choice adds calories to our once girlish and boyish figures: Where we sit, where our eyes land on the menu, and how we imagine the food will taste all make us eat worse than we otherwise would. But there are easy things you can do to turn this around, and easy things the restaurant can do to help. Unfortunately, even though the shrimp salad makes more profit than Buffalo wings, most restaurants don’t know how to help us order the shrimp salad. Yet the answers are simpler than they might think. They start as soon as we walk in the door. |

Where Should You Sit in a Restaurant if You Don't Want to Overeat?

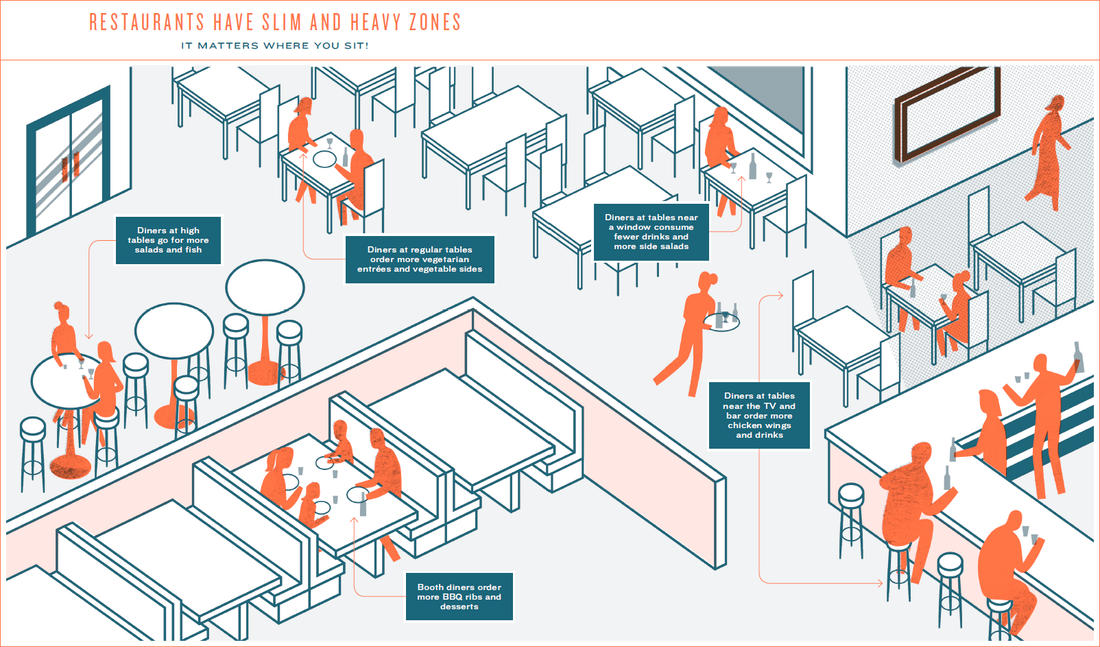

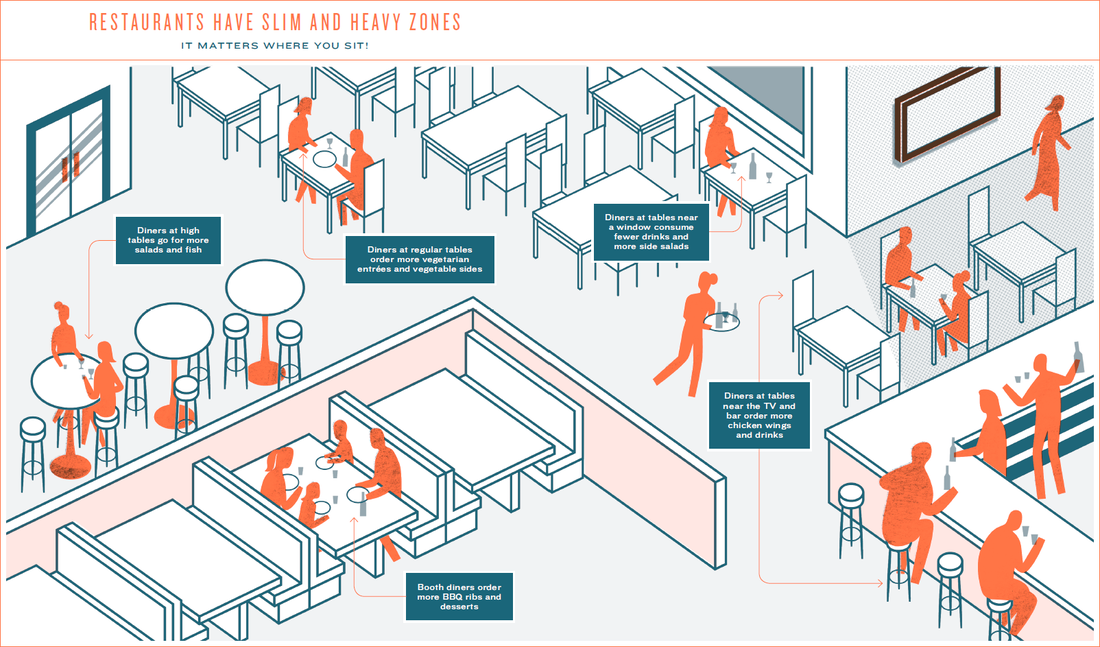

Restaurants number their tables. Table 1 might be closest to the door and Table 91 might be farthest. This makes it easy for your server to keep track of orders. The table number also gets printed on the receipt, which also tells what people ordered, when they ordered, and who their server was. For instance, we might know that Table 91 is a large table in the dark back corner of the restaurant, that Sara served twelve people on April 1, and that everyone ordered fish or chicken. With enough receipts from enough restaurants, we can start to see if where you sit relates to what you eat.

We recently visited twenty-seven restaurants across the country, and we measured and mapped out the layout of each one. We knew how far each table or booth was from the window and front door, whether it was in a secluded or well-traveled area, how light or dark it was, and how far it was from the kitchen, bar, restrooms, and TV sets. After we mapped it out and diners began arriving, we were able to track what they ordered and how it related to where they sat.

Some restaurants we visited for only one or two nights, but at one restaurant we collected every receipt for every day for three straight months. At the end of three months, our Restaurant War Room back in Ithaca, New York, looked like a recycling center. It was full of huge bags stuffed with receipts that were wrinkled or wadded, smeared with steak sauce or wine stains, and autographed with things like “Thanks, Tiffany” and smiley faces. By analyzing these A-1-smeared artifacts, we are able to figure out whether somebody at Table 91 way in back was more likely to order salad or less likely to order an extra drink than somebody at Table 7--which is way up front, next to the door and bar.

Are there fat tables in restaurants? This is a bit preliminary, but so far it looks like people order healthier foods if they sat by a window or in a well-lit part of the restaurant, but they ate heavier food and ordered more of it if they sat at a dark table or booth. People sitting farthest from the front door ate the fewest salads and were 73 percent more likely to order dessert. People sitting within two tables of the bar drank an average of 3 more beers or mixed drinks (per table of four) than those sitting one table farther away. The closer a table was to a TV screen, the more fried food a person bought. People sitting at high top bar tables ordered more salads and fewer desserts.

Some of this makes sense. The darker it is, the more “invisible” you might feel, or the less easy it is to see how much you’re eating. Seeing the sunlight, people, or trees outside might make you more conscious about how you look, might make you think about walking, or might prime a green salad. Sitting next to the bar might make you think it’s more normal to order that second drink, and watching TV might distract you from thinking twice about what you order. If high top bar tables make it harder to slouch or spread out like you could in a booth, they might cause you to feel in control and to order the same way.

Or this could all just be random speculation. Now, the facts are what they are, but why they happen is not always clear.

We recently visited twenty-seven restaurants across the country, and we measured and mapped out the layout of each one. We knew how far each table or booth was from the window and front door, whether it was in a secluded or well-traveled area, how light or dark it was, and how far it was from the kitchen, bar, restrooms, and TV sets. After we mapped it out and diners began arriving, we were able to track what they ordered and how it related to where they sat.

Some restaurants we visited for only one or two nights, but at one restaurant we collected every receipt for every day for three straight months. At the end of three months, our Restaurant War Room back in Ithaca, New York, looked like a recycling center. It was full of huge bags stuffed with receipts that were wrinkled or wadded, smeared with steak sauce or wine stains, and autographed with things like “Thanks, Tiffany” and smiley faces. By analyzing these A-1-smeared artifacts, we are able to figure out whether somebody at Table 91 way in back was more likely to order salad or less likely to order an extra drink than somebody at Table 7--which is way up front, next to the door and bar.

Are there fat tables in restaurants? This is a bit preliminary, but so far it looks like people order healthier foods if they sat by a window or in a well-lit part of the restaurant, but they ate heavier food and ordered more of it if they sat at a dark table or booth. People sitting farthest from the front door ate the fewest salads and were 73 percent more likely to order dessert. People sitting within two tables of the bar drank an average of 3 more beers or mixed drinks (per table of four) than those sitting one table farther away. The closer a table was to a TV screen, the more fried food a person bought. People sitting at high top bar tables ordered more salads and fewer desserts.

Some of this makes sense. The darker it is, the more “invisible” you might feel, or the less easy it is to see how much you’re eating. Seeing the sunlight, people, or trees outside might make you more conscious about how you look, might make you think about walking, or might prime a green salad. Sitting next to the bar might make you think it’s more normal to order that second drink, and watching TV might distract you from thinking twice about what you order. If high top bar tables make it harder to slouch or spread out like you could in a booth, they might cause you to feel in control and to order the same way.

Or this could all just be random speculation. Now, the facts are what they are, but why they happen is not always clear.

Does sitting in a dark, quiet booth in the back of the restaurant make you order more dessert? Not necessarily. It might be that heavy dessert-eaters naturally gravitate to those tables, or that a hostess takes them there out of habit. Regardless, we know that lots of extra calories coagulate where it’s dark and far from the door.

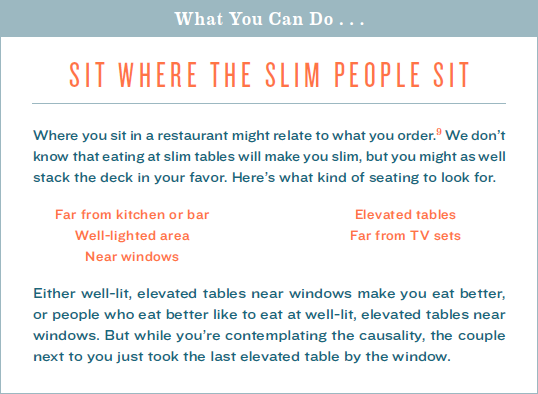

We have an expression in our Lab: “If you want to be skinny, do what skinny people do.” Avoiding the fat tables may be a baby step toward being slim by design. If you want to stack the deck in your favor, think twice about where you sit. Conversely, if a restaurant knows which “skinny tables” will sell more of those high-margin salads and that expensive white wine, they can fill those tables up first, leaving the back tables empty until the onion-ring lovers rise up and demand to be seated.[8]

We have an expression in our Lab: “If you want to be skinny, do what skinny people do.” Avoiding the fat tables may be a baby step toward being slim by design. If you want to stack the deck in your favor, think twice about where you sit. Conversely, if a restaurant knows which “skinny tables” will sell more of those high-margin salads and that expensive white wine, they can fill those tables up first, leaving the back tables empty until the onion-ring lovers rise up and demand to be seated.[8]

How to Read a Menu: Menu Psychology and Menu Engineering

When you’re handed a menu, how do you decide what to order? You probably skim over what’s listed and screen out things you don’t like (the eggplant and puffer fish stir-fry). Then you narrow it down to two or three finalists. You may think you made these choices yourself, but you really didn’t. Your finalists were largely biased by the menu’s layout.

There’s an art and a science to understanding how we read menus. The world’s greatest expert at doing this is my friend Gregg Rapp, an urbane but unassuming man who lives high above Palm Springs in an Architectural Digest-worthy mid-century home that is Frank Sinatra hip. Gregg’s a professional menu engineer. He shows restaurants how to redesign their menus so they guide our eyes to the most profitable items they can sell. But the same principles can be used to help guide our eyes to the healthier foods (which, again, are often the most profitable). Most important, we can use his principles to find hidden healthy treasures and not just settle for the red-boxed, big-type-size listing for the Half-a-Bison Burger we couldn’t ignore.

When it comes to what you order for dinner, two things matter most: What you see on the menu and how you imagine it will taste.

There’s an art and a science to understanding how we read menus. The world’s greatest expert at doing this is my friend Gregg Rapp, an urbane but unassuming man who lives high above Palm Springs in an Architectural Digest-worthy mid-century home that is Frank Sinatra hip. Gregg’s a professional menu engineer. He shows restaurants how to redesign their menus so they guide our eyes to the most profitable items they can sell. But the same principles can be used to help guide our eyes to the healthier foods (which, again, are often the most profitable). Most important, we can use his principles to find hidden healthy treasures and not just settle for the red-boxed, big-type-size listing for the Half-a-Bison Burger we couldn’t ignore.

When it comes to what you order for dinner, two things matter most: What you see on the menu and how you imagine it will taste.

|

1. What you see. We read menus in a Z-shaped pattern. We start in the top left, move to the top right, go to the middle, veer down to the bottom left, and end up on the bottom right. After that, we look at whatever catches our eye--boxes, bold type, pictures, logos, or icons. Basically, any item that looks different is going to get your attention and make you just a little bit more likely to order it. As Gregg says, if the shrimp salad for $8.99 is in a regal-looking burgundy font in a lightly shaded gold box and has a little chef’s hat icon next to it, even Mr. Magoo wouldn’t miss seeing it. He might not buy it, but he’ll consider it. He might remind himself that he had shrimp for lunch or is hungrier for beef, but he might also think, Shrimp salad . . . that sounds good for a change.

Still, it’s a big step from reading the menu to ordering the shrimp salad. What stands in between? Just your imagination. If the words used in the menu lead you to expect this salad will be fresh, flavorful, and filling, you’re a lot closer to ordering it than if they made it sound like fishing bait. |

|

2. How you imagine it will taste. With well-engineered menus, what you see isn’t a coincidence and what you imagineisn’t a coincidence. Your imagination is guided. A great menu guides your imagination to build these expectations so you’re tasting as you’re reading. Again, it leads you to think the shrimp will be “fresh and flavorful” instead of “live bait.” It can be done in two words.

A few years ago, a staid, sleepy place named Bevier Cafeteria wanted to rebrand itself by offering a bunch of healthy new foods. The problem with healthy foods is that most people don’t want them. They want tasty foods--if they happen to be healthy, that’s great but secondary. My buddy Jim Painter and I reviewed the menu and did nothing more than tweak the names of some of the items, adding a descriptive word here or there: red beans and rice became traditional Cajun red beans and rice, seafood fillet became succulent Italian seafood fillet, and so on. Not a single thing changed in the recipes themselves--the only difference was two descriptive words.

Not only did foods with the descriptive names sell 27 percent more, they were rated as tastier than those with the plain boring old names.[13], Not only that, but when people ate a food with an “improved” name, they even liked the cafeteria better--rating it as more trendy and up-to-date.[14] They even rated the chef as having more years of European culinary training. In reality, for all we knew the guy had been fired from Arby’s two months earlier.

And it didn’t even matter how ridiculous the names were. We egregiously renamed chocolate cake as Belgian Black Forest Double-Chocolate Cake. This was nasty, dried-out chocolate sheet cake--really sad stuff. Now it doesn’t even matter that the Black Forest isn’t even in Belgium--when we asked diners what they thought of the cake, some raved about it. One guy went on and on, concluding with, “It reminds me of Antwerp.” Where in Antwerp, I wondered, an abandoned food cart at the train station? Adding a couple words changed sales, tastes, and attitudes toward the restaurant. And it even reminded one person of a delusional vacation.

So what kinds of words do restaurants rely on to help make a satisfied sale? We analyzed 373 desciptive menu items from around the country and found four categories of vivid names:[15]

A few years ago, a staid, sleepy place named Bevier Cafeteria wanted to rebrand itself by offering a bunch of healthy new foods. The problem with healthy foods is that most people don’t want them. They want tasty foods--if they happen to be healthy, that’s great but secondary. My buddy Jim Painter and I reviewed the menu and did nothing more than tweak the names of some of the items, adding a descriptive word here or there: red beans and rice became traditional Cajun red beans and rice, seafood fillet became succulent Italian seafood fillet, and so on. Not a single thing changed in the recipes themselves--the only difference was two descriptive words.

Not only did foods with the descriptive names sell 27 percent more, they were rated as tastier than those with the plain boring old names.[13], Not only that, but when people ate a food with an “improved” name, they even liked the cafeteria better--rating it as more trendy and up-to-date.[14] They even rated the chef as having more years of European culinary training. In reality, for all we knew the guy had been fired from Arby’s two months earlier.

And it didn’t even matter how ridiculous the names were. We egregiously renamed chocolate cake as Belgian Black Forest Double-Chocolate Cake. This was nasty, dried-out chocolate sheet cake--really sad stuff. Now it doesn’t even matter that the Black Forest isn’t even in Belgium--when we asked diners what they thought of the cake, some raved about it. One guy went on and on, concluding with, “It reminds me of Antwerp.” Where in Antwerp, I wondered, an abandoned food cart at the train station? Adding a couple words changed sales, tastes, and attitudes toward the restaurant. And it even reminded one person of a delusional vacation.

So what kinds of words do restaurants rely on to help make a satisfied sale? We analyzed 373 desciptive menu items from around the country and found four categories of vivid names:[15]

|

1. Sensory names: Describing the texture, taste, smell, and mouth feel of the menu item raises our taste expectations. Pastry chefs are the masters of these, using evocative names like Velvety Chocolate Mousse, but a great main menu also has Crisp Snow Peas, Pillowy Handmade Gnocchi, Fork-tender Beef Stew 2. Nostalgic names: Alluding to the past can trigger happy wholesome associations of tradition, family, and national origin. Think Old-style Manicotti, Oktoberfest Red Cabbage, and Grandma’s Chicken Dumplings, or words like Classic or House Favorite. 3. Geographic names: Words that create an image or ideology of a geographic area associated with the food. Think Iowa Farm-raised Pork Chops, Southwestern Tex-Mex Salad, Carolina Mustard Barbecue, or Georgia Peach Tart. 4. Brand names: Cross-promotions are catching on fast in the chain restaurant world. They tell us, “If you love the brand, you’ll love this menu item.” That’s why we can buy Jack Danielsâ BBQ Ribs, and Twixâ Blizzards. For the high-end restaurants, this translates into Niman Ranch pork loin or a Kobe beef kebab. A smart restaurant owner who wants you to eat his healthy, high-margin foods can engineer his menu so that you see them first, and he can describe them so you taste them in your mind. Unfortunately, he could also engineer his menu for evil purposes to guide toward his most profitable unhealthy foods. You can avoid this by decoding some of these seductive names and uncovering the hidden healthy treasures instead. |

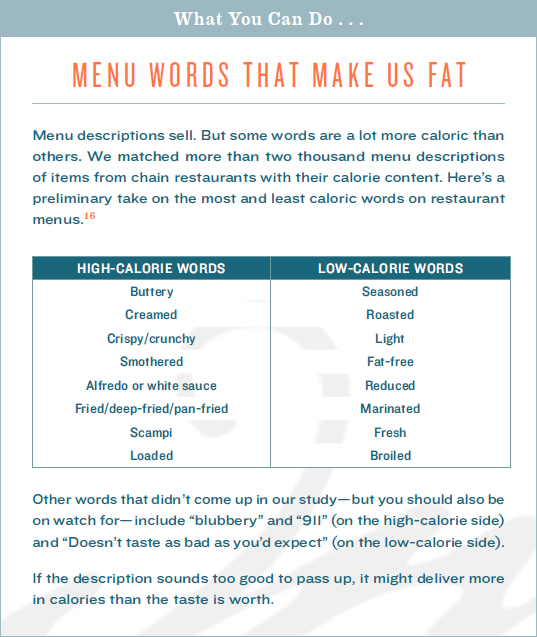

Most non-chain restaurants don’t list their calories, but it’s still pretty easy to break their code and figure out whether their special of the day will make you fit or fat. For the past few months we’ve been tracking the calories on the menus of chain restaurants. Our research is far from complete, but here are some preliminary rules of thumb. On average, if a restaurant put the word “buttery” in the name of a dish, it will have 102 more calories in it. Anything described with the word “crispy” had 131 more calories than its non-“crispy” counterpart.

But just as there are high-calorie words, there are low-calorie words. Order something that is described as seasoned, roasted, or marinated and you won’t be regretting it on the treadmill. These foods had about 60 calories fewer than their non-seasoned, roasted, or marinated counterpart.

But just as there are high-calorie words, there are low-calorie words. Order something that is described as seasoned, roasted, or marinated and you won’t be regretting it on the treadmill. These foods had about 60 calories fewer than their non-seasoned, roasted, or marinated counterpart.

|

If you really want to track down the hidden healthy treasures that might be buried in the middle of the menu, just ask your server, “What are your two or three lighter entrées that get the most compliments?” or “What’s the best thing on the menu if a person wants a light dinner?” If nothing catches your interest, you can always make a request. You can ask if you can get a salad with a skirt steak filet on it, or you can ask for a side of vegetables instead of the fries, or you can ask for the pan-fried fish cooked with Pam instead of oil. More often than not, they’ll make what you want--even huge chains like Red Lobster and Ruby Tuesday often make adjustments. Of course, they could also say, “We’re not going to make what you want,” just as you could say, “And I might not be back.”

|

Why Half-Plate Size Portions are Profitable for Restaurants and Good for Restaurant-Lovers

There’s a Mexican restaurant in the Midwest that boasts “Burritos as Big as Your Head.” If the United Nations had guidelines about what not to eat, this would be in the top three:

1. Don’t eat things on fire.

2. Don’t eat things that are moving.

3. Don’t eat things as big as your head.

Why are restaurant portions so huge? Restaurants think that the more food--the more calories per dollar--they give us, the more likely we’ll eat there and not across the street. But this can backfire if they go too far. When burritos become as big as your head, reasonable people either split one or they don’t buy any side dishes or desserts. Either outcome is bad for the restaurant. They win the Largest Entrée Award but not the Largest Check-size Award.

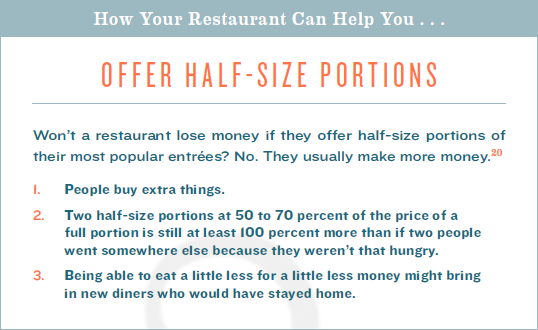

But they could avoid this if they offered some popular entrées in both full and half sizes. Instead of selling 10 ounces of pasta for $10, they could also sell a 5-ounce portion for $5. Yet what restaurant in its right mind would want to sell less food for less money? Only the smart ones. Just as 100-calorie packs meant higher profits and new markets (sweet-tooth dieters) for the snack companies, half-size portions mean the same for restaurants.

Let’s test this out in a truck stop. After all, if it can make it there, it can make it anywhere. Trail’s Family Restaurant is a Minnesota truck stop on I-35 that’s hard to miss because it has a ten-foot-high chainsaw-carved wooden Viking in the lobby. [17][18] It does a solid business--half the customers are local townsfolk and half are truckers and travelers--but Trail's wanted to do better and help their truckers, travelers, and townsfolk eat better.

We started by recommending they offer half-size portions of some popular entrées. They did it, but instead of losing money, they made more. Whereas Lester and Grace would regularly visit the restaurant and split a $10 chicken entrée because “it was big enough for two,” they now each ordered their own half-size version. For twenty years, Lester had quietly let his wife order the chicken breast. Now he could order a half-size steak, and they still had the room to order an appetizer or the $4 salad. Trails also made more money from the people at the table next to them. These people heard about smaller portions and lower prices and figured they’d eat here rather than ordering a flavorless turkey sandwich at the sub shop.

Within three months, more people went to the restaurant, more total entrees were sold, and more people bought side salads. Each month they sold three times as many half-size meals. They also sold 435 more monthly side orders of salad than they did before.[19]

1. Don’t eat things on fire.

2. Don’t eat things that are moving.

3. Don’t eat things as big as your head.

Why are restaurant portions so huge? Restaurants think that the more food--the more calories per dollar--they give us, the more likely we’ll eat there and not across the street. But this can backfire if they go too far. When burritos become as big as your head, reasonable people either split one or they don’t buy any side dishes or desserts. Either outcome is bad for the restaurant. They win the Largest Entrée Award but not the Largest Check-size Award.

But they could avoid this if they offered some popular entrées in both full and half sizes. Instead of selling 10 ounces of pasta for $10, they could also sell a 5-ounce portion for $5. Yet what restaurant in its right mind would want to sell less food for less money? Only the smart ones. Just as 100-calorie packs meant higher profits and new markets (sweet-tooth dieters) for the snack companies, half-size portions mean the same for restaurants.

Let’s test this out in a truck stop. After all, if it can make it there, it can make it anywhere. Trail’s Family Restaurant is a Minnesota truck stop on I-35 that’s hard to miss because it has a ten-foot-high chainsaw-carved wooden Viking in the lobby. [17][18] It does a solid business--half the customers are local townsfolk and half are truckers and travelers--but Trail's wanted to do better and help their truckers, travelers, and townsfolk eat better.

We started by recommending they offer half-size portions of some popular entrées. They did it, but instead of losing money, they made more. Whereas Lester and Grace would regularly visit the restaurant and split a $10 chicken entrée because “it was big enough for two,” they now each ordered their own half-size version. For twenty years, Lester had quietly let his wife order the chicken breast. Now he could order a half-size steak, and they still had the room to order an appetizer or the $4 salad. Trails also made more money from the people at the table next to them. These people heard about smaller portions and lower prices and figured they’d eat here rather than ordering a flavorless turkey sandwich at the sub shop.

Within three months, more people went to the restaurant, more total entrees were sold, and more people bought side salads. Each month they sold three times as many half-size meals. They also sold 435 more monthly side orders of salad than they did before.[19]

|

While offering the half-size portions was only one of a dozen restaurant makeover changes we made at Trail’s Restaurant, it made a big difference. Guest counts increased, sales increased, and check averages increased.[21] Also, for the first time, they won the award for Top Sales of the Year, and they won the award for National Franchise Restaurant of the Year.

Asking our server or the manager for a half-size portion -- or to make it a permanent part of the menu -- is tough for some of us. But it becomes a lot easier for some of us if we think we’re doing them a favor. It might even make them Restaurant of the Year.[22] |

Why Bar Glasses are Getting Taller and Skinnier

Remember the owner of all of those Chinese buffets in chapter 1? When he tossed his 12-inch plates and bought 10-inch ones, other things got smaller, too. People took less food, they wasted less, they ate less, and it cost the restaurant less. The only thing that increased were his profits.

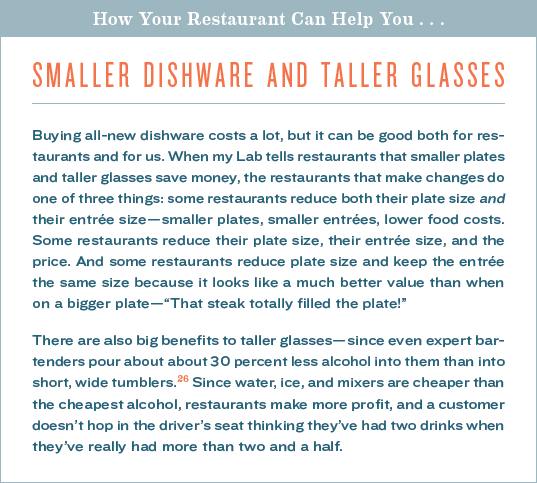

But what if you’re not serving yourself or you don’t own a buffet? Small plates work great for buffets, but they also work for restaurants with table service. Here’s why. That 8-ounce strip steak looks great on the 12-inch plate most restaurants serve it on, but it looks massive on a nice-looking 10-inch plate. It looks like a bigger, better value for the money (“Jeez . . . it filled the whole plate!”). In one study with a favorite colleague of mine, Koert van Ittersum, we found that when we reduced the size of plates, people rated the food as a better value--even when there was 15 percent less food.[23]

It’s the same with glasses. Both their size and shape bias how much we pour and how good of a deal we think it is. When pouring out of a gallon jug, you’ll pour less milk or Red Bull into a small glass than a large one, but you’d also pour less into a tall, thin glass than a short, wide one that holds the same volume. But it’s not just you. The same thing happens to professional pourers--to bartenders.

But what if you’re not serving yourself or you don’t own a buffet? Small plates work great for buffets, but they also work for restaurants with table service. Here’s why. That 8-ounce strip steak looks great on the 12-inch plate most restaurants serve it on, but it looks massive on a nice-looking 10-inch plate. It looks like a bigger, better value for the money (“Jeez . . . it filled the whole plate!”). In one study with a favorite colleague of mine, Koert van Ittersum, we found that when we reduced the size of plates, people rated the food as a better value--even when there was 15 percent less food.[23]

It’s the same with glasses. Both their size and shape bias how much we pour and how good of a deal we think it is. When pouring out of a gallon jug, you’ll pour less milk or Red Bull into a small glass than a large one, but you’d also pour less into a tall, thin glass than a short, wide one that holds the same volume. But it’s not just you. The same thing happens to professional pourers--to bartenders.

|

One winter we visited 86 Philadelphia bartenders--from high-end Rittenhouse Square restaurant lounges with orchids in their windows to low-end West Philly dives with iron bars on their windows. We asked them to pour how much amount alcohol they would use to make a gin and tonic, a whiskey on the rocks, a rum and Coke, and a vodka tonic. It didn’t matter if they had worked there for thirty minutes or thirty years, the typical bartender poured 30 percent more alcohol into short, wide 10-ounce tumblers than into 10-ounce highball glasses. When we showed these bartenders how much they over-poured, they balked, even guffawed. They’re experts--they do this all the time. We asked them to pour again two minutes later. Same result.[24]

If bartenders pour 30 percent too much alcohol into short glasses, it costs the bar money--alcohol is a lot more expensive than tonic, Coke, or ice cubes. That’s bad for the bar, but it’s also bad for you: if you think you’re getting two drinks’ worth of alcohol when you’re really getting closer to three, you might think again about driving. This was important enough for us to take on the road. We contacted the big chains--like Applebee’s, TGI Friday’s, and Olive Garden--and let them know there was an easy way they could make more profit on each drink while also helping their diners get less buzzed. We showed them that regardless of how super awesome their bartenders were and how much training they had, they would always pour 30 percent more alcohol into short, wide tumblers than tall, skinny highball glasses. The easiest solution: use only tall, skinny glasses for most of the drinks, unless somebody insists on a short one. Of course, as they say in This Is Spinal Tap, “It’s a fine line between clever and stupid.”[25] Some of these chains ended up jumping overboard, apparently thinking, “If tall is better than short, then the Super-Duper Tall must be best.” Visit some of these casual dining chains today and you’ll find specialty drinks come in atmospherically tall glasses with ridiculously little in them--they look like two-foot long straws. Though perhaps more stupid than clever, it still works |

|

Making an Entire Town Slim by Design - The Blue Zones Demonstration

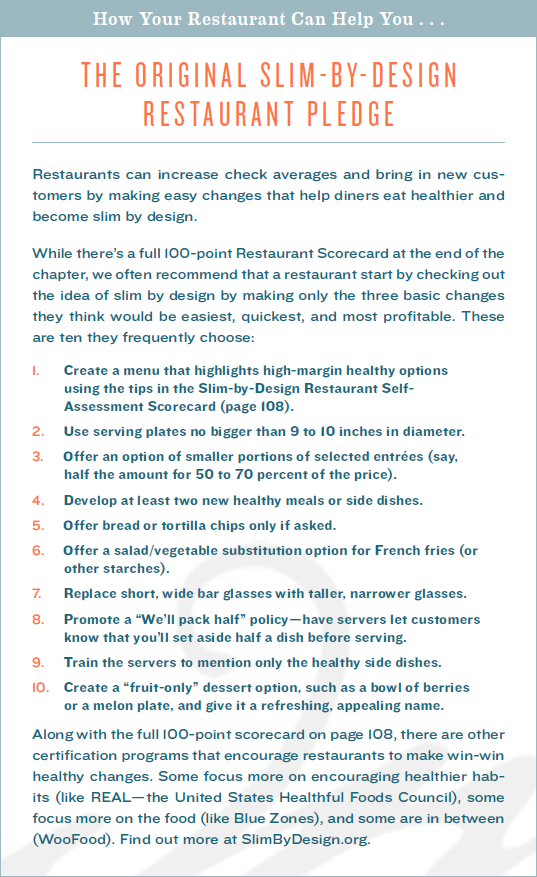

What if a whole town of restaurants agreed to become slim by design? Over the years we’ve advised the big casual dining chains to use smaller plates because it makes the food look bigger, and it makes people eat less and be more satisfied. We’ve advised these same chains and legions of bars to serve drinks in tall, skinny highball glasses instead of short, wide tumblers so that bartenders pour less and drinkers drink less. We’ve helped companies redesign their menus so diners purchase the most healthy and most profitable items. But we hadn’t tried to transform an entire town of restaurants to help lead their diners to be slim by design. One evening in the fall of 2008, I’d have my chance.

I got a call from a soon-to-be-friend named Dan Buettner, a fellow Midwesterner my age who had written Blue Zones, a book on longevity. His plan was to take a small town in Minnesota called Albert Lea and make the townsfolk healthier. He wanted me to come up with an easy checklist of what they could do in their homes, and to also develop a simple plan--a restaurant pledge--that restaurants could use to help people eat better.

At that time I was completing my White House appointment as executive director of the USDA agency in charge of the Dietary Guidelines. When you’re a White House or Presidential appointee, you have the gift of seeing into the future. You know the exact date and time you’re going to be fired: 1:00 PM on the inauguration day of the next president. I told him I’d happily take on his challenge when I returned to Cornell, but that I’d ask restaurants to make only the changes I believed would make them more money. Otherwise the whole plan would fail; no restaurateur can be expected to push healthier choices just because he’s a jolly good fellow.

The rules were as follows: the changes I suggested either had to bring in more customers or increase the check size per customer, and these changes had to lead diners to buy either healthier food or fewer calories. I’d already suggested most of these changes to restaurants when at the USDA, so I knew they worked.

I got a call from a soon-to-be-friend named Dan Buettner, a fellow Midwesterner my age who had written Blue Zones, a book on longevity. His plan was to take a small town in Minnesota called Albert Lea and make the townsfolk healthier. He wanted me to come up with an easy checklist of what they could do in their homes, and to also develop a simple plan--a restaurant pledge--that restaurants could use to help people eat better.

At that time I was completing my White House appointment as executive director of the USDA agency in charge of the Dietary Guidelines. When you’re a White House or Presidential appointee, you have the gift of seeing into the future. You know the exact date and time you’re going to be fired: 1:00 PM on the inauguration day of the next president. I told him I’d happily take on his challenge when I returned to Cornell, but that I’d ask restaurants to make only the changes I believed would make them more money. Otherwise the whole plan would fail; no restaurateur can be expected to push healthier choices just because he’s a jolly good fellow.

The rules were as follows: the changes I suggested either had to bring in more customers or increase the check size per customer, and these changes had to lead diners to buy either healthier food or fewer calories. I’d already suggested most of these changes to restaurants when at the USDA, so I knew they worked.

|

The restaurants in Albert Lea, Minnesota, ranged from an elegant bistros to truck stops, [40] from fast food outlets to fish fry roadhouses. I asked these restaurants to make any three of the changes on the original pledge --whichever they thought would be easiest and most profitable for them. I thought this would be easy, but small towns are small towns. Even though I grew up only 200 miles away in Iowa, they were still pretty suspicious--I was now a geeky, East Coast, Ivy-League professor, and that’s just a little too weird for everyday life.

To overcome their hesitation, I visited their restaurants, helped solve their challenges, drafted up personalized plans for their restaurants, and held small nightly workshops for them. Late in the evening after one workshop, a restaurant owner asked if I had tried some of these slim by design strategies on a local joint called the Nasty Habit. I said I hadn’t heard of it, and four or five of them chuckled among themselves and left. Small towns are small towns. Maybe it’s my imagination, but things seemed to turn around with these restaurants owners. Picturing me eating Fritos for dinner next to a Jägermeister sign might have struck a chord. Some of these restaurant owners might have been initial doubters, but the “pick-and-choose” approach of doing only what they thought would make them money was a juicy selling point. Again, they weren’t doing it for some abstract ideal of having healthier customers; they were doing it to make money. But these restaurants stepped up to the plate--and got the credit and customers they deserved. AARP magazine even called it the Minnesota Miracle. But then that could have been the Jägermeister talking.[41] The restaurant makeover at Albert Lea was a community effort by community leaders to try to get everyone--from restaurants to households--to make just a couple small changes. There’s good news and bad news here. The bad news is that community efforts are a top-down, and they can require mountains of money, tons of time, and lots of tedious meetings. The good news is that you don’t have to wait for a community movement if you focus on your own food radius. All it takes is you. |

Is Your Favorite Restaurant Making You Fat?

Asking a restaurant to start with just three small changes is one way my Lab helped restaurants take baby steps to becoming more profitably Slim by Design. Over the years, our studies have discovered dozens of other changes restaurants can make to profitably help customers eat healthier. They’re profitable because some changes guide people to buy the $10 Shrimp Salad instead of the $6 Onion Rings, others are profitable because they bring in new customers looking for a restaurant that meets their healthy eating needs, and still others are profitable because they keep their loyal customers coming in a little more frequently because they know they won’t have to blow their diets the way they used to.

The 100 top changes that can help you eat healthier are each awarded one point in the Slim by Design Restaurant Scorecard. Although it’s designed for restaurants to use to become healthier and more profitable, you can use it too. It helps you know which of your favorite restaurants will make you slimmer and which will make you fatter. Each of the action items--offering half-size entrée portions, having at least three healthy appetizers, offering bread only if requested, and so on--gets a checkmark and is worth a point. The higher the score, the more your restaurant is nudging you to be slim by design rather than fat by design. But besides helping you evaluate your favorite restaurant, you can also use the scorecard to decide what changes you’d most like them to make. If an unchecked action would help you eat better, ask the manager to make a change to keep you coming back. The worst they can do is say no.

With just a few changes, restaurants can help make you healthier and themselves wealthier. Some changes cost time and money (such as buying smaller plates), but others can be done in a day. But you don’t have to wait for the restaurant to change for you to change. Sit far away from the buffet, ask for a half-price portion or a to-go box, ask them to bring the water and hold the bread--these are mindlessly easy changes that are healthier than leaving things to fate. Think back to the diner waitress who comes to the table with a full tray of coffee and says, “Who asked for the coffee in a clean cup?” We can be the one who asks for our coffee in the clean cup. We can either wait and hope for change, or ask for it.

But the best results happen if restaurants lean in and make changes, too. Ask for the manager, and tell them what changes would make it easier for you to eat better. If you don’t know what to say, you can copy one of the two letters starting on page 000 and either hand it, e-mail it, or text it to them. You could also download a letter from SlimbyDesign.org/Restaurants, change it to suit your personality, and send it.

There’s no one-size-fits-all change for every restaurant owner, and it’s up to them to decide what will work. Chapter 7 shows what tips and strategies you can use to start your own movement. If restaurant owners and managers want our business, they’ll listen. If not, we can always find a new favorite.

The 100 top changes that can help you eat healthier are each awarded one point in the Slim by Design Restaurant Scorecard. Although it’s designed for restaurants to use to become healthier and more profitable, you can use it too. It helps you know which of your favorite restaurants will make you slimmer and which will make you fatter. Each of the action items--offering half-size entrée portions, having at least three healthy appetizers, offering bread only if requested, and so on--gets a checkmark and is worth a point. The higher the score, the more your restaurant is nudging you to be slim by design rather than fat by design. But besides helping you evaluate your favorite restaurant, you can also use the scorecard to decide what changes you’d most like them to make. If an unchecked action would help you eat better, ask the manager to make a change to keep you coming back. The worst they can do is say no.

With just a few changes, restaurants can help make you healthier and themselves wealthier. Some changes cost time and money (such as buying smaller plates), but others can be done in a day. But you don’t have to wait for the restaurant to change for you to change. Sit far away from the buffet, ask for a half-price portion or a to-go box, ask them to bring the water and hold the bread--these are mindlessly easy changes that are healthier than leaving things to fate. Think back to the diner waitress who comes to the table with a full tray of coffee and says, “Who asked for the coffee in a clean cup?” We can be the one who asks for our coffee in the clean cup. We can either wait and hope for change, or ask for it.

But the best results happen if restaurants lean in and make changes, too. Ask for the manager, and tell them what changes would make it easier for you to eat better. If you don’t know what to say, you can copy one of the two letters starting on page 000 and either hand it, e-mail it, or text it to them. You could also download a letter from SlimbyDesign.org/Restaurants, change it to suit your personality, and send it.

There’s no one-size-fits-all change for every restaurant owner, and it’s up to them to decide what will work. Chapter 7 shows what tips and strategies you can use to start your own movement. If restaurant owners and managers want our business, they’ll listen. If not, we can always find a new favorite.

Evidence-based Support and Published References

[1] Our recent survey of wait staff showed they believed only about 18% of their diners asked for to go bags. But it’s getting easier to ask if they want one. Some nicer restaurants will even give you a coat check-style tag you use to you pick up the to-go box at the end of the meal. That way you don’t have an untidy plastic bag of food waiting by your elbow while you finish your coffee.

[2] This is detailed Daniel Kahneman (2011), Thinking: Slow and Fast,” Knopf Books: New York, and also in Dan Ariely’s (2009) “Predictably Irrational” Harper Perienial: New York.

[3] For wine lovers, this is a funny study in chapter 1 of Mindless Eating. This was done in our original research restaurant, which was the Spice Box in Urbana, Illinois, Brian Wansink, Collin R. Payne, and Jill North (2007), “Fine as North Dakota Wine: Sensory Expectations and the Intake of Companion Foods,” Physiology and Behavior, 90:5 (April), 712-16.

[4] Still a working paper: Racheal Behar and Brian Wansink “Would you Take Leftovers? A Test of the Endowment Effect in Restuarants,” Cornell Food and Brand Lab Working Paper Series 2013:13-14.

[5] One example of this is when wine is heavily promoted at such meals: Brian Wansink, Glenn Cordua, Ed Blair, Collin Payne, and Stephanie Geiger (2006), “Wine Promotions in Restaurants: Do Beverage Sales Contribute or Cannibalize?” Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administrative Quarterly, 47:4 (November) 327-36.

[6] A number of managers have told me that after accounting for food costs and labor, there’s less profit in a lot of the low-cost, unhealthy items as there is in a lot of the healthier appetizers, sides, and entrées.

[7] It’s like the parents who say their child eats only macaroni and cheese because they long ago gave up trying to offer the kid anything else.

[8] Of course, if a restaurant sells only chicken wings and onion rings, these same insights can be used to encourage people to overeat. Fortunately, most restaurants would rather make twice as much on a healthy food than make half as much selling anything else.

[9] Still preliminary, Brian Wansink and Mitsuru Shimizu (2014) “Exploring on Seating Location Relates to Restaurant Ordering Patterns, Cornell working paper.

[10] Cool implications for both fast food restaurants as well as for us . . . find the darkest quietest corner to eat! Brian Wansink and Koert van Ittersum (2012), “Fast Food Restaurant Lighting and Music Can Reduce Calorie Intake and Increase Satisfaction,” Psychological Reports, 111:1, 228-232. This study is catchy but has so many limitations, it’s crazy. We don’t know if it was the music or the lighting or whatever that made the biggest difference. The point is that something big happens when you make these changes.

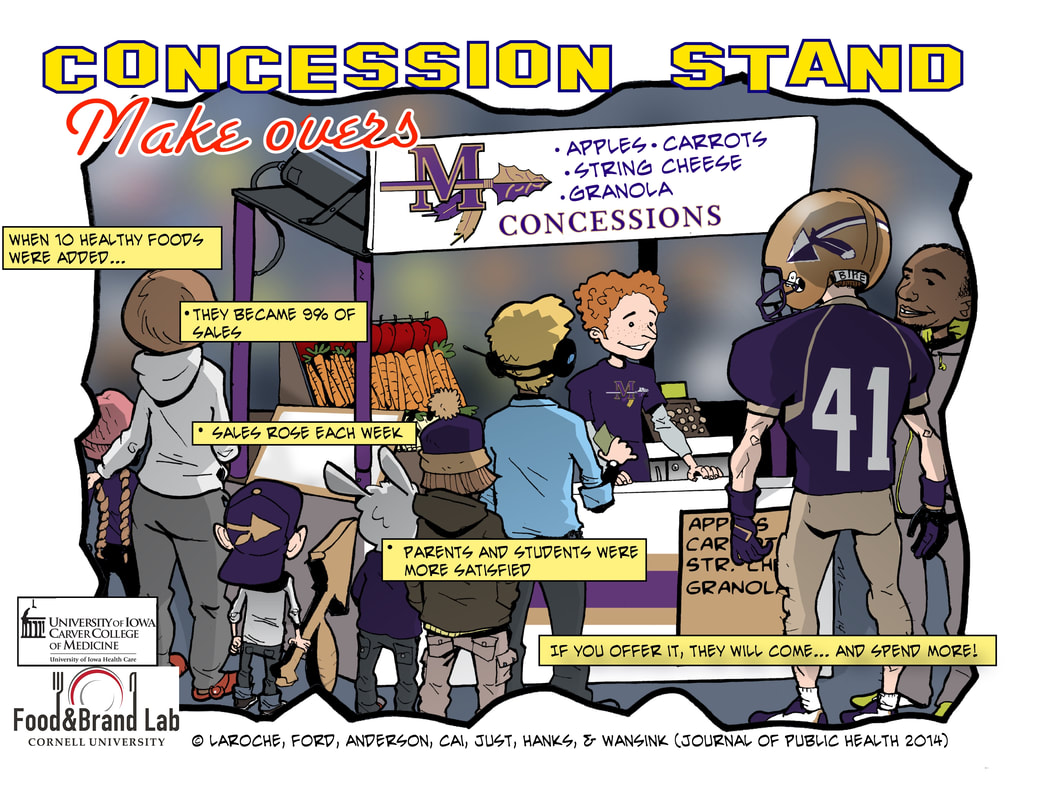

[11] Want to lead a Concession Stand Makeover at your favorite high-school? We’ll tell you how at our website SmarterLunchrooms.org – just search for “Concessions” at that site. In the medical school tradition, this paper has an author list that’s about as long as its whole first paragraph: Helena H. Laroche, Christopher Ford, Kate Anderson, Xueya Cai, David R. Just, Andrew S. Hanks, and Brian Wansink (2013), “Concession Stand Makeovers: A Field Study of Serving Healthy Foods at high School Concession Stands,” forthcoming.

[12] Two big reasons why people were happier: First, we kept the same foods. Second, we added healthier foods. Some people were happy because they could make it a meal and not have to go home or stop somewhere else. Here’s the cast of characters Helena H. Laroche, Christopher Ford, Kate Anderson, David R. Just, Andrew S. Hanks, Kathryn Hoy, and Brian Wansink (2013), “The Ripple of Healthy Changes: Generating Long-term Adherence in Community-based Studies,” forthcoming.

[13] These results inadvertently leaked to restaurant and hospitality industry magazines long before the study was actually published. I was surprised to be giving a talk at a culinary institute in Florence in summer 2003 and see it on a reading list. The official version is Brian Wansink, Koert van Ittersum, and James E. Painter, “How Descriptive Food Names Bias Sensory Perceptions in Restaurants,” Food Quality and Preference (2004), 16:5, 393-400.

[14] There’s jucy detail about this study in Mindless Eating (Chapter 6. The Name Game), but here’s the complete article: focuses on how menu names influence sales and repeat dining intentions. See Brian Wansink, James M. Painter, and Koert van Ittersum, “Descriptive Menu Labels’ Effect on Sales,” Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administrative Quarterly (December 2001), 42:6, 68-72.

[15] BrianWansink, James M. Painter, and Koert van Ittersum, (2001) “Descriptive Menu Labels’ Effect on Sales,” Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administrative Quarterly, 42:6 (December), 68-72.

[16] Brian Wansink and Lizzy Pope (2013),“How Many Calories Is Crispy? An Analysis of Menu Names and Calorie Levels,” working paper.

[17] I did this at a truck stop when adopting my original Restaurant Pledge so it could be borrowed by the Blue Zonesproject. Find more about half-plate profitability in the article Brian Wansink (2012), “Package Size, Portion Size, Serving Size . . . Market Size: The Unconventional Case for Half-Size Servings,” Marketing Science, 31:1, 54-57.

[18] Here’s why half-size portions work. Although the average monthly unit sales of the large-size portions dropped 297 meals per month or 40.9 percent (p<. 001), the average sales of half-size portions went from zero to 949 units per month. Furthermore, the purchase of selected side orders of salad increased 116.5 percent, from 374 units/month to 811 (p<. 001). This resulted in an average estimated sales increase $3474. After subtracting the decrease in full-size meals and adding the new sales from half-size meals and the new sales from side orders, the increase in side orders and the new sales from half-size meals, the net increase in sales was an estimated $6974.

[19] More about half-plate profitability can be found here: Brian Wansink (2012), “Package Size, Portion Size, Serving Size . . . Market Size: The Unconventional Case for Half-Size Servings,” Marketing Science, 31:1, 54-57.

[20] Again, see Brian Wansink (2012), “Package Size, Portion Size, Serving Size . . . Market Size: The Unconventional Case for Half-Size Servings,” Marketing Science, 31:1, 54-57.

[21] From Matt VanVoltenberg, Trail’s Family Restaurant Manager: “Guest counts have increased since we modified our menu based on Brian Wansink’s suggestions to strategically place half-size portions by their full-size option and to purposefully list side choices with the healthiest options first. In addition, sales are up and guess check averages are on the rise.” From the Restaurant Pledge and Starter Kit from Healthyways|Blue Zones.

[22] Follow-up interviews with diners at a similar location indicated that when full-size portions for $10 were offered in a half-size portion for $7, some couples that would have otherwise split a full-size portion now opted for two $7 half-size portions. Other diners reasoned that by spending a bit less on the entrée, they felt more inclined to buy another item they might not have otherwise purchased.

[23] This is truly a win-win tactic for most restauraunts. Others – especially the super high-end ones want to use a large plate as more of a canvas. The other 98% of all restuarants just need a smaller plate: Brian Wansink and Koert van Ittersum (2014), “ Portion Size Me: Plate Size Can Decrease Serving Size, Intake, and Food Waste,” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, forthcoming.

[24] It’s not just bartenders pouring alcohol, it’s us pouring milk, and our kids pouring juice. Brian Wansink and Koert van Ittersum (2003), “Bottoms Up! The Influence of Elongation and Pouring on Consumption Volume, Journal of Consumer Research, 30:3 (December), 455-463.

[25] This punchy difference between clever and stupid is courtesy of Nigel Tufkin, from the ingenious rockumentary spoof, This Is Spinal Tap. It bears repeating because the world is full of people who love to take things to the extreme. This was a witty warning.

[26] It’s amazing on how powerful this is. Brian Wansink and Koert van Ittersum (2005), “Shape of Glass and Amount of Alcohol Poured: Comparative Study of Effect of Practice and Concentration,” BMJ – British Medical Journal, 331:7531 (December 24) 1512-1514.

[27] We did this fun piece of research at Italian restaurants with the help of Larry Lindner. It’s a neat article with a terrible title: Brian Wansink and Lawrence W. Lindner, “Interactions Between Forms of Fat Consumption and Restaurant Bread Consumption,” International Journal of Obesity, (2003), 27:7, 866-868.

[28] Only 40 percent of the people drink water in restaurants, so in California the water conservation policy is to not put it on the table unless someone asks.

[29] It was once thought that if you drank a lot of water before a meal, it would fill you up and you’d take in fewer calories. In general, that doesn’t seem to hold, and the loss is less than believed. Our work with water and the National Mindless Eating Challenge showed that people who were given water-drinking tips and asked to track their weight lost only 1.2 pounds over the course of 3 months in the study. Kaipaninen, Kirsikka, Collin R. Payne, and Brian Wansink (2012), “The Mindless Eating Challenge: Retention, Weight Outcomes, and Barriers for Changes in a Public Web-based Healthy Eating and Weight Loss Program,” Journal of Medical Internet Research, 14:6, 100-113.

[30] In our experience this goes from about 25% requesting it to about 50% accepting it. More in Brian Wansink and Katie Love (2014) “Slim by Design: Menu Strategies for Promoting High-Margin, Healthy Foods, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Managmement, forthcoming

[31] From Mindless Eating, chapter 9.

[32] Happy Meals offer a lot of options. There’s usually a choice of the main food – Chicken McNuggets, a hamburger, or a cheeseburger (about 70 percent get McNuggets). There’s a choice of a side of French fries or apple slices (about 85 percent get French fries). There’s a choice of a drink – soft drink, chocolate milk, or low-fat white milk (about 80 percent get a soft drink).

[33] McDonald’s change in their Happy Meal – adding apple slices, cutting French frie from 240 to 100 calories, and promoting milk – ended up cutting 104 calories out of what kids ordered – an 18 percent. What’s also cool is it even influence what their Mom or Dad ordered – dessert sales dropped from 10.1 percent to 7.9 percent. See Brian Wansink and Andrew S. Hanks (2013), "Happier Meals: How Changes in McDonald’s Happy Meals Altered Food Choices," Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 45:4 (July-August), 45:4S, 39-40 and the full paper: Brian Wansink and Andrew S. Hanks (2013) Do Calorie Reductions in Children’s Meal Combos Lead to Within-meal Calorie Compensation,” under review.

[34] This is tortured area of research. One of the more recent studies on this is certainly not perfect, but I’d rather poke at our own flaws than at somebody else’s: Jessica Wisdom, George Loewenstein, Brian Wansink, and Julie S. Downs (2013), “Calorie Recommendations Fail to Enhance the Impact of Menu Labeling,” American Journal of Public Health, 103:9:1604-1609.

[35] Calorie labeling works a little (like at a Starbucks) for people who are already weight conscious and don’t need a whole lot more prompting. See Brian Wansink and Aner Tal (2014)“Does Calorie Labeling Make Heavy People Heavier?” forthcoming.

[36] There are a ton of reasons that other restaurants aren’t crazy about calorie labeling: menus vary, ingredients and cooks vary, accurate calculations cost money, plus they might scare customers off or lead them to enjoy their experience less. Yet there are some easy ways that both we and our favorite restaurants can get what we want. We want to eat less calories, and they want to make more money. What we can encourage them to do is to only make the changes that they think will make them more popular and more profitable. For instance, they could start with a few favorites and present them on a table tent, insert, or special section, or simply supply it when asked. It’s as simple as a phone call to a local dietician.

[37] This was conducted up at Rich Foods – a frozen food company in Buffalo. Elisa Chan, Brian Wansink, and Robert Kwortnik (2014) “McHealthy: Habit Changing Interventions that Improve Healthy Food Choices,” under review.

[38] I only know this because I was eating breakfast at a Burger King in Taipei, Taiwan, while writing this sidebar and the entrance featured a floor-to-ceiling wall decal stating this and showing the 80 most popular versions.

[39] This is an incredibly easy technique. The article’s short, but about 95% of what you need to know to use it you’ve already read: Brian Wansink, Mitsuru Shimizu, and Guido Camps (2012), “What Would Batman Eat? Priming Children to Make Healthier Fast Food Choices,” Pediatric Obesity, 7:2, 121-123.

[40] Most of these changes we had made earlier in the Trail’s Family Restaurant. We had made a number of suggestions--offering half-size portions, offering healthy side dishes, and reengineering their menu to help people order healthier. Guest counts increased, sales increased, and check averages were on the rise[40] Also, for the first time ever, they were awarded the top National Franchise Restaurant of the Year and the National Franchise Top Sales of the Year.

[41] From the article in AARP Magazine “The Minnesota Miracle: The extraordinary story of how folks in this small town got motivated, got moving, made new friends, and added years to their lives. January/February 2010 Dan Buettner http://www.aarp.org/health/longevity/info-01-2010/minnesota_miracle.html

Some FAQs from Savvy Diners

• Don't restaurants make money by making us fat?

• Where's the healthiest place to sit in a restaurant?

• What's the best way to read a menu so I eat healthy?

• How do menus trick me to order too much and overeat?

• Where's the best tasting food on a menu that's healthy?

• Can the shape and size of glasses make me drunk?

• What about bread -- do I eat more with butter or olive oil?

• Can fast food be healthier and still make a profit?

• Can restaurants be incentivized to be healthier?

• Where's the healthiest place to sit in a restaurant?

• What's the best way to read a menu so I eat healthy?

• How do menus trick me to order too much and overeat?

• Where's the best tasting food on a menu that's healthy?

• Can the shape and size of glasses make me drunk?

• What about bread -- do I eat more with butter or olive oil?

• Can fast food be healthier and still make a profit?

• Can restaurants be incentivized to be healthier?