An Introduction and Overview

(Brian Wansink 12-10-2019)

|

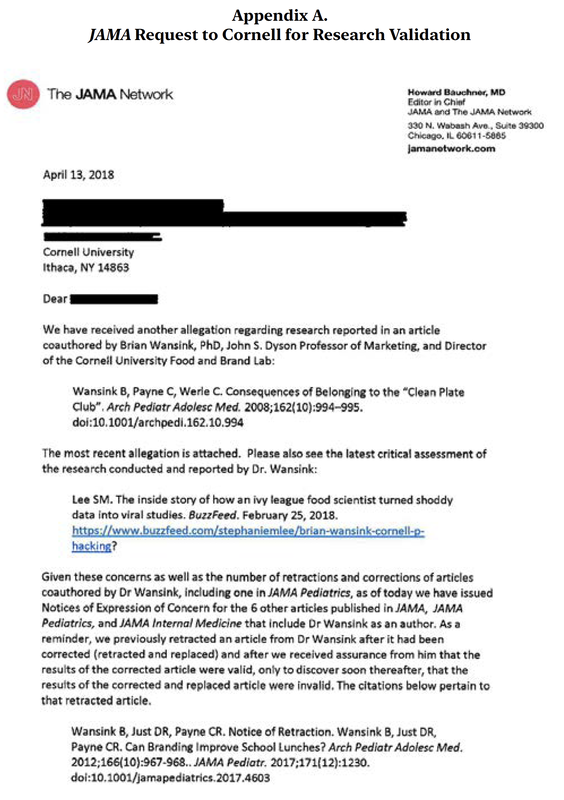

Six of my research articles in JAMA-related journals were retracted in 2018. These retractions offer some useful lessons to scholars, and they also offer some useful next steps to those who want to publish eating behavior research in medical journals or in the social sciences. These six different papers offer some topic-related roadmaps that could be useful. First, they were originally of interest to journals in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) network, and they would probably be of interest to other journals in medicine, behavioral economics, marketing, nutrition, psychology, health, and consumer behavior. Second, they each show what a finished paper might look like. They show the positioning, relevant background research, methodological approach, and relevance to clinical practice or to everyday life. I think all of these topics are interesting and have every-day importance. This document provides a two-page template for each one that shows 1) An overview why it was done, 2) the abstract (or a summary if there was no abstract), 3) the reason it was retracted, 4) how it could be done differently, and 5) promising new research opportunities on the topic. I would strongly encourage anyone who’s interested in publishing in these areas to closely follow the principles of open science. You can start by preregistering hypotheses and planned analyses, and following the other steps along the road to publication. Making specific hypotheses and testing them followed by open science principles will be the best next way forward on these topics.[1] Academia can be a tremendously rewarding career both you and for the people who benefit from you research. Best wishes in moving topics like these forward, and best wishes on a great career. [1] A useful description of these principles can be found at Klein, O., Hardwicke, T. E., Aust, F., Breuer, J., Danielsson, H., Hofelich Mohr, Al, …. Frank, M. C. (2018). A Practical guide for transparency in psychological science. Collabra: Psychology, 4 (1), 20. |

Organization of this WebpageI. The Research Topics

II. Appendices A-C. Investigation into Possible Errors in Six JAMA Papers |

Do Large Serving Bowls Make You to Eat More?

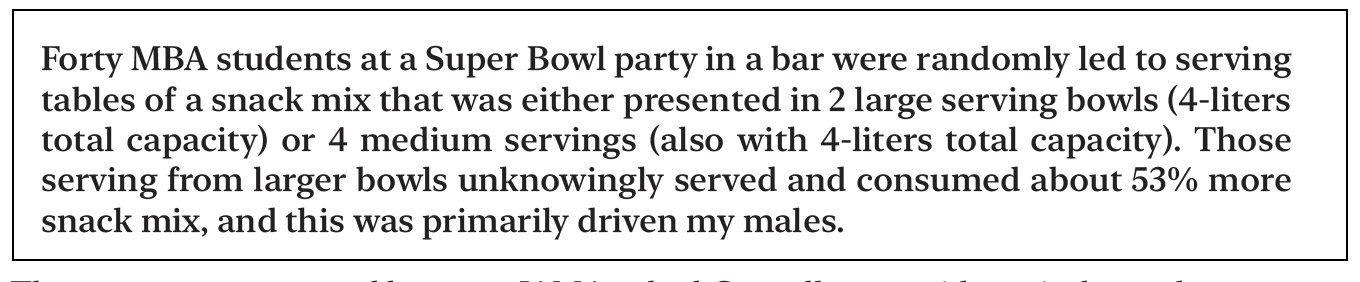

Suppose you’re at a Super Bowl party and you are surrounded by an endless supply of snacks. Will you serve and eat more if the snacks are in large bowls or would you eat more if the same volume of snacks were in twice as many bowls half that size? This has implications for dieters as well as for health conscious and thrifty hosts who don’t want to encourage too much festive overeating.

The Original Findings

The original study was based on a field study involving MBA students at a Super Bowl party in a sports bar in Champaign, IL in 2000. It was published as a two-page research letter in JAMA.[1] Here’s what was found:

The Original Findings

The original study was based on a field study involving MBA students at a Super Bowl party in a sports bar in Champaign, IL in 2000. It was published as a two-page research letter in JAMA.[1] Here’s what was found:

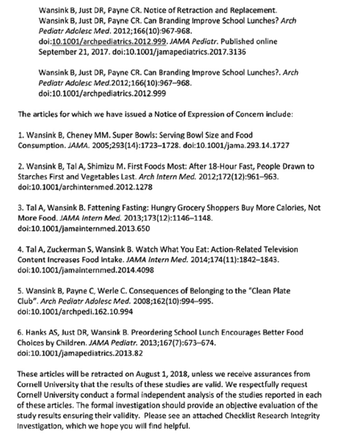

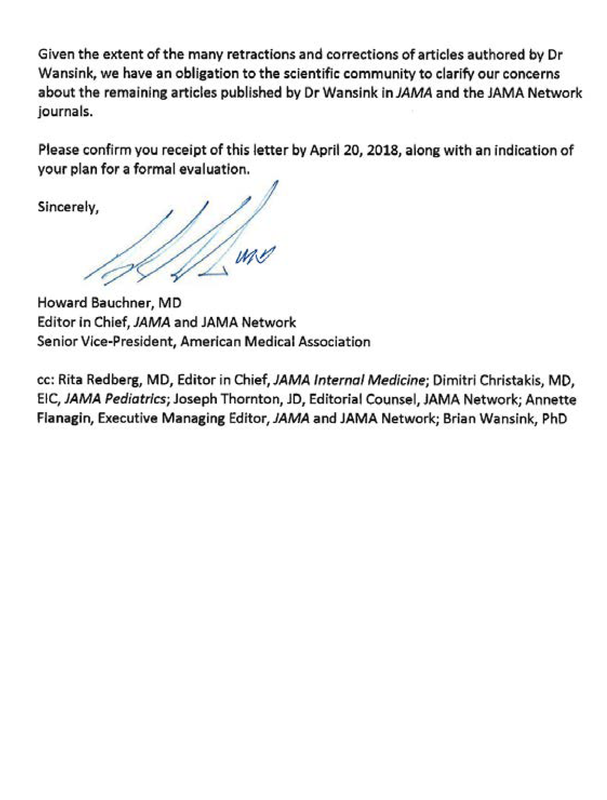

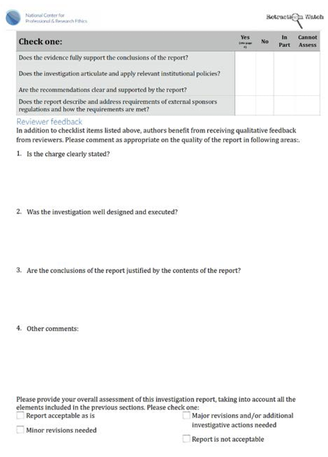

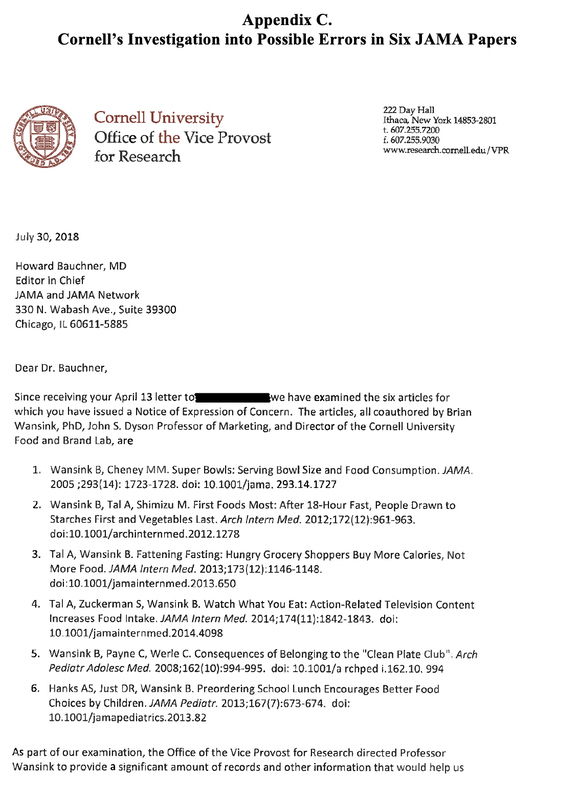

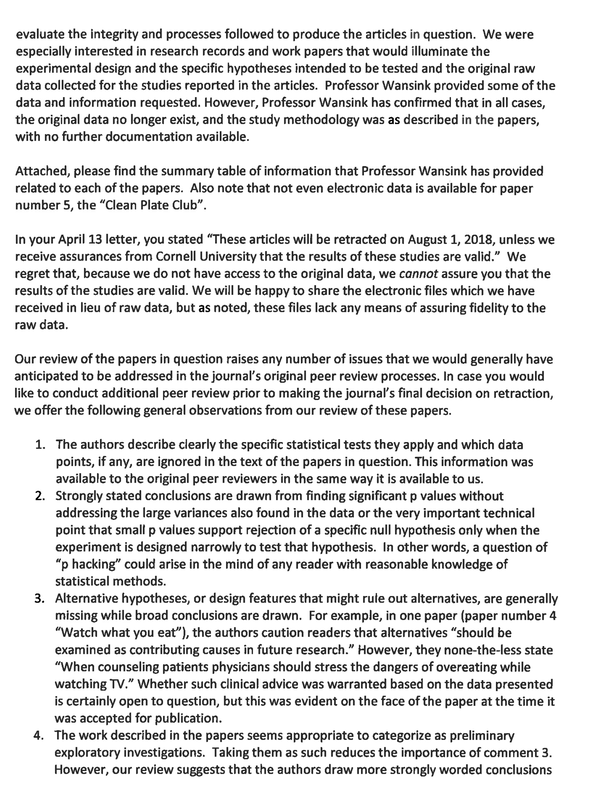

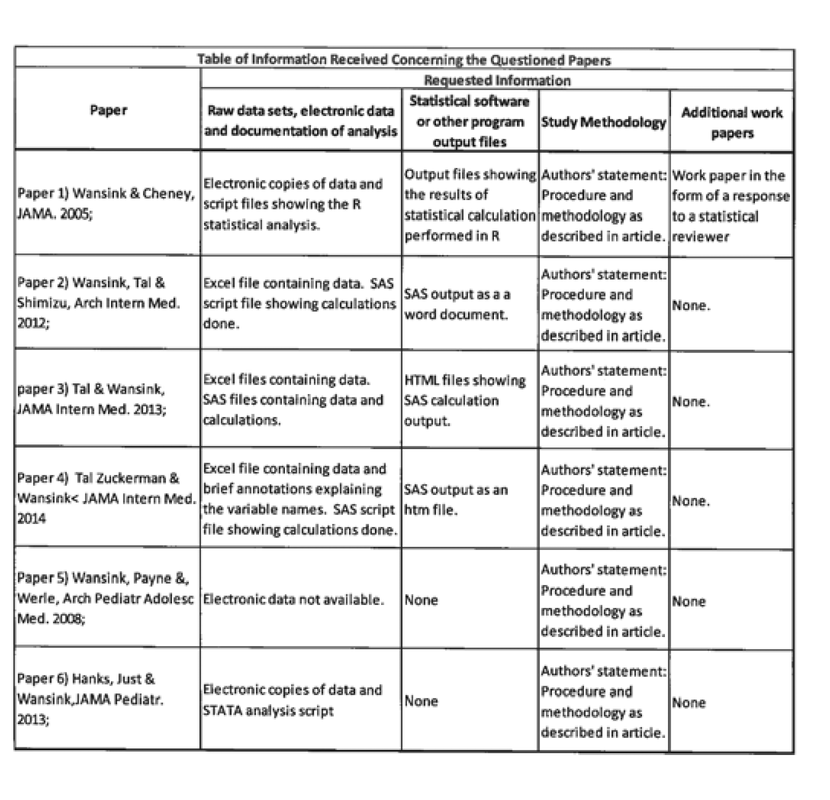

The paper was retracted because JAMA asked Cornell to provide an independent evaluation of this and five other articles to determine whether the results are valid. In their retraction notice, JAMA wrote, “[Cornell’s] response states: ‘We regret that, because we do not have access to the original data [original coding sheets or surveys], we cannot assure you that the results of the studies are valid.’ Therefore, the 6 articles reporting the results of these studies that were published in JAMA Pediatrics, JAMA, and JAMA Internal Medicine, are hereby retracted”[2] (Appendices A-C).

Other Ways to Answer this Question

1. Hypotheses and Extensions: Let’s say that people do eat more from bigger bowls. Do they know they are doing so? One extension of this would be to intercept people after they party was over and ask whether they believe the size of the serving bowl had any impact on how much they served and ate. Causal conversations with people after studies like this surprisingly seem to suggest they don’t think the size of a bowl could influence know much they ate, and even when it’s pointed out, they have alternative rationalizations why they might have eaten more than average (“I was hungry,” “I didn’t eat lunch,” and so forth).

A second interesting extension of follow-up to this would be whether bowl size influences them more if they are in a bad mood or in a good mood. Major sporting events offer an opportunity to do this. Knowing which team, a person is cheering for can be used to see if happy winners celebrate more when given big bowls, or whether unhappy losers drown their sorrows in big buckets.

2. New Methodology Ideas: This particular study was conducted in a noisy sports bar under realistic conditions. Other than being randomly assigned to a serving table and inconspicuously led to that table, everything thing else was natural. Another approach would have been to more tightly test this as a lab study than as a field study in a bar.

As a rough guideline, most of these field studies indicate that people serve and eat around 20% more from larger containers and plates. Seldom more than 30% and seldom less than 10%.

But scholars have also hypothesized that bowl and plate size effects are less strong (or even nonsignificant) when conducted in lab settings, and systematic meta studies have also shown that this effect is much stronger in the field than the lab. Yet what has been missing to date is a very explicit test of a field study versus lab study comparison. An excellent study of this would be useful in resolving some of the effect size differences in these studies.

Summary

Bowl sizes and plate sizes have been a fertile ground for lots of useful studies that have led to new dinnerware lines, changes in hotel and restaurant chain buffet plates, and eating behavior changes among dieters. Things are now at a stage when it would be useful to learn what are the limitations and boundary conditions are around using dinnerware to perceptually change how much is served. Knowing the point at which smaller and smaller dinnerware backfires or the circumstances when it does and doesn’t work will provide a new level of impact.

Additionally, there might be very practical situations where change dishware sizes clashes with a perception of quality or value. It would be important to identify these because they are a different type of boundary condition. For instance, serving a 10-oz steak on a 10-inch plate might make it seem huge compared to when it is served on a 12-inch plate. But is this something a restaurant should do. That is, does it make the steak look like a better value, or does it make it look cheap. Answering these questions would have immediate implications.

[1] Wansink, B; Cheney, MM (13 April 2005). "Super Bowls: serving bowl size and food consumption". JAMA. 293 (14): 1727–8. doi:10.1001/jama.293.14.1727. PMID 15827310.

[2] https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/2703492

Other Ways to Answer this Question

1. Hypotheses and Extensions: Let’s say that people do eat more from bigger bowls. Do they know they are doing so? One extension of this would be to intercept people after they party was over and ask whether they believe the size of the serving bowl had any impact on how much they served and ate. Causal conversations with people after studies like this surprisingly seem to suggest they don’t think the size of a bowl could influence know much they ate, and even when it’s pointed out, they have alternative rationalizations why they might have eaten more than average (“I was hungry,” “I didn’t eat lunch,” and so forth).

A second interesting extension of follow-up to this would be whether bowl size influences them more if they are in a bad mood or in a good mood. Major sporting events offer an opportunity to do this. Knowing which team, a person is cheering for can be used to see if happy winners celebrate more when given big bowls, or whether unhappy losers drown their sorrows in big buckets.

2. New Methodology Ideas: This particular study was conducted in a noisy sports bar under realistic conditions. Other than being randomly assigned to a serving table and inconspicuously led to that table, everything thing else was natural. Another approach would have been to more tightly test this as a lab study than as a field study in a bar.

As a rough guideline, most of these field studies indicate that people serve and eat around 20% more from larger containers and plates. Seldom more than 30% and seldom less than 10%.

But scholars have also hypothesized that bowl and plate size effects are less strong (or even nonsignificant) when conducted in lab settings, and systematic meta studies have also shown that this effect is much stronger in the field than the lab. Yet what has been missing to date is a very explicit test of a field study versus lab study comparison. An excellent study of this would be useful in resolving some of the effect size differences in these studies.

Summary

Bowl sizes and plate sizes have been a fertile ground for lots of useful studies that have led to new dinnerware lines, changes in hotel and restaurant chain buffet plates, and eating behavior changes among dieters. Things are now at a stage when it would be useful to learn what are the limitations and boundary conditions are around using dinnerware to perceptually change how much is served. Knowing the point at which smaller and smaller dinnerware backfires or the circumstances when it does and doesn’t work will provide a new level of impact.

Additionally, there might be very practical situations where change dishware sizes clashes with a perception of quality or value. It would be important to identify these because they are a different type of boundary condition. For instance, serving a 10-oz steak on a 10-inch plate might make it seem huge compared to when it is served on a 12-inch plate. But is this something a restaurant should do. That is, does it make the steak look like a better value, or does it make it look cheap. Answering these questions would have immediate implications.

[1] Wansink, B; Cheney, MM (13 April 2005). "Super Bowls: serving bowl size and food consumption". JAMA. 293 (14): 1727–8. doi:10.1001/jama.293.14.1727. PMID 15827310.

[2] https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/2703492

Do “Clean Plate” Kids Turn into Overeating Adults?

Kids can be really smart. That’s why some of our best ideas as parents back-fire. Take the Clean Plate Club, for example.

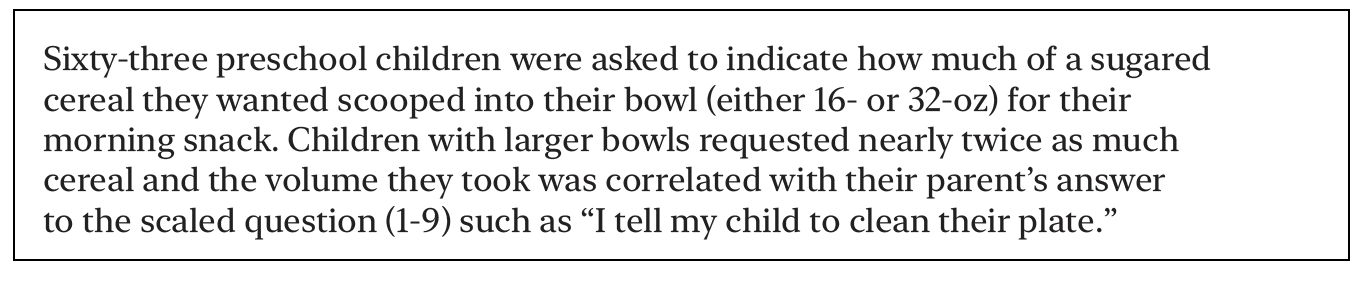

Some parent insist they kids clean their plate. Other parents are more relaxed about it. If a parent regularly insists their child clean their plate, will it alter the amount of food a child decides to serve themselves? Maybe they serve less of new foods because they don’t want to have to eat them if they don’t like them. Or maybe they serve themselves a lot more of the unhealthy and indulgent foods they love because they know that once they get on their plate, they’ll be able to eat them all.

The Original Findings

It was published in 2008 as a two-page letter in the Pediatric Forum of what is now JAMA Pediatrics.[1] It was based on a lab study with preschoolers. There’s no abstract to the paper, but here is what we found.

Some parent insist they kids clean their plate. Other parents are more relaxed about it. If a parent regularly insists their child clean their plate, will it alter the amount of food a child decides to serve themselves? Maybe they serve less of new foods because they don’t want to have to eat them if they don’t like them. Or maybe they serve themselves a lot more of the unhealthy and indulgent foods they love because they know that once they get on their plate, they’ll be able to eat them all.

The Original Findings

It was published in 2008 as a two-page letter in the Pediatric Forum of what is now JAMA Pediatrics.[1] It was based on a lab study with preschoolers. There’s no abstract to the paper, but here is what we found.

The paper was retracted because JAMA asked Cornell to provide an independent evaluation of this and five other articles to determine whether the results are valid. In their retraction notice, JAMA wrote, “[Cornell’s] response states: ‘We regret that, because we do not have access to the original data [original coding sheets or surveys], we cannot assure you that the results of the studies are valid.’ Therefore, the 6 articles reporting the results of these studies that were published in JAMA Pediatrics, JAMA, and JAMA Internal Medicine, are hereby retracted”[2] (Appendix B).

Other Ways to Answer this Question

1. Hypotheses and Extensions: Although a lot of people think they are members of the Clean Plate Club, when this article was first published there wasn’t a lot of research on it. One set of questions that would be promising to explore are those which would examine the long-term consequences be forcing kids to clean their plate. That is, maybe they learn to take smaller portions of healthier foods and larger portions of desserts. Maybe they grown up to be a heavier adult. Maybe they grown up to be less adventurous eaters because they are afraid to try new foods for fear that they would have to finish all of them (just like they did as a child).

2.New Methodology Ideas: Many of the basic questions asked above could be at least preliminarily examined by simply using surveys. It’s not always that compelling, but in an area as under-researched as this, it will give some toeholds for subsequent researchers who want to examine it more causally.

To this end, there can be causal experiments done with children, and the one here represents a gateway into doing so. The idea would be to look for the behaviors that we think kids from Clean Your Plate households would demonstrate compared to those in normal households. After being able to determine what household a child was from, the study would examine how much new foods or how much of a favored food they served themselves and ate when their parents weren’t around. A good place to do this research would be in a daycare setting.

Summary.

The Clean Plate Club is something everyone knows about. Doing more research in this area would have a lot of appeal a lot of immediate applications. Looking at some of the long-term consequences would be great, but in the meantime, there’s a lot of useful insights that could be examined immediately.

[1] Wansink, B; Payne, C; Werle, C (October 2008). "Consequences of belonging to the "clean plate club"". Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 162 (10): 994–5. doi:10.1001/archpedi.162.10.994. PMID 18838655.

[2] https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/2703492

Other Ways to Answer this Question

1. Hypotheses and Extensions: Although a lot of people think they are members of the Clean Plate Club, when this article was first published there wasn’t a lot of research on it. One set of questions that would be promising to explore are those which would examine the long-term consequences be forcing kids to clean their plate. That is, maybe they learn to take smaller portions of healthier foods and larger portions of desserts. Maybe they grown up to be a heavier adult. Maybe they grown up to be less adventurous eaters because they are afraid to try new foods for fear that they would have to finish all of them (just like they did as a child).

2.New Methodology Ideas: Many of the basic questions asked above could be at least preliminarily examined by simply using surveys. It’s not always that compelling, but in an area as under-researched as this, it will give some toeholds for subsequent researchers who want to examine it more causally.

To this end, there can be causal experiments done with children, and the one here represents a gateway into doing so. The idea would be to look for the behaviors that we think kids from Clean Your Plate households would demonstrate compared to those in normal households. After being able to determine what household a child was from, the study would examine how much new foods or how much of a favored food they served themselves and ate when their parents weren’t around. A good place to do this research would be in a daycare setting.

Summary.

The Clean Plate Club is something everyone knows about. Doing more research in this area would have a lot of appeal a lot of immediate applications. Looking at some of the long-term consequences would be great, but in the meantime, there’s a lot of useful insights that could be examined immediately.

[1] Wansink, B; Payne, C; Werle, C (October 2008). "Consequences of belonging to the "clean plate club"". Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 162 (10): 994–5. doi:10.1001/archpedi.162.10.994. PMID 18838655.

[2] https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/2703492

Can Brand Logos Encourage Kids to Eat Heathy Foods?

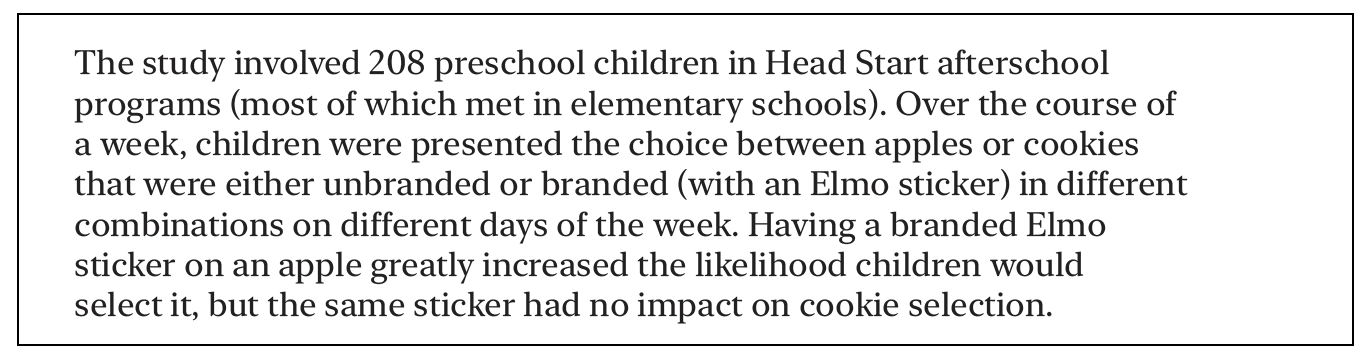

Brand names and logos are used to sell cookies and candy. Can they also be used to sell more fruit by making fruit seem more hip, interesting, or tasty? If so, instead of banning branded products or logos in school cafeterias, it might be better to redirect the branding and logos to the healthier products.

The Original Findings

This 2008 study was published as a two-page research note in what is now JAMA Pediatrics in 2012.[1] It involved a week-long study with Head Start preschoolers. There’s no published abstract, but here is what was found:

The Original Findings

This 2008 study was published as a two-page research note in what is now JAMA Pediatrics in 2012.[1] It involved a week-long study with Head Start preschoolers. There’s no published abstract, but here is what was found:

This paper was retracted because “Following the notice of Retraction and Replacement, the funder of this study informed us of another important error. We had erroneously reported the age group as children ranging from 8 to 11 years old; however, the children were 3 to 5 years old. …

“Given this additional substantial error in reporting the correct ages of the children and the inadequate oversight of the data collection and pervasive errors in the analyses and reporting, the editors have asked that we retract this article. We regret any confusion or inconvenience this has caused the readers and editors of the journal.”[2]

Other Ways to Answer this Question

1.Hypotheses and Extensions: One of the reasons that branding helps increase fruit selection so much more than cookie selection is that most kids naturally love cookies – even without a brand. Therefore, there’s not much higher their likelihood of selection can go. It’s reached a ceiling.

From a nutrition or public health standpoint, one immediate set of studies that could be conducted would be to examine this with different ages of students (toddler, preschool, and elementary students) to see if this is differentially effective at some ages than others. Also, it could be examined whether different types of stickers or logos (familiar vs. unfamiliar; colorful vs. less colorful) are more effective with some ages or genders than with others.

From a psychology standpoint, what would most interesting would be to better understand why we might expect results such as these. Seeing a brand – such as an Elmo logo – on an apple might make a child take it simply because it looks different or curious. But it might make someone take the apple because they think it might taste better than an unbranded apple. If taste expectations can bias real taste experiences, it might even end up being that seeing a brand sticker on a piece of fruit, not only leads more people to take the fruit, but it also makes them think it tastes better.

2.New Methodology Ideas: This study used a within-subject design and although within-subject designs can control for a lot of factors, they also come with another host of problems such as reactivity. This can be especially concerning if the experiment seems too artificial or fake. An opposite approach to this would be to use a between-subject design and to rotate the four different conditions (apple x cookie; branded x unbranded) across these schools. Yet this seems like it would be way too much overkill to answer a fairly simple question. In addition, it potentially suffers from the noise of a bandwagon effect. A child may be more likely to take the same item his friend ahead of him took, regardless of what the food or branded condition was.

An alternative to either might be to rotate conditions within one school and to have children make their selection between the apple and the cookie alone as they came out of the lunch line (or during a break). On one day each week, the combination of choices could be rotated, and the spacing out would probably nullify reactance, but the context would still be very real. Setting up the study in this way would also allow to ask the child a couple quick questions after they selected the item.

Summary.

Over the last few years there have been some promising steps in this direction of trying to brand fruits. McDonald’s use of Cuties Mandarin Oranges is a one example of the promise that smart branding can have for fruit.

In order for this to become more widespread, we can try and imagine what type of research would be most useful in helping inform this trend:

• What ages and gender of kids are most influenced by branding?

• Do colorful but unfamiliar brands or images work just as well as familiar ones?

• Does branding make kids believe the branded food tastes better?

Some of these questions are the ones already noted above. What we need to be mindful that the more realistically our studies are, the more they are likely to be compelling to the people making these decisions to brand healthy foods.

[1] Wansink, Brian; Just, David R.; Payne, Collin R. (1 October 2012). "Can Branding Improve School Lunches?". Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 166 (10): 1–2. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.999. PMID 22911396.

[2] https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/2659568

“Given this additional substantial error in reporting the correct ages of the children and the inadequate oversight of the data collection and pervasive errors in the analyses and reporting, the editors have asked that we retract this article. We regret any confusion or inconvenience this has caused the readers and editors of the journal.”[2]

Other Ways to Answer this Question

1.Hypotheses and Extensions: One of the reasons that branding helps increase fruit selection so much more than cookie selection is that most kids naturally love cookies – even without a brand. Therefore, there’s not much higher their likelihood of selection can go. It’s reached a ceiling.

From a nutrition or public health standpoint, one immediate set of studies that could be conducted would be to examine this with different ages of students (toddler, preschool, and elementary students) to see if this is differentially effective at some ages than others. Also, it could be examined whether different types of stickers or logos (familiar vs. unfamiliar; colorful vs. less colorful) are more effective with some ages or genders than with others.

From a psychology standpoint, what would most interesting would be to better understand why we might expect results such as these. Seeing a brand – such as an Elmo logo – on an apple might make a child take it simply because it looks different or curious. But it might make someone take the apple because they think it might taste better than an unbranded apple. If taste expectations can bias real taste experiences, it might even end up being that seeing a brand sticker on a piece of fruit, not only leads more people to take the fruit, but it also makes them think it tastes better.

2.New Methodology Ideas: This study used a within-subject design and although within-subject designs can control for a lot of factors, they also come with another host of problems such as reactivity. This can be especially concerning if the experiment seems too artificial or fake. An opposite approach to this would be to use a between-subject design and to rotate the four different conditions (apple x cookie; branded x unbranded) across these schools. Yet this seems like it would be way too much overkill to answer a fairly simple question. In addition, it potentially suffers from the noise of a bandwagon effect. A child may be more likely to take the same item his friend ahead of him took, regardless of what the food or branded condition was.

An alternative to either might be to rotate conditions within one school and to have children make their selection between the apple and the cookie alone as they came out of the lunch line (or during a break). On one day each week, the combination of choices could be rotated, and the spacing out would probably nullify reactance, but the context would still be very real. Setting up the study in this way would also allow to ask the child a couple quick questions after they selected the item.

Summary.

Over the last few years there have been some promising steps in this direction of trying to brand fruits. McDonald’s use of Cuties Mandarin Oranges is a one example of the promise that smart branding can have for fruit.

In order for this to become more widespread, we can try and imagine what type of research would be most useful in helping inform this trend:

• What ages and gender of kids are most influenced by branding?

• Do colorful but unfamiliar brands or images work just as well as familiar ones?

• Does branding make kids believe the branded food tastes better?

Some of these questions are the ones already noted above. What we need to be mindful that the more realistically our studies are, the more they are likely to be compelling to the people making these decisions to brand healthy foods.

[1] Wansink, Brian; Just, David R.; Payne, Collin R. (1 October 2012). "Can Branding Improve School Lunches?". Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 166 (10): 1–2. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.999. PMID 22911396.

[2] https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/2659568

Does Preordering Lead to Healthier Lunches?

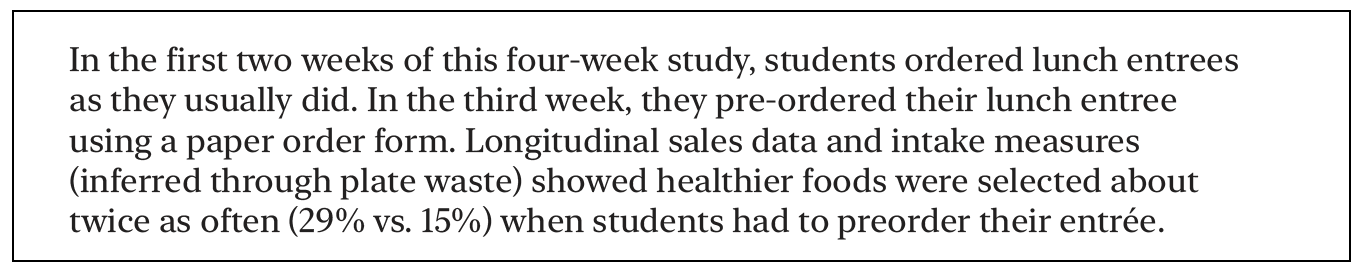

You might heroically plan on eating a healthy salad for lunch, but when noontime rolls around, the French fries will smell too good to pass up. If you had to pre-order your lunch when you first got to work, would you eat better? If so, work cafeterias and school cafeterias could offer a preordering option. This way they could help their employees or students eat healthier and less indulgent lunches.

The Original Findings[1]

The original field research was conducted in a public-school district in the Finger Lakes area of New York. It was published as a two-page research letter, and here’s a summary of the results:

The Original Findings[1]

The original field research was conducted in a public-school district in the Finger Lakes area of New York. It was published as a two-page research letter, and here’s a summary of the results:

The paper was retracted because JAMA asked Cornell to provide an independent evaluation of this and five other articles to determine whether the results are valid. In their retraction notice, JAMA wrote, “[Cornell’s] response states: ‘We regret that, because we do not have access to the original data [original coding sheets or surveys], we cannot assure you that the results of the studies are valid.’ Therefore, the 6 articles reporting the results of these studies that were published in JAMA Pediatrics, JAMA, and JAMA Internal Medicine, are hereby retracted." (See Appendices A-C).

Other Ways to Answer this Question

1. Hypotheses and Extensions: This was a small pilot study that has sizable promise. Two useful extensions would be to a) generalize it to other populations (such as employees in cafeterias), and b) determine if this only works in the short run (like for the first couple weeks) or if it can be sustained past the first three months. Some of our research with other interventions has shown a decay rate of up to 40% over a three-month period unless small variations are made to keep it fresh.

2. New Methodology Ideas: Using a before-after within-subject study would be one approach that eliminates some individual variation. However, it would also need a large control group to not run the risk that something else could influence the results (weather, midterm exams, other menu changes, and so on). One way to solve this problem this would be to split the group in two and reverse the order of the conditions in each group. That is, one group be a control-treatment group (no preordering during month1 but preordering during month2), and the other group be the treatment-control group (pre-ordering in month1 but no preordering in month2).

It would be great to show how preordering influences how many calories kids eat, and how it influences whether the calories they eat vegetable calories or whether they are starch calories. This can be done on an individual level by using the Quarter-plate Method of measuring. Alternatively, if connecting a student’s plate waste with his student ID number is too difficult, this can be recorded in the aggregate. At this stage, knowing if preordering leads to healthier meals is the primary message that would need to communicate to health-minded cafeterias. Answering the follow-up issue of who it influences most can be done with more precision in a follow-up study.

3. Publishing and Outreach Suggestions: A wide range of journals would find different aspects of this interesting in different ways. Here’s two approaches: A) Publish a shorter “Effects” or “Outcome” article in a public health, nutrition, or medical journal, or B) Publish a longer “Process” paper – perhaps with a preceding lab study, and a follow-up study – in a consumer behavior, economics, psychology, or marketing journal. If this is as effective as these earlier studies suggest, I think publishing a shorter piece would get the word out and start getting these changes made in schools and cafeterias sooner rather than later.

Summary

This is a great research question and if the study’s done well, it will have directly relevant implications for whatever is found. There are two keys to making this an influential paper. The first key is to do it in a real cafeteria that is really trying to help people eat healthier. Schools and company cafeterias are two examples, and a hospital cafeteria would also be great. The second key is to set up a pre-ordering intervention that is simple and scalable and not overly complicated or artificial. If simple pre-ordering system is shown to be effective – even if it’s not 100% perfect – it is likely to make a much more compelling point.

[1] Hanks, AS; Just, DR; Wansink, B (July 2013). "Preordering school lunch encourages better food choices by children". JAMA Pediatrics. 167 (7): 673–4. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.82. PMID 23645188.

[2] https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/2703492

Other Ways to Answer this Question

1. Hypotheses and Extensions: This was a small pilot study that has sizable promise. Two useful extensions would be to a) generalize it to other populations (such as employees in cafeterias), and b) determine if this only works in the short run (like for the first couple weeks) or if it can be sustained past the first three months. Some of our research with other interventions has shown a decay rate of up to 40% over a three-month period unless small variations are made to keep it fresh.

2. New Methodology Ideas: Using a before-after within-subject study would be one approach that eliminates some individual variation. However, it would also need a large control group to not run the risk that something else could influence the results (weather, midterm exams, other menu changes, and so on). One way to solve this problem this would be to split the group in two and reverse the order of the conditions in each group. That is, one group be a control-treatment group (no preordering during month1 but preordering during month2), and the other group be the treatment-control group (pre-ordering in month1 but no preordering in month2).

It would be great to show how preordering influences how many calories kids eat, and how it influences whether the calories they eat vegetable calories or whether they are starch calories. This can be done on an individual level by using the Quarter-plate Method of measuring. Alternatively, if connecting a student’s plate waste with his student ID number is too difficult, this can be recorded in the aggregate. At this stage, knowing if preordering leads to healthier meals is the primary message that would need to communicate to health-minded cafeterias. Answering the follow-up issue of who it influences most can be done with more precision in a follow-up study.

3. Publishing and Outreach Suggestions: A wide range of journals would find different aspects of this interesting in different ways. Here’s two approaches: A) Publish a shorter “Effects” or “Outcome” article in a public health, nutrition, or medical journal, or B) Publish a longer “Process” paper – perhaps with a preceding lab study, and a follow-up study – in a consumer behavior, economics, psychology, or marketing journal. If this is as effective as these earlier studies suggest, I think publishing a shorter piece would get the word out and start getting these changes made in schools and cafeterias sooner rather than later.

Summary

This is a great research question and if the study’s done well, it will have directly relevant implications for whatever is found. There are two keys to making this an influential paper. The first key is to do it in a real cafeteria that is really trying to help people eat healthier. Schools and company cafeterias are two examples, and a hospital cafeteria would also be great. The second key is to set up a pre-ordering intervention that is simple and scalable and not overly complicated or artificial. If simple pre-ordering system is shown to be effective – even if it’s not 100% perfect – it is likely to make a much more compelling point.

[1] Hanks, AS; Just, DR; Wansink, B (July 2013). "Preordering school lunch encourages better food choices by children". JAMA Pediatrics. 167 (7): 673–4. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.82. PMID 23645188.

[2] https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/2703492

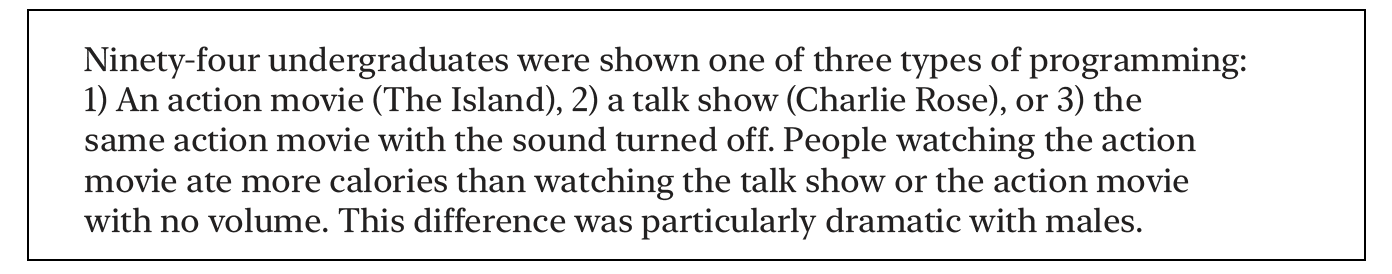

Do Different TV Shows Influence How You Eat?

Eating while watching TV isn’t highly recommended because it’s believed to cause you to eat poorly. If this is indeed true, it could either be because something like TV is distracting or because the pacing and stimulation of it speeds up our eating. For instance, exciting shows with lots of cut scenes or noise might cause us to eat more because it’s really stimulating, or it might cause us to eat less than a boring news show because we are more engrossed and distracted.

If a dieter or food-loving person absolutely believes they must, must, must eat while they watch TV, they might like to know which types of TV shows don’t lead to regretful overeating.

The Original Findings[1]

This research was originally published in 2014 as a two-page research letter in JAMA Internal Medicine. It was based on a lab study conducted with undergraduates in Ithaca, NY. Here’s a summary of the findings:

If a dieter or food-loving person absolutely believes they must, must, must eat while they watch TV, they might like to know which types of TV shows don’t lead to regretful overeating.

The Original Findings[1]

This research was originally published in 2014 as a two-page research letter in JAMA Internal Medicine. It was based on a lab study conducted with undergraduates in Ithaca, NY. Here’s a summary of the findings:

The paper was retracted because JAMA asked Cornell to provide an independent evaluation of this and five other articles to determine whether the results are valid. In their retraction notice, JAMA wrote, “[Cornell’s] response states: ‘We regret that, because we do not have access to the original data [original coding sheets or surveys], we cannot assure you that the results of the studies are valid.’ Therefore, the 6 articles reporting the results of these studies that were published in JAMA Pediatrics, JAMA, and JAMA Internal Medicine, are hereby retracted." (See Appendices A-C).

Other Ways to Answer this Question

1. Hypotheses and Extensions: There are lots of directions to explore how far this could be generalized and what types of foods are most susceptible to being overeaten. As an initial exploration of this, we did this study with small groups of people rather individually, and this raises a number of key extensions. These people had a number of snacks sitting in front of them, and there’s a wide range of ways this could be varied. First, the size and gender composition of the groups could be varied, but it’s not clear what would happen:

• Larger groups may lead people to eat less because they are self-conscious, or they might lead people to eat more if they feel anonymous.

• A mixed gender group might lead women to eat less because they don’t want to be seen as piggish, but it might lead guys to overeat to show they are insatiably macho.

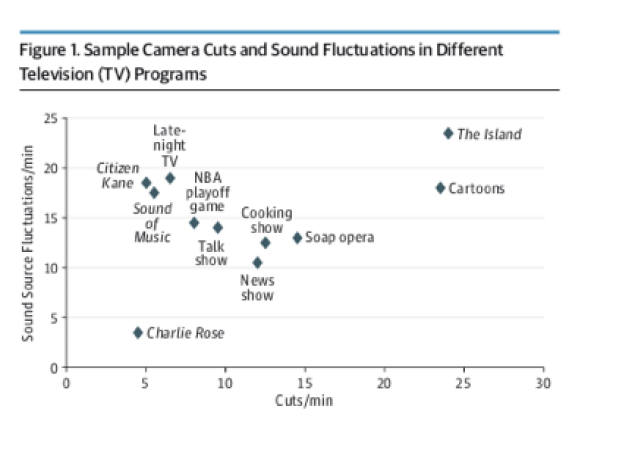

• The study can also be conducted with individually where people watch their own programming, and the programming can then be coded and categorizing based on scene cuts and volume fluctuations. The figure shows how this varies across a wide range of programming:

Second, a researcher could examine how the distance of the food influences how much is eaten. Although the general belief would be that food within arm’s length will be eaten more frequently, we noticed in pilot studies that the farther a person had to reach for food, the more of it they took. Also, food placed in front of where they are sitting might also be eaten more or less often than that on the side since it is more obvious to others that you are taking it.

Furthermore, a useful twist has to do the types of snacks offered. If watching certain types of TV programming leads people to not pay much attention to what or how much they eat, this might be a great way to encourage people to mindlessly eat the boring healthy foods they don’t typically eat – like raw vegetables and fruit. This could be easily tested.

2. New Methodology Ideas: Many of the extensions noted above have different implications for who you recruit, and how you set the viewing environment up. To seem most natural, we arranged the furniture in a manner that was typical for fraternity and sorority TV rooms. This adds realism, but noise. Another way to set them up is to give everyone their own chair.

Summary

Distracting dining is becoming the norm for many people. Preaching snacking abstinence probably won’t work. Instead figuring out how to minimize the damage would be useful. An even better idea is to see if this can be used to turn around snacking in a way that encourages more people to eat healthier snacks instead. If people don’t pay any attention to what they eat as they watch TV, see if anybody notices when you switch a bowl of baby carrots for their bowl of Cheetos.

[1] Tal, A; Zuckerman, S; Wansink, B (November 2014). "Watch what you eat: action-related television content increases food intake". JAMA Internal Medicine. 174 (11): 1842-3. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4098. PMID 25179157.

[2] https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/2703492

Other Ways to Answer this Question

1. Hypotheses and Extensions: There are lots of directions to explore how far this could be generalized and what types of foods are most susceptible to being overeaten. As an initial exploration of this, we did this study with small groups of people rather individually, and this raises a number of key extensions. These people had a number of snacks sitting in front of them, and there’s a wide range of ways this could be varied. First, the size and gender composition of the groups could be varied, but it’s not clear what would happen:

• Larger groups may lead people to eat less because they are self-conscious, or they might lead people to eat more if they feel anonymous.

• A mixed gender group might lead women to eat less because they don’t want to be seen as piggish, but it might lead guys to overeat to show they are insatiably macho.

• The study can also be conducted with individually where people watch their own programming, and the programming can then be coded and categorizing based on scene cuts and volume fluctuations. The figure shows how this varies across a wide range of programming:

Second, a researcher could examine how the distance of the food influences how much is eaten. Although the general belief would be that food within arm’s length will be eaten more frequently, we noticed in pilot studies that the farther a person had to reach for food, the more of it they took. Also, food placed in front of where they are sitting might also be eaten more or less often than that on the side since it is more obvious to others that you are taking it.

Furthermore, a useful twist has to do the types of snacks offered. If watching certain types of TV programming leads people to not pay much attention to what or how much they eat, this might be a great way to encourage people to mindlessly eat the boring healthy foods they don’t typically eat – like raw vegetables and fruit. This could be easily tested.

2. New Methodology Ideas: Many of the extensions noted above have different implications for who you recruit, and how you set the viewing environment up. To seem most natural, we arranged the furniture in a manner that was typical for fraternity and sorority TV rooms. This adds realism, but noise. Another way to set them up is to give everyone their own chair.

Summary

Distracting dining is becoming the norm for many people. Preaching snacking abstinence probably won’t work. Instead figuring out how to minimize the damage would be useful. An even better idea is to see if this can be used to turn around snacking in a way that encourages more people to eat healthier snacks instead. If people don’t pay any attention to what they eat as they watch TV, see if anybody notices when you switch a bowl of baby carrots for their bowl of Cheetos.

[1] Tal, A; Zuckerman, S; Wansink, B (November 2014). "Watch what you eat: action-related television content increases food intake". JAMA Internal Medicine. 174 (11): 1842-3. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4098. PMID 25179157.

[2] https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/2703492