|

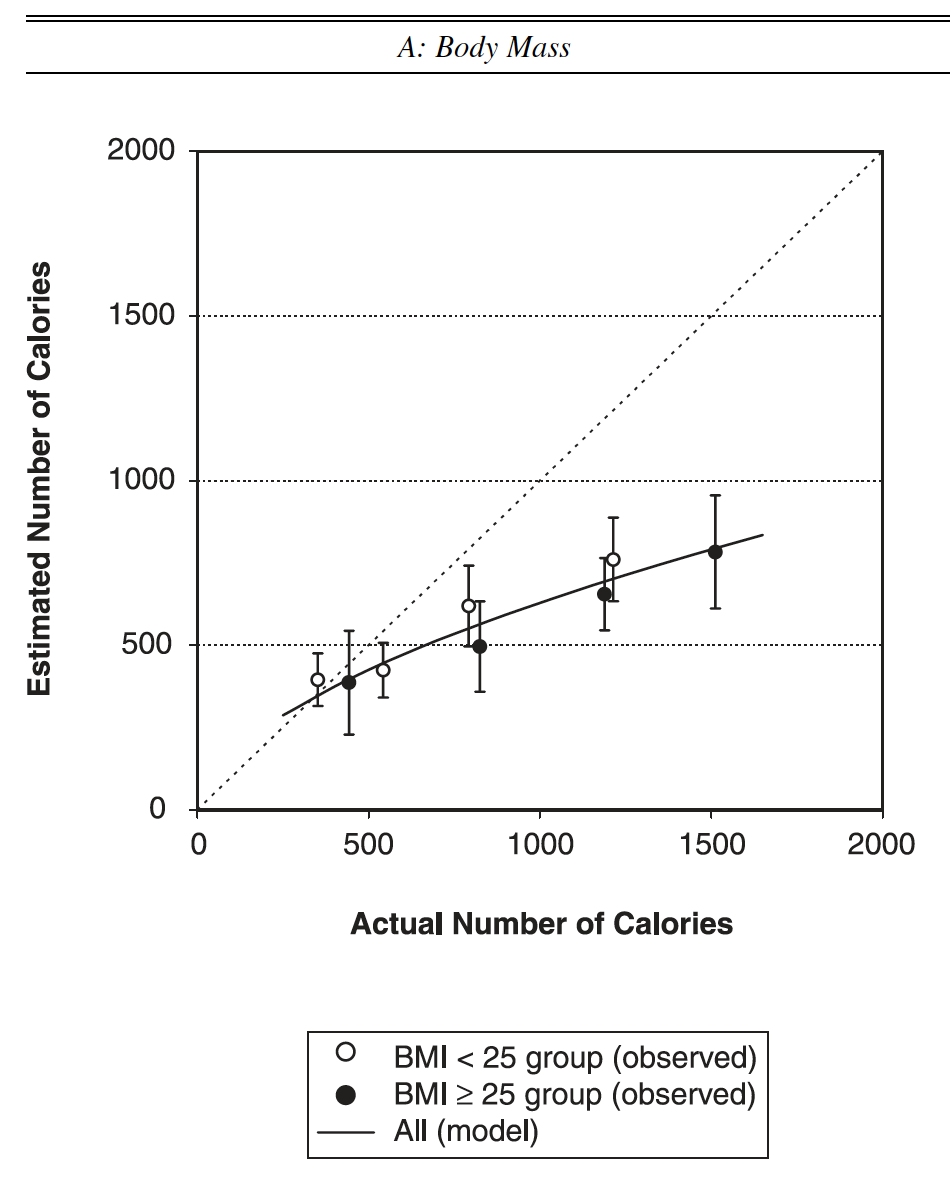

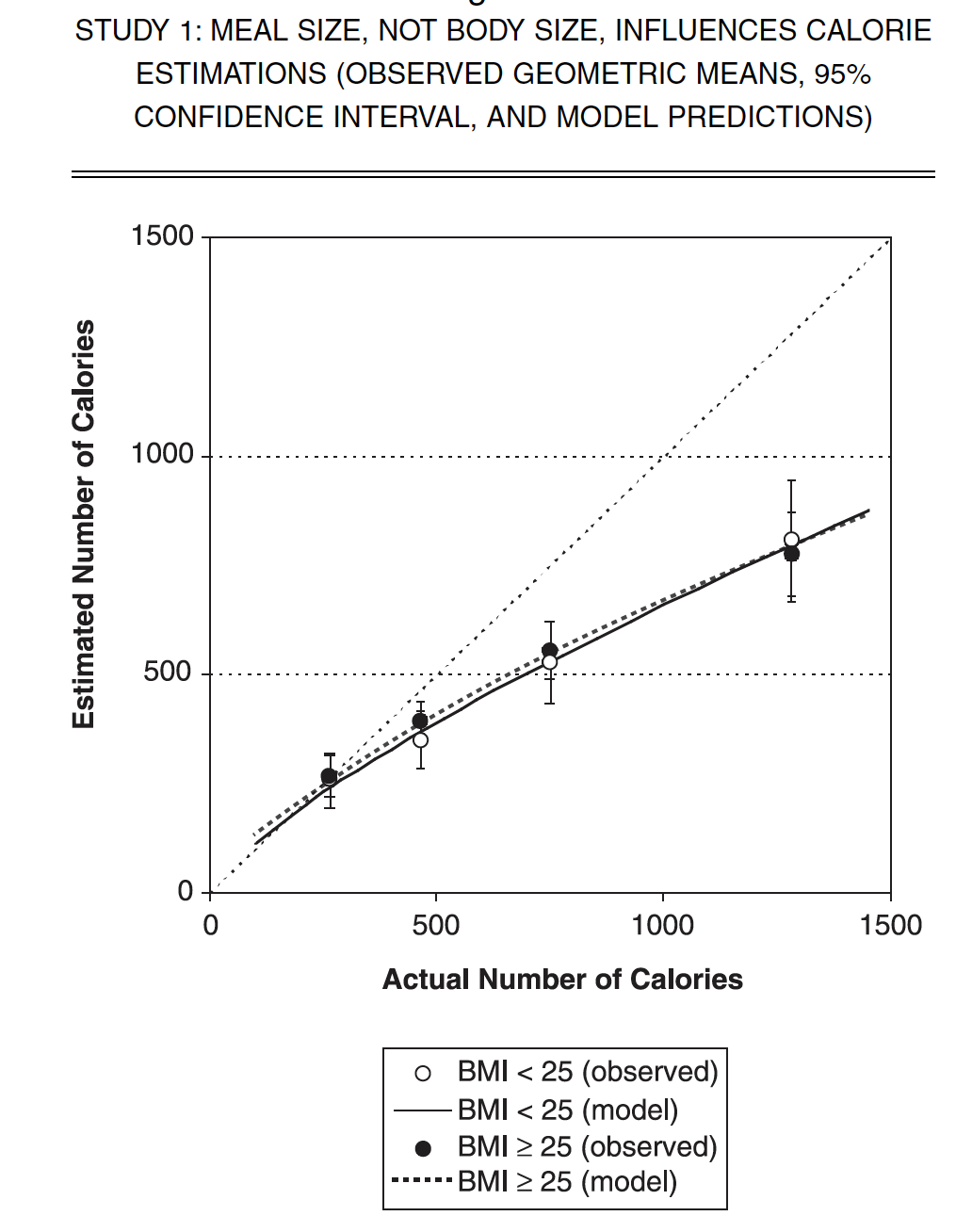

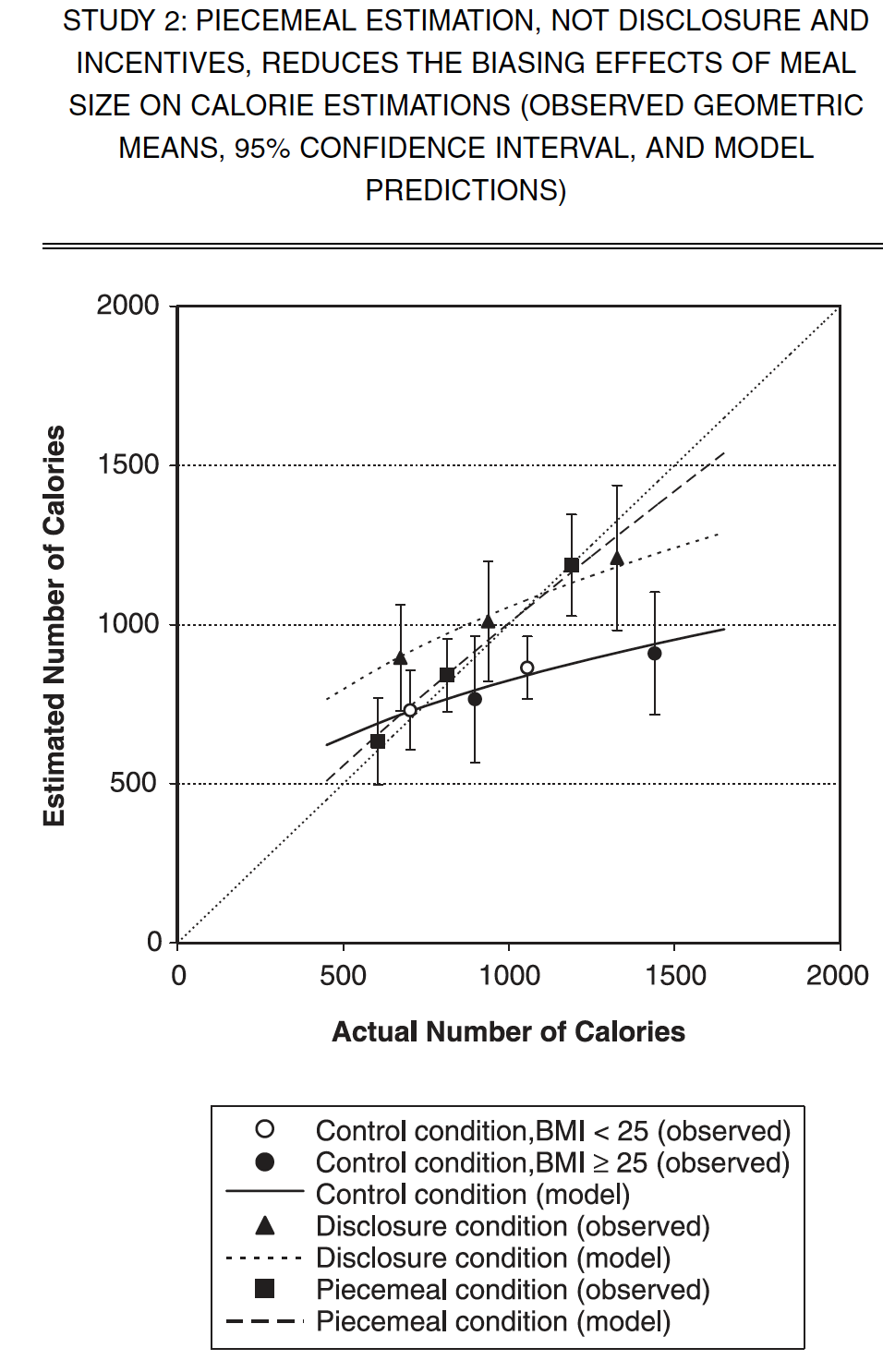

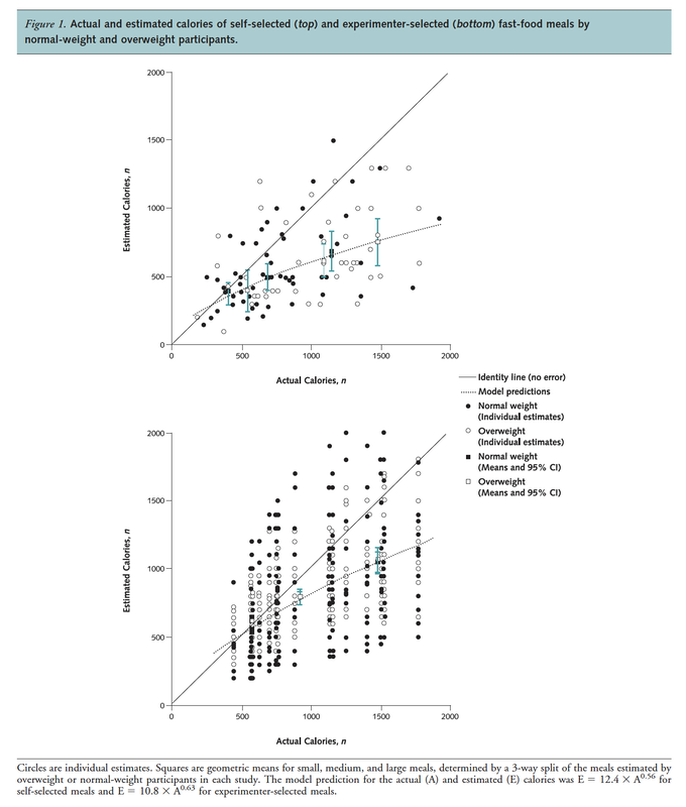

Could we better gauge how much we eat if we counted calories? Maybe not. Our experience with thousands of people suggests that most of us are terrible at estimating how many calories we have eaten so far today, or yesterday, or last week. On average, we generally think we have eaten 20% less than we actually do.[i] Those three pieces of pizza you thought were 1000 calories were actually 1200, and that 200-calorie donut was actually 240. But the real concern is with overweight people. They typically underestimate how much they eat by 40%. They think they eat about half as much as they really do. This has been a mystery. Scientists, physicians, and counselors have often blamed overweight people as trying to fool others (or themselves) about how much they are eating. Consequently, some dieticians, physicians, and family members blame and even berate overweight people as “lying” or “being in denial” as to how much they really ate. Hurtful accusations like these only make diet counseling effective at scaring overweight people off rather than changing them.[ii] Over the years we have had some overweight people in the Food and Brand Lab. Counter to what the experts say, these people always seemed to be pretty accurate at estimating the calorie content of all sorts of different foods. They were certainly no less accurate than the skinniest people in the lab. This was just the opposite of what all the classic scientific studies report. Why? To better understand this, we teamed up with a clever French researcher and good friend, Pierre Chandon. Together we discovered an important key to this mystery in research in an area called psychophysics. It seems that when estimating almost anything – such as weight, height, brightness, loudness, sweetness, and so on – we consistently underestimate things as they get larger. For instance, we will be fairly accurate at estimating the weight of a 2 lb. rock but will grossly underestimate the weight of an 80 lb. rock. We will be fairly accurate in estimating the height of a 20 foot building but will grossly underestimate the height of a 200 foot building. Chandon believes this is the key to the calorie mystery. At high levels all of us – normal weight and overweight alike – underestimate calorie levels with mathematical predictability.[iii] The secret to this mystery may not in the size of the people, but in the size of the meal.[iv] The bigger the meal, the less accurate we all are at estimating how many calories it has. To test this idea, we started in the lab and moved to a food court. First, we recruited 150 people who were either normal weight or obese. We then bought a dozen different meals of all different types – small sandwiches, huge sandwiches with chips, small chicken dinners, large chicken dinners with fries and a 32 ounce Coke, and so on. We asked each person to estimate the number of calories in each of the 12 meals. The results were alike, regardless of a person’s weight. The smaller the meal, the more accurate people are at estimating its calorie-level. The larger and larger the meal, the fewer and fewer calories they thought it contained. Everyone estimated huge 2000 calorie meals as only having 1200 calories or so. There were no differences in the estimates of the skinniest people or of the largest people. If normal weight and overweight people are equally biased in their estimates of calories, why is it that overweight people are almost always off by 40%? We ran a second study in a number of food courts to find out why. In these food courts, we asked 200 people randomly selected people what they had for lunch and how many calories they thought they ate (and drank). The more people had eaten, the less accurate they were. Someone eating a small, 300 calorie hamburger and a salad would underestimate the calories by about 10%, but someone eating a 900 calorie Monsterburger would underestimate it by a whopping 40%. It did not matter whether the person was skinny or huge, male or female, the bigger the meal, the less they thought they ate. It is “meal size,” not “people size” that determines how accurate we will be at estimating how many calories we have eaten. That popsicle-stick skinny person eating a 2000 calorie Thanksgiving dinner will underestimate how much they have eaten by just as much as the heavy person eating a 2000 calorie pizza dinner. The trouble is that the heavy person tends to eat a whole lot more of these big meals. It's meal-size, not people-size. References

[i]This gap in our calorie estimation and the exaggerated gap among obese peole has been widely reported by top scholars over the past 20 years. The classic studies include: David Lansky and Kelly D. Brownell, "Estimates of food quantity and calories: errors in self-report among obese patients," American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (1982), 35:4, 727-32. Steven W. Lichtman, Krystyna Pisarska, Ellen R. Berman, Michele Pestone, H. Dowling, E. Offenbacher, H. Weisel, S. Heshka, D.E. Matthews, S.B. Heymsfield, "Discrepancy Between Self-reported and Actual Caloric Intake and Exercise in Obese Subjects," New England Journal of Medicine (1992), 327:27, 1893-1898. M. Barbara E. Livingstone and Alison E. Black, "Markers of the Validity of Reported Energy Intake," Journal of Nutrition (2003), 133:3, 895S-920S. Janet A. Tooze, Amy F. Subar, Frances E. Thompson, Richard Troiano, Arthur Schatzkin, and Victor Kipnis, "Psychosocial Predictors of Energy Underreporting in a Large Doubly Labeled Water Study," The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2004),79:5, 795-804. [ii]Shirley S. Wang, Kelly Brownell, and Thomas Wadden, “The Influence of the Stigma of Obesity on Overweight Individuals,” International Journal of Obesity (October 2004), 28:10, 1333-1337. [iii] This is mathematically predicted by a compressive power function. The math is so painful, it even makes me weary. Anyway, the details (including the math) can be found in the very dense and very cool following article in one of the top journals in this field: Pierre Chandon and Brian Wansink, “Obesity and the Calorie Underestimation Bias: A Psychophysical Model of Fast-food Meal Size Estimation,” Journal of Marketing Research, (2006).

0 Comments

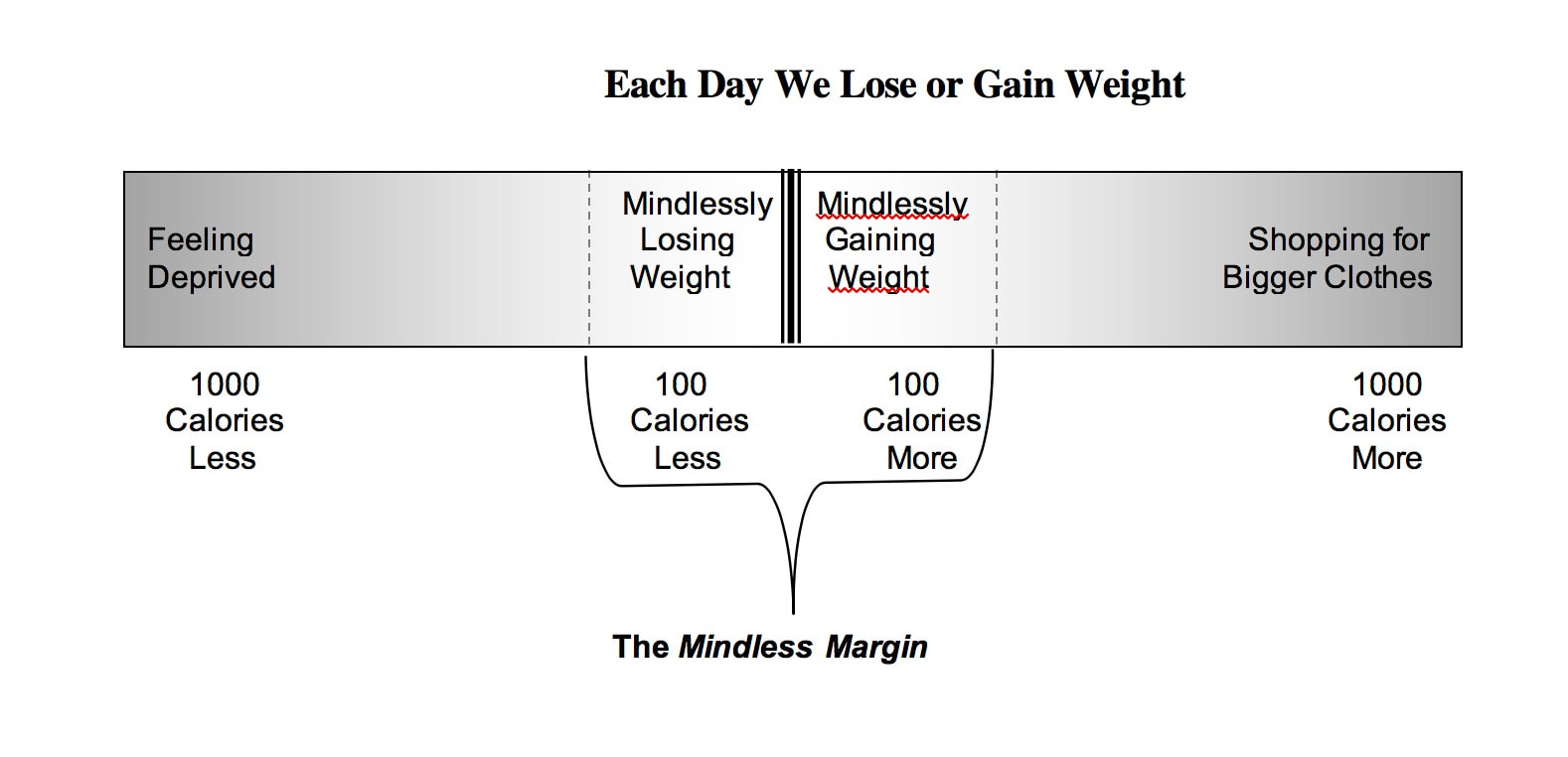

No one goes to bed skinny and wakes up fat. Most people gain (or lose) weight so gradually they cannot really figure out how it happened. They do not remember changing their eating or exercise patterns.[i] All they remember is once being able to fit into their favorite pants without having to hold their breathe and hope they can get the zipper to budge. Sure, there are exceptions. If we gorge ourselves at the all-you-can-eat pizza buffet, then clean out the chip bowl at the Superbowl party, then stop by the Baskin-Robbins drive-through for a “Belly Buster” Sundae on the way home, we realize we have gone too far over the top. But on most days we have very little idea whether we have eaten 50 calories too much or 50 calories too little. In fact, most of us would not know if we ate 200 or 300 calories more or less than the day before. This is the Mindless Margin. It is the margin or the zone in which we can either slightly overeat or slightly undereat without being aware of it. Suppose you can eat 2000 calories a day without either gaining or losing weight.[ii] If one day, however, you only ate 1000 calories, you would know it. You would feel weak, light-headed, cranky, and you would snap at the dog. On the other hand you would also know it if you ate 3000 calories. You would feel a little heavier, slower, and more like flopping on the couch and petting the cat. If we eat way too little, we know it. If we eat way too much, we know it. But there is a calorie range – a Mindless Margin– where we feel fine and are unaware of small differences. That is, the difference between 1900 calories and 2000 calories is one we cannot detect, nor can we detect the difference between 2000 and 2100 calories. But over the course of a year, this mindless margin would either cause us to lose ten pounds or to gain ten pounds. It takes 3500 extra calories to equal one pound. It does not matter if we eat these extra 3500 calories in one week or gradually over the entire year. They will all add up to one pound. This is the danger of creeping calories. Just 10 extra calories a day – 1 stick of Doublemint gum or 3 small Jelly Belly jelly beans – will make you a pound more portly one year from today.[iii] Only three Jelly Bellies a day. Fortunately, the same thing happens in the opposite direction. One colleague of mine, Stacy, had lost around 25 pounds during her first two years at a new job. When I asked how she lost the weight, she could not really answer. After some persistent questioning, it seemed that the only deliberate change she had made two years earlier was to give up caffeine. She switched from coffee to herbal tea. That did not seem to explain anything. “Oh, yeah,” she said, “And because I gave up caffeine, I also stopped drinking Coke.” She had been drinking about six cans a week – far from a serious habit – but the 139 calories in each Coke translated into 14 pounds a year. When she quit, she was not even aware of why she had lost weight. In her mind all she had done was cut out caffeine. Herein lies the secret of the Mindless Margin. This Mindless Marginis that small range where we make slight changes to our routine that we hardly notice. Nevertheless, these changes can have a gradual – but eventually big – impact on our weight. They can make the difference between being 10 pounds heavier next New Years Day or 10 pounds lighter. Cutting out our favorite foods is a bad idea. Cutting down on how muchwe eat is mindlessly doable. Many fad diets focus more on the typesof foods we can eat rather than how much we should eat. The problem is not that we order beef instead of a low-fat chicken breast. The problem is that the beef is often twice the size. A low-fat chicken breast that we resent having to eat is no better for our long-term diet than a tastier but slightly smaller piece of beef. If we are looking at only a 100 or 200 calories difference a day, these are not calories we will miss. We can trim them out of our day relatively easy – and unknowingly. The key is to do it unknowingly – mindlessly. In a classic article in Science,Drs. James O. Hill and John C. Peters showed that cutting only 100 calories a day from our diets will prevent weight gain in most of the US population.[iv]The majority of people only gain a pound or two each year, and their calculations showed that anything a person does to make this 100 calorie difference will lead most of us to loseweight. We can do it by walking an extra 2000 steps each day (about one mile), or we can do it by eating 100 calories less than we otherwise would. The best way to trim 100 or 200 calories a day is to do it in a way which does not make you feel deprived. It is so much easier to rearrange your kitchen and change a few eating habits so you do not have to think about eating less or differently. This is the silver lining to this dark, cloudy sky. The same things that lead us to mindlessly gain weight can also help us mindlessly lose weight. How much weight? Unlike the 3:00 AM infomercials, it would not be 10 pounds in 10 hours, or 10 pounds in 10 days. It is not even going to be 10 pounds in 10 weeks. You would notice that, and you would feel deprived. Instead, suppose you stay within the Mindless Margin for losing weight and trim 100-200 calories a day. You would probably not feel deprived, but in 10 months you would be in the neighborhood of 10 pounds lighter. It would not put you in this year’s Sports Illustratedswimsuit issue, but it might put you back in some of your “signal” clothes, and it will make you feel better without costing you bread, pasta, and your comfort foods. The theme of Mindless Eatingis that there are many things around us that manipulate or deceive us into eating more than we otherwise would. Popcorn buckets manipulate us, names confuse us, plates deceive us, friends unwittingly lead us astray, lighting and music fool us, colors miscue us, shapes trick us, and on and on. But all of them do so very subtly. Mindless Eating helps you generate mindlessly-easy solutions to trim excess calories out of your life in a way in which you will not miss them. Each chapter specifically illustrates what researchers know about mindless eating, and each shows how you can use the same tricks to reverse how much you eat. There are a lot of invisible traps out there that we unknowingly let trick us into overeating. What you can do is outlined in the next chapters, but we are first going to look at what causes us to decide how much we want to eat. Once we understand why we eat how much we eat, we can more clearly see how to change it. References

[i]N. E. Sherwood, Robert W. Jeffry, Simone French, et al., “Predictors of Weight Gain in the Pound of Prevention Study,” International Journal of Obesity(April 2000), 24:4, 395-403. [ii]If you burn off the same number of calories each day as you eat, you are “in energy balance.” The exact number of calories you need to be in energy balance varies depending on your weight and how much you move during the day. Smaller adults burn fewer calories a day than larger adults; active people more than inactive people. [iii]A pound is roughly equivalent to 3500 calories. Eating three Jelly Belly jelly beans a day (12 calories) would lead to are 4380 over the year. Similarly drinking one less can of Coca-Cola (139 calories) each day would amount to 101,470 calories – 29 lbs. – over a 2 year period. [iv] Details can be found in James O. Hill and John C. Peters (1998), “Environmental contributions to the obesity epidemic,” Science, 280 (5368): 1371-1374. [v]This person, Jay S. Walker, also supplemented this with lots and lots of exercise. Think 20% -- More or Less.

While most Americans stop eating is when they are full, those in leaner cultures[i]stop eating when they are no longer hungry. There is probably a big calorie gap between the point where an Okinawan says, “I’m no longer hungry” and where an American says, “I’m full.” Actually the Okinawans even have a word for it. They call the concept, “hara hachi bu” – eating until you’re just 80% full. Most of us are about as accustomed with Okinawa, as we are with eating until we are no longer hungry. We are best off dishing out all the food we think we want beforewe start to eat. • Think 20% less. Dish out 20% less of whatever you think you might want to eat. You probably won’t miss it. In most of our studies, when people eat 20% less, they never realize it. If they eat 30% less, they realize it, but 20% is still under the radar screen. • For healthy foods, think 20% more. This works great for fruits and vegetables. If we cut down how much pasta we dished out by 20%, we might want to increase the veggies by 20%. [i]Our sins of dietary excess can be compared to those of French people (French Women Don’t Get Fat), tropical people (The Tropical Diet), Mediterranean people (The Mediterranean Diet), and even Okinawans (The Okinawa Diet Plan). Suppose you make a daily change in your life, like you eat one less 250 calorie candy bar or you walk one extra mile and burn up an extra 100 calories. If you do this for every day, how much less will you weigh in a year?

If you make a change, there’s an easy way to estimate how much weight you will lose in a year. You simply divide the calories by 10. That’s the number of pounds you’ll lose if you are otherwise in energy balance. One less 270 calorie candy bar each day = 27 fewer pounds in a year One less 140 calorie soft drink each day = 14 fewer pounds in a year One less 420 calorie bagel or donut each day = 42 fewer pounds in a year The same thing works with burning calories, walking one extra daily mile is 100 calories and 10 pounds a year. Exercise is good, but some think it is a lot easier to give up a candy bar than to walk 2.7 miles to a vending machine. From Mindless Eating, p. 31 The acid test for mindless eating is wolfing down a food when we know we are not hungry. How many times have we done this? Most of us could start counting as recently as today.

Over coffee, a new friend commented that he had lost 30 pounds within the past year.[i] When I asked him how, he explained he didn’t stop eating potato chips, pizza, or ice cream. He ate anything he wanted, but if he had a craving when he was not hungry he would say – out loud – “I’m not hungry but I’m going to eat this anyway.” Having to make that declaration – out loud – would often be enough to prevent him from mindlessly indulging. Other times, he would take a nibble but be much more mindful of what he was doing. Reference [i]This person, Jay S. Walker, also supplemented this with lots and lots of exercise. You know how it is. One day you are mindlessly eating ice cream in front of an open freezer door and – bam – all of a sudden you remember you have to be at the Academy Awards ceremony in three days.

How do the movie stars lose those last minute pounds before walking the runway at the Oscars? An article in People showed that what they usually do is drastic, painful – and temporary.[i] •Emma Thompson: I try not to eat sugar, and I don’t eat bread and biscuits. Actually, to be frank, I really don’t eat any of the things I love, which is unfortunate. But I will get back to ice cream soon, which is my favorite food. •Tara Reid: I won’t eat that morning and that week I will only eat protein – egg whites and chicken. It makes a big difference. You look hot for a week, but you gain it all back the next. I also drink way more water. •Vivian A. Fox: I pop herbal laxatives and drink as much coffee as I can to flush everything out. •Melissa Rivers: I limit my calorie intake and work out like crazy. I try to eat really clean the week prior. I always substitute one meal for just a salad with dressing on the side, and I dip my fork in the dressing. •Bill Murray: I did 200,000 crunches. Drastic? Yes. Successful? As you can see from their answers, these deprivation diets worked only as long as was absolutely necessary. Five minutes after the Academy Awards ceremony is over, it is back to the normal routine, and the 10 pounds that were lost begin to find their way home again. Unless you are not yet finished with your 200,000 crunches. [i]Quotations were adopted from “Last-Minute Diet Secrets, People, March 16, 2004, pp. 122-5. We have all heard of somebody’s cousin’s sister who went on a huge diet before her high school reunion, lost tons of weight, kept it off, won the lottery, and lived happily ever after. Yet we also know about 95 times as many people who started a diet and gave up in discouragement, or who started a diet, lost weight, gained more weight, and thengave up in discouragement.[i] After that, they started a different diet and repeated the same depriving, discouraging, demoralizing process. Indeed, it is estimated that over 95% of all people who lose weight on a diet, gain it back.[ii] Most diets are deprivation diets. We deprive ourselves or deny ourselves of something – carbohydrates, fat, red meat, snacks, pizza, breakfast, chocolate, and so forth. Unfortunately, deprivation diets don’t work for three reasons: 1) Our body fights against them, 2) our brain fights against them, and 3) our day-to-day environment is booby-trapped with food. Millions of years of evolution have made our body too smart to fall for our little, “I’m-only-eating-salad,” trick. Our body’s metabolism is efficient. When it has plenty of food to burn, it turns the furnace up and burns up our fat reserves faster. When it has less food to burn, it turns down the furnace and burns it more slowly and efficiently. This efficiency helped our ancestors survive famines and barren winters. It does not help today’s deprived dieter. If you eat too little, the body goes into conservation mode and makes it even tougher to burn those pounds off. This type of weight loss is not mindless. It is like pushing a boulder up hill every second of every day. How much weight loss triggers the conservation switch? It seems that we can lose half a pound a week without triggering a metabolism slow-down.[iv]Some people may be able to lose more, but everyone can lose at least half a pound a week and still be in full-burn mode. The only problem is that this is too slow for many people. Weight loss has to be all or nothing. This is why so many impatient people try to lose it all and end up losing nothing. Now for our brains. If we consciously deny ourselves something again and again, we are likely to end up craving it more and more.[v] It does not matter whether you are deprived of affection, vacation, television, or your favorite foods. Being deprived from anything you really like is not a great way to enjoy life. Nevertheless, the first thing many dieters do is cut out their comfort foods. This becomes a recipe for dieting disaster because any diet that is based on denying yourself the foods you really like is going to be really temporary. The foods we do not bite can come back to bite us. When the diet ends – either because of frustration or because of temporary success – you are back wolfing down these comfort foods with a hungry vengeance. With all that sacrificing you’ve been doing, there is a lot of catching up to do. When it comes to losing weight, we cannot rely only on our brain, or our “cognitive control,” A.K.A. willpower.[vii] We make an estimated 248[viii]food-related decisions each day, and it is almost impossible to have them all be text-book perfect. We have millions of years of evolution and instinct telling us to eat as often as we can and to eat as much as we can. Most of us simply do not have the mental fortitude to stare at a plate of warm cookies on the table and say, “I’m not going to eat a cookie, I’m not going to eat a cookie,” and then not eat the cookie. There is only so long before our “No, no, maybe, maybe” turns into a “Yes.” Our bodies fight against deprivation, and our brains fight against deprivation.[ix]And to make matters worse, our day-to-day environment is set-up to booby-trap any half-hearted effort we can muster up.There are great smells on every fast food corner. There are warm, comfort food feelings we get from television commercials. There are better-than-homemade tasting 85 cent snacks in every vending machine and gas station. We have billions of dollars worth of marketing giving us the perfect foods that our little hearts and big tummies desire. Yet before we blame those evil marketers let us look at the traps we set for ourselves. We make an extra “family-size” portion of pasta we make so no one goes hungry. We lovingly leave latch-key snacks on the table for our children (and ourselves). We use the nice, platter-size dinner plates that we can pile up with food. We heat up a piece of apple pie in the microwave while the lonely apple shivers in the crisper. Best intentions aside, we are Public Enemy #1 when it comes to booby-trapping the diets and willpower of both ourselves and our family. The good news is that the same levers that almost invisibly lead you to slowly gain weight can also be pushed in the other direction to just as invisibly lead you to slowly lose weight. This will lead us to lose weight unknowingly. If we do not realize we are eating a little less than we need, we do not feel deprived. If we do not feel deprived, we are less likely to backslide and find ourselves overeating to compensate for everything we have forgone. The key lies in the Mindless Margin. References

[i]The speed at which you regain weight after going off a diet is almost always directly related to the speed you lost the weight to begin with. If you miraculously lose 10 pounds in 2 days with the new Celebrity Fad Diet, you are likely to miraculously gain it back almost as fast. [ii]See Maureen T. Mcguire, Rita R. Wing, Mary L. Klem and James O. Hill, “What predicts weight regain in a group of successful weight losers?” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology(1999), 67:2, 177-185. [iii]Quotations were adopted from “Last-Minute Diet Secrets, People, March 16, 2004, pp. 122-5. [iv] This conclusion from a series of studies is alluded to in David A. Levitsky, “The Non-regulation of Food Intake in Humans: Hope for Reversing the Epidemic of Obesity,” Physiology & Behavior(December 2005), 86:5, 623-632. [v]Much of the best work of restrained eaters has been conducted by Janet Polivy and C. Peter Herman. A typical example of this is Janet Polivy, J. Coleman and C. Peter Herman, “The Effect of Deprivation on Food Cravings and Eating Behavior in Restrained and Unrestrained Eaters,”International Journal of Eating Disorders(December 2005), 38:4, 301-309. [vi]This syndicated column was widely reprinted with the name of the nationally-known psychologist. This account was taken from “News of the Weird,” Funny times, October 2005, p. 25. Lisa G. Berzins, [vii]John P. Foreyt, “Need for Lifestyle Intervention: How to Begin,” American Journal of Cardiology,(August 22, 2005), 96:4A, pp. 11-14. [viii]What is interesting is that most people initially think they only make an average of less than 30 of these decisions. It’s evidence of how mindless they are. More can be found in Brian Wansink and Colin R. Payne (2006), “Estimates of Food-related Decisions Across BMI,” under review at Psychological Reports. [ix]The best current thinking on this is being done by Roy Baumeister. See Roy F. Baumeister, “Yielding to Temptation: Self-Control Failure, Impulsive Purchasing, and Consumer Behavior,” Journal of Consumer Research(2002), 28:4, 670-76. Other work in the marketing area include that by Erica M. Okada, “Justification Effects on Consumer Choice of Hedonic and Utilitarian Goods,” Journal of Marketing Research(2005), 42:1, 43-53, and by Baba Shiv and Alexander Fedorikhin, “Heart and Mind in Conflict: The Interplay of Affect and Cognition in Consumer Decision Making,” Journal of Consumer Research(December 1999), 26, 278-92. |

The Mission:For 30 years my Lab and I have focused on discovering secret answers to help people live better lives. Some of these relate to health and happiness (and often to food). Please share whatever you find useful.

Blog Categories

All

|

||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed