|

We sometimes hear that a child “inherited” their sweet tooth, or their love for vegetables, or for spicy foods from a parent. Although the genetics jury is still out, it is clear that children adopt some of their mother’s tastes when they are still snoozing away in the womb. For instance, pregnant women who drank carrot juice in their last trimester significantly increased how much their children preferred carrot-flavored cereal months later.[i] Not only do they develop prenatal munchie preferences, children also start learning what they like and don’tlike before they are four months old. They do this by picking up on signals a parent or caretaker unconsciously gives about whether a food is tasty or not. This was first discovered in the Massachusetts Reformatory for Women during the 1940s. The women incarcerated here were able to keep children under 3 years of age and to frequently visit them and their carekeepers in the nursery. Records were kept on what the children ate, so it became suspicious when all of a sudden their juice preferences abruptly changed. The psychologist at the reformatory, Sibylle Escalona, began to suspect that the caretakers were unconsciously influencing what the children preferred.[ii] Her report starts out, “It came to attention accidentally that many of the babies under four months of age showed a consistent dislike for either orange or tomato juice.” She then went on to report that babies who had refused to drink orange juice for about three weeks would all of a sudden turn into orange juice lovers within two or three days. She traced these abrupt changes to changes in caretakers. Upon being interviewed, it was found that a couple of the new carekeepers had a strong preference for orange juice and a dislike for tomato juice. Somehow this was passed along to the four month infants. But how? Interestingly, even two-day-old babies are thought to be able to imitate facial expressions of adults.[iii] It could be that these caretakers subconsciously showed subtle signs of acceptance or rejection based upon what they personally felt toward the foods. A fleeting smile or grimace might go a long way toward explaining why one baby has daddy’s sweet tooth and another has mommy’s love for vegetables. This also makes good sense that people feeding babies pretend to taste the food (Mmmm . . . yummy!”) and to open their mouths and play “airplane hanger” when feeding the little tykes.[iv] Escalona’s accidental discovery has aged well. Watching someone smile or grimace when eating food scares elementary children away from even an otherwise tasty food.[v] And this also works with being friendly – you can attract more children to new foods with honey than with vinegar. When a friendly adult repeatedly gave children either canned unsweetened pineapple or cashews, they quickly learned to like this food more than when it was given to them by a less friendly adult.[vi] It is not only our tastes that our children can inherit. It can also be our attitudes about food and eating. In one Yale study of normal weight one-year olds, mothers who were highly preoccupied with weight issues were more likely to be erratic in their behavior during meals. Sometimes, they urged their one-year-olds to eat more, sometimes to eat less, and sometimes they rushed their feedings. They were also much more emotionally aroused when feeding their babies compared to mothers who were not concerned with weight issues.[vii] Children see this anxiety and these food obsessions at a tender tabla rosa age. Just as our children can inherit our eye color and hair color, they might also be behaviorally imprinted with our obsessions with food or with weight. Fortunately, when they start to talk we can even more quickly imprint a passion for balanced meals, smaller portions, vegetables, and fruits.[viii]

References

[i]A good example of the power of availability is Marsha D. Hearn, Tom Baranowski, Janice Baranowski, Colleen Doyle, Matthew Smith, Lillian S. Lin, and Ken Resnicow, “Environmental Influences on Dietary Behavior Among Children: Availability and Accessibility of Fruits and Vegetables Enable Consumption,” Journal of Health Education(1998), vol. 29, pp. 26-32. [i]See Julie A. Mennella and Gary K. Beauchamp, “The Early Development of Human Flavor Preferences,” in Why We Eat What We Eat: The Psychology of Eating, ed. Elizabeth D. Capaldi, Washinton, DC: American Psychological Association, 1996. [ii]This is a classic: Sibylle K. Escalona, “Feeding Disturbances in Very Young Children,” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry(1945) 15:76-80. [iii]T.M. Field, R. Woodson, R. Greenberg, and D. Cohen, “Discrimination and Imitation of Facial Experssions by Neonates,” Science, (1982) 218:179-181. [iv]Thanks to Alexandra Logue for this example from her incredible book, The Psychology of Eating and Drinking, 3rdEdition, (New York: Brunner-Routledge, 2005). [v]F. Baeyens, D. Vansteenwegen, J. De Houwer, and G. Crombex, “Observational Conditioning of Food Valence in Humans,” Appetite,(1996) 27:235-250. [vi]Much of the most interesting research in this area is by LeAnn L. Birch. See, “Generalization of a Modified Food Preference,” Child Development, (1981), 52:755-758. [vii] Pike and Rodin , "Mothers, Daughters and Disordered Eating", Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 1981. [vii] B Wansink, Mindless Eating: Why we eat more than we think, p. 168-171. [xi] Excerpted from the American Dietetic Association’s excellent book, Dieting for Dummies (Wiley, 2004).

1 Comment

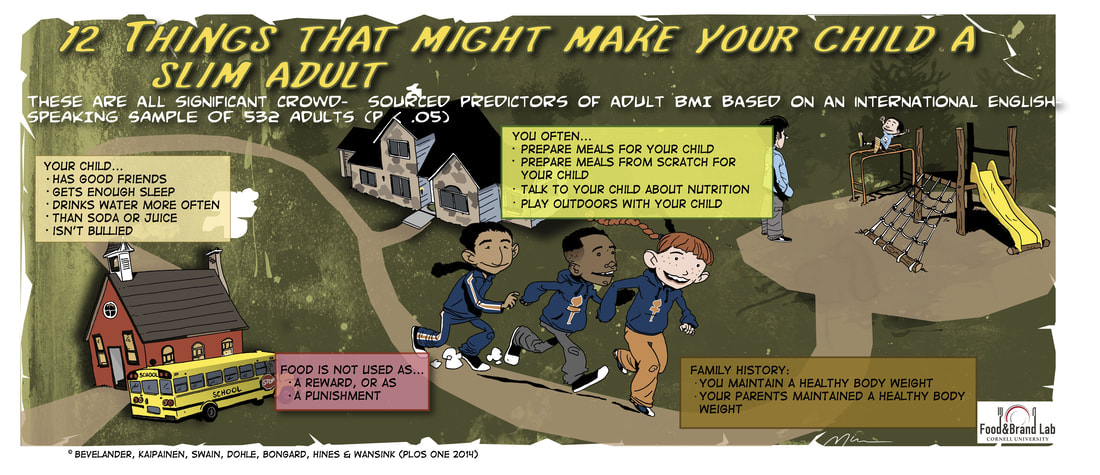

We asked over 500 people from around the world what they believed would predict whether a child would grow up to be overweight. We then used a crowdsourcing approach to see they on target. The infographic below summarizes the key findings. Habits learned and initiated in childhood tend to be continued in adult life, and therefore a stronger focus should be placed on families as a supportive environment for establishing healthy habits. Some Methodology Details.

Participants were recruited through notices posted on reddit.com, a user-generated content news site. Notices were posted in sections focused on dieting, weight loss, and parenting. 532 individuals followed the postings and participated in the study. After entering demographic information, height and weight to calculate body mass index (BMI), and answering at least one question posed by a previous user, participants were asked to enter questions that they felt would help predict the BMIs of other participants. The questions focused on elements of one’s childhood that could predict that same individual’s BMI as an adult. The website predicted each participant’s BMI based on the growing data set. Researchers looked for questions that helped to accurately predict BMI. Of the 59 questions that were posed by the participants and seeded by the researchers, 16 questions were significantly correlated and 3 questions were marginally correlated with BMI. Elements of parenting such as packing school lunches, preparing meals with fresh ingredients, talking with children about nutrition, and engaging in regular outdoor activities were strongly related with having a lower BMI later in life. Unsurprisingly, family history of high BMI was linked to higher BMI in adults; using food as a reward or punishment and restricting food intake were also linked to higher BMI in adults. For better or worse, the nutritional gatekeeper controls around 70% of what our family eats. Children eat what tastes good and what is convenient and what portion size they see as appropriate. You can use this to help create positive lifetime food patterns.

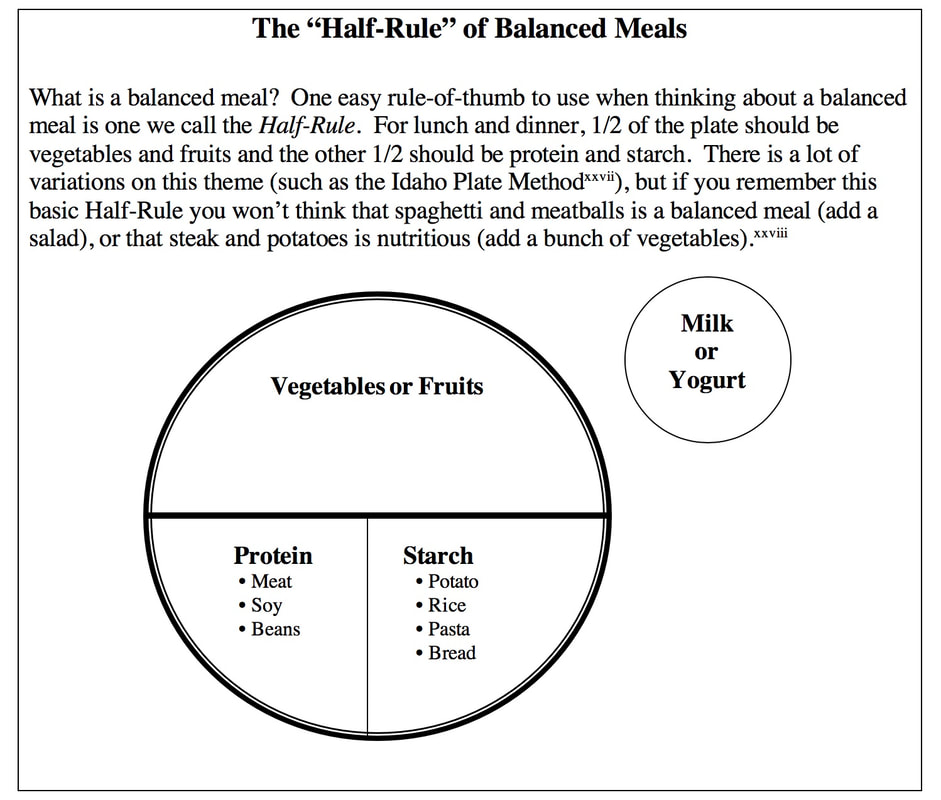

• Be a good marketer. Foods are neither a punishment nor a reward. Healthy foods can, however, be fresh, crunchy, refreshing and make make you strong, smart, and maybe even “goiter-free.” (They might even be what long-neck dinosaurs eat.) Be convincing. Some of our early findings suggest that the more foods you expose your child to, the more nutritionally well-rounded he or she may become. Marketing new recipes, new ingredients, ethnic foods, and different types of restaurants will all help mix it up and break the junk food habit. • Use the Half-Plate Rule. Around the house, the Half-Plate Rule can lead to more balanced meals, and it can give your children an idea of what is a healthy meal. Is spaghetti and meatballs a balanced meal? No, it is only half of the plate – you still need a vegetable or salad for the other half. • Make serving sizes official. Provide “official” servings by giving them their snacks in sealed baggies, in Tupperware, or in Saran Wrap. Do not let them see extra snacks. We found that any extra snacks on the counter increase the amount they see as a serving size. Clean the counter at snack time. The serving-size habits we adapt as children can continue to influence us through our whole lives. This fat-forming transformation in our eating habits happens between the ages of three and five. You can give a three-year-old a lot of food and they will simply eat until they are no longer hungry. They are unaffected by serving size. By age five, however, they will pretty much eat whatever they are given. If they are given a lot, they will eat a lot, and it will even influence their bite-size. This has been vividly shown by LeAnn Birch at Penn State and Jennifer Fisher at the Baylor Medical School.[i] When they gave three- or five-year-old children either medium-size or large-size servings of macaroni and cheese, the three-year-olds ate the same amount regardless of what size they were given. They ate until they were full, and then they stopped. The five-year-olds, rose to the occasion and ate 26% more when given the bigger servings. This is almost the exact same thing that happens to adults. We let the size of a serving influence how much we eat. Serving size is a problem at meal time, but it is also a big problem at snack time. What is a healthy-sized snack? Children tend to think that a serving size is open-ended and up for negotiation – it is pretty much whatever food is available and whatever they can weasel out of their parents. If a candy bar comes in a two ounce package, two ounces must be the correct serving. If the candy bar comes in a four ounce package, four ounces must be the correct serving. How do we adjust serving size to be more reasonable and less negotiable? One tricky way is to influence how much children believe is still available to eat. If they believe plenty of the snack is available, the serving size is whatever they can argue for, cry for, and negotiate. Suppose you make a peanut butter and jelly sandwich as a snack and give them half of it. Is the serving-size half the sandwich? Not if the other half of the sandwich is still sitting on the counter. At that point, a serving includes anything that is left that can be eaten. What happens if you bought raisins in bulk and gave them a quarter cup of them. The same thing. A quarter of a cup is not a serving – a serving can expand to include is whatever’s left that they want to eat. If you buy in bulk to save money, you can use the baggy trick. Remember that none of us really seem to know the amount of a “correct” serving size. We typically look at whatever is wrapped or served and we assume that must be one serving. We can use this notion with our children by giving them their snacks not on a plate, but by putting them in a baggie (or even in a small Tupperware container). In this way, when children get it, they believe it is all they are going to get. There is no more, because this was what was in the container. As long as the extras are out of sight, one serving is whatever they were given. Children look at cues to determine whether they want more to eat. If they think more is available, they can easily think they are still hungry. For instance, in one of our pilot studies, we gave five-year-olds at a day care center six mini-sized cookies in either a zip-lock baggie or on a plate. After they finished the snacks, we asked them if they thought there were any more cookies. Those children who were given cookies on the plate believed that there were more cookies left in the kitchen and they indicated they wanted them. Those children getting the cookies in the baggies were more likely to believe that the cookies were all gone and that snacktime was over. References

[i]Many of these classic studies were conducted at the Child Behavior Labs, when both were at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. LeAnn L. Birch and Jennifer O. Fisher, “Mother's Child-Feeding Practices Influence Daughters' Eating and Weight,” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, (2000), 71, 1054-61. LeAnn L. Birch, Linda McPhee, B. C. Shoba, Lois Steinberg, and Ruth. Krehbiel, “Clean up Your Plate: Effects of Child Feeding Practices on the Conditioning of Meal Size,” Learning and Motivation, (1987), 18, 301-317. See also Barbara J. Rolls, Dianne Engell, and LeAnn L. Birch, “Serving Portion Size Influences 5-Year-Old but Not 3-Year-Old Children's Food Intakes,” (2000), 100, 232-234. Jennifer O. Fisher, Barbara J. Rolls and LeAnne L. Birch, “Children’s Bite Size and Intake of an Entrée are Greater with Large Portions Than with Age-Appropriate or Self-Selected Portions,” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition(2003), 77, 1164-1170. The word “conditioning” conjures up images of food, ringing bells, and Pavolv’s dogs. In the turn-of-the-century pre-Bolshevik Russia, Ivan Pavolv rang a bell and fed dogs frequently enough for them to associate the ringing of the bell with food. Eventually the dogs started to salivate every time they heard the bell – even if there was no food. Eighty years later, psychologist Leann Birch reran this study with a few twists. She and her team repeatedly gave preschool children snacks in a specific location where they would always see a rotating light and hear a certain song. They came to associate the light and the song with snack-time and eating. On a different day shortly after they had finished lunch, she turned on the light and played the song again. Dog-gone it – they started eating again.[i] When we condition our children, we do not do so with lights and music, but with our words and behavior. Take the Popeye Project.[ii]My Lab is trying to understand why some children curiously develop powerfully positive associations with healthy foods – such as broiled fish, broccoli, and even seaweed – that are not typically liked by most children. In beginning this work, we conducted separate interviews with children and with their parents. These interviews took an abrupt right turn a couple weeks after they began. We expected that the children with positive associations toward healthy foods “inherited” them from their parents. While true in some cases, in other cases, the parents did not leave this to chance. These parents explicitly associated the foods with a positive benefit – such as “spinach makes you strong like Popeye.” Some children grew up eating a lot of fish because their parents told them it would make them smart. Others were told to eat lots of carrots so they could see far distances, meat so they would be strong, bananas so they would have strong bones, and fruit so they could keep cool in the summer. A couple children (whose parents were originally from China) even grew up eating – and loving seaweed – because they were told it would prevent “stomach disease” and goiters.[iii] Hard to see that one as a big motivator to a four-year-old. That first day of school would be one to remember, “Hi, I’m Jennifer. What I did on my summer vacation was to go to the beach and eat seaweed so I can be goiter-free.” We’ve interviewed dozens of 3-5 year olds through the Popeye Project so far, and we have collected a lot of insights related to healthy eating. Yet an odd set of interviews occurred in early 2006. At one particular daycare center in Ithaca, NY, a number of the children had uncharacteristically strong preferences for broccoli. This seemed unusual because this bitter vegetable is not as kid-friendly as others (such as carrots and peas). Many of the children loved broccoli because their friends liked it and because it was cool. Most of these associations we could trace back to two brothers. In their laddering interviews both said it reminded them of dinosaur trees, and they liked it because of that. This did not make much sense but because of the far reaching impact it seemed to have on the rest of the daycare we decided to interview their parents. We discovered their mother had convinced them that when they ate broccoli, they could pretend they were “long-neck dinosaurs eating the dinosaur trees.” At the dinosaur-loving age of 2 and 4, that was pretty cool, and it quickly became pretty cool to their friends. Brainwashing, conditioning, or just a smart parent? Viva la Brontosaurus. My Lab tried to leverage this with a vacation Bible School group a short time ago. The children could choose what they wanted from a lunch buffet, but each day we would rename foods to give them better associations. For instance when we renamed peas to “Power Peas,” the number children taking them would nearly double. The most embarrassing poetic license we took was with a V-8-like vegetable juice. We ran out of stock on the days we renamed it “Rainforest Smoothie.” These associations are not wrong although they might be a little stretched – Einstein probably did not make his breakthroughs while eating “brainfood” whitefish at Long John Silvers or the Red Lobster. Nevertheless, just as negative food associations of reward, punishment, comfort, or guilt follow children to adulthood, so can the positive associations of what good food can do for them.[v] But words also work the other way around. Negative associations can be made with unhealthy foods. While we have all heard, “If you eat that, you’ll get fat,” that is not a strong or very vivid form of conditioning. While there are not too many published studies on this, it is an area rich with anecdotes. Joyce is an interesting example. As an adult, she never had cravings for cake and cookies. For 45 years, she has never had to fight the gravitational pull that these sweet snacks have on most of us. Why no apparent sweet tooth? It is almost a Manchurian Candidate brainwashing explanation. As a little girl, her mother repeatedly told her that eating sweet snacks between meals was what low class people did.[vi]Extreme, yes. Bourgeois, yes. Politically incorrect, yes. Yet because there were no sweet snacks available and because she had a (unmerited) stigma attached to them, Joyce never developed the temptation toward these foods that has cursed most of the rest of us. It is not just food availability that drives kiddy consumption, it is also the food conditioning and reinforcement routine set by Mom and Dad. The 4 Ps of Feeding the Finicky An expert who specialized in feeding finicky eaters told me about the 4Ps of feeding the finicky. Positive: Make mealtime a positive experience and praise your kids. Patience: Don’t take food rejection personally Persistence: Keep trying; it might take 15 tastes before tastes begin to change Physical activity: The more they move, the hungrier they will be at mealtime References

[i]We use this book in the field when making child-friendly foods for our studies: Sheila Ellison and Judith Gray,365 Foods Kids Love to Eat: Fun, Nutritious, Kid-Tested and Kid-Approved(New York: Gramercy Books, 1995. [ii]This new area of study is focusing on how why some children develop positive views toward healthy foods, while others do not. The foundation for this is based on what we learned about how comfort foods are formed with adults which is found in Brian Wansink and Cynthia Sangerman, “Engineering Comfort Foods,” American Demographics(July 2000), 66-67. [iii]Both of these children, whose parents were originally from mainland China, were raised almost exlusively on Chinese food. Although iodized salt supposedly supposed to prevent a thyroid condition, this knowledge certainly would not encourage increased seaweed consumption. [iv]This little nugget was from Carolyn Wyman’s very entertaining book, Better than Homemade, (2004, Philadelphia: Quirk Books). [v]Paul Rozin, Nicole Kurzer, and Adam B. Cohen, “Free Associations to “Food”: The Effects of Gender, Generation, and Culture,” Journal of Research in Personality(October 2002), 36:5, 419-441. [vi]This is a common perception in France with snacking. Among the Bourgeois snacking between meals is still considered a behavior well-mannered people do not do. We decided to see if we could track down the mysterious North American Good Cook and get some psychographic snapshots of them and the impact they have. To do this, we surveyed 453 “good cooks” who were considered “way above average” by at least one member of their family. They came from a wide range of ethnicities, income levels, and education levels. Besides being good cooks, the all had one thing in common – they had never attended culinary school. Some learned from a parent or on their own, some cooked out of necessity, and some for fun. We asked them 152 questions about how they cooked, what they cooked, when they cooked, what kind or person they were, what they did in their spare time. Almost everything. We found that although not all good cooks are created equal, 82% of them fit fairly neatly into one of five personality profiles. They could either be classified as Giving Cooks, Competitive Cooks, Healthy Cooks, Methodical Cooks, or Innovative Cooks. All of these cooks – except one – appeared to help their family eat healthier. They all did this largely through the variety of food they served. Serving a wide variety of food can make eating pleasurable and can lead their children and spouse to enjoy a wide range of foods other than the standard, fatty, salty, sweet ones for which we have a natural hankering. Which great cook seemed to have the least positive impact on adult eating habits? Interestingly enough, it was the most common one – the Giving Cook – and they were also the most frequent baker and dessert maker. Although they still put the stamp of variety on their meals, it was in the form of carbohydrates instead of the form of vegetable-heavy cuisine. Does this mean that if you are not a good cook that your children are destined to grow up eating dinners that consist of Dominos Pizza and Cheetos? No, of course not. What it reinforces is that parents can influence the eating habits of their children in either a good way or a bad way. One key take-away for us “not so good cooks” is the good we cando just by adding more variety to our meals. How? These good cooks do it by 1) buying different foods, 2) making different recipes (including different ethnic foods), 3) substituting new ingredients into favorite recipes (mainly vegetables and spices), 4) taking kids to the grocery store and letting them choose a new, healthy food, 5) visit authentic ethnic restaurants. Relevant to the last point, McDonald’s is not a Scottish restaurant. When a child develops a taste for a wide range of foods, healthy foods can be more easily substituted for the less healthy ones. The more he or she will develop a taste for something other than pizza, French fries, candy, and Juicy-Juice. They still may not learn to lovebroccoli, but they will be more willing to eat it occasionally for dinner or with a low calorie ranch dressing as a snack.[i] ---- Picky eater at home? Take heart. Gentle persistence will be rewarded. One taste does not change a person. Professor LeAnn Birch suggests that this can take up to 15 one-bite attempts, but most children end up eventually coming around to liking more than just French fries, ice cream, and Jell-o. Lessons from the Great Cook Next Door All cooks influence their families more than they realize, but great cooks seem to be able to turn children into healthier eaters. What is a great cook look like? A study of 453 great cooks, showed that most of them tend to fall into one of five basic groups:[i] • Giving Cooks (22%). Friendly, well-liked, enthusiastic cooks who specialize on comfort foods for family gatherings and large parties. Giving cooks seldom experiment with new dishes, instead relying on traditional favorites. The only fault of the Giving Cook is they also tend to provide too many home-baked goodies for their family. • Healthy Cooks (20%). Optimistic, book-loving, nature enthusiasts who are most likely to experiment with fish and with fresh ingredients, including herbs. • Innovative Cooks (19%). The most creative, trend-setting of all cooks. They seldom us recipes, they experiment with ingredients, cuisine styles, and cooking methods. • Methodical Cooks (18%).Often weekend hobbyists who are talented, but who rely heavily on recipes. Although somewhat inefficient in the kitchen, their creations always look exactly like the picture in the cookbook. • Competitive Cooks (13%). The Iron Chef of the neighborhood. Competitive cooks are dominant personalities who cook in order to impress others. These are perfectionists who are intense in both their cooking and entertaining. Do not fit into one of these categories? No worries. Find the cooking personality that best resembles you or that you most aspire to be. Then simply try to cook at home. The key is in your habits – your shopping habits, cooking habits, and eating habits. Learn that they do not sell toast in the grocery store. Learn the recipe for boiled water. Then simply give your children a wide varied diet and reasonable serving sizes. The food does not have to be great – just varied and reasonably sized.

[i] See Brian Wansink, “Profiling Nutritional Gatekeepers: Three Methods for Differentiating Influential Cooks,” Food Quality and Preference(June 2003), 14:4, 289-297. In most households, the decision of what to eat for breakfast, lunch, dinner, and snacks is determined by what foods the grocery shopper – the nutrition gatekeeper – purchases. Suppose a teenager wants to eat Pop-tarts, but there are not any in the house. The gatekeeper has de facto decided they won’t be on the menu. This poor Pop-tart hungry kid would have to make a special trip to the grocery store, or start a campaign to put them at the top of the next shopping list. The convenience rule suggests that most of them won’t bother.

On a steamy Manilla-like August day in Washington DC, I met with 800 dieticians and nurses at the American Associations of Diabetes Educators. These people are paid to know how people shouldeat and how they doeat. They deal with the power of dietary influences day in and day out. I asked them about the Nutritional Gatekeeper, the person who does most the shopping and cooking in a household (92% of the time this is the same person). I asked them to estimate what percentage of the food eaten by their family – snacks, meals, out-of-the-house meals, everything – did they control. Their answers surprised me. They estimated that the Gatekeeper controlled an average of 71% of the food decisions of their children and spouse.[i] Not only did they buy everything that was eaten at home, they also made their children’s lunches or gave them enough money to afford whatever lunch or snack they wanted. They even nudged the family restaurant orders by what they recommended or ordered themselves. We have asked over 2000 to estimate this percentage. Some are 10 points lower or 10 points higher, but its always in this range. One group, however, stood out because their estimates were so high. These were people who also rated themselves as good cooks. This makes some sense. It is in line with a study we did that showed that many veggie lovers[ii]claimed to either be a good cook, live with a good cook, or to have had a parent who was a good cook.[iii] [i]Whereas the dieticians estimate 72%, people in the general population generally range from 60-70%. It is a high number. For the details see Wansink, Brian and Collin R. Payne 2006, “Mindless Eating and Estimations: Reported Food Decisions in the Household,” under review Psychological Reports. |

The Mission:For 30 years my Lab and I have focused on discovering secret answers to help people live better lives. Some of these relate to health and happiness (and often to food). Please share whatever you find useful.

Blog Categories

All

|

||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed