|

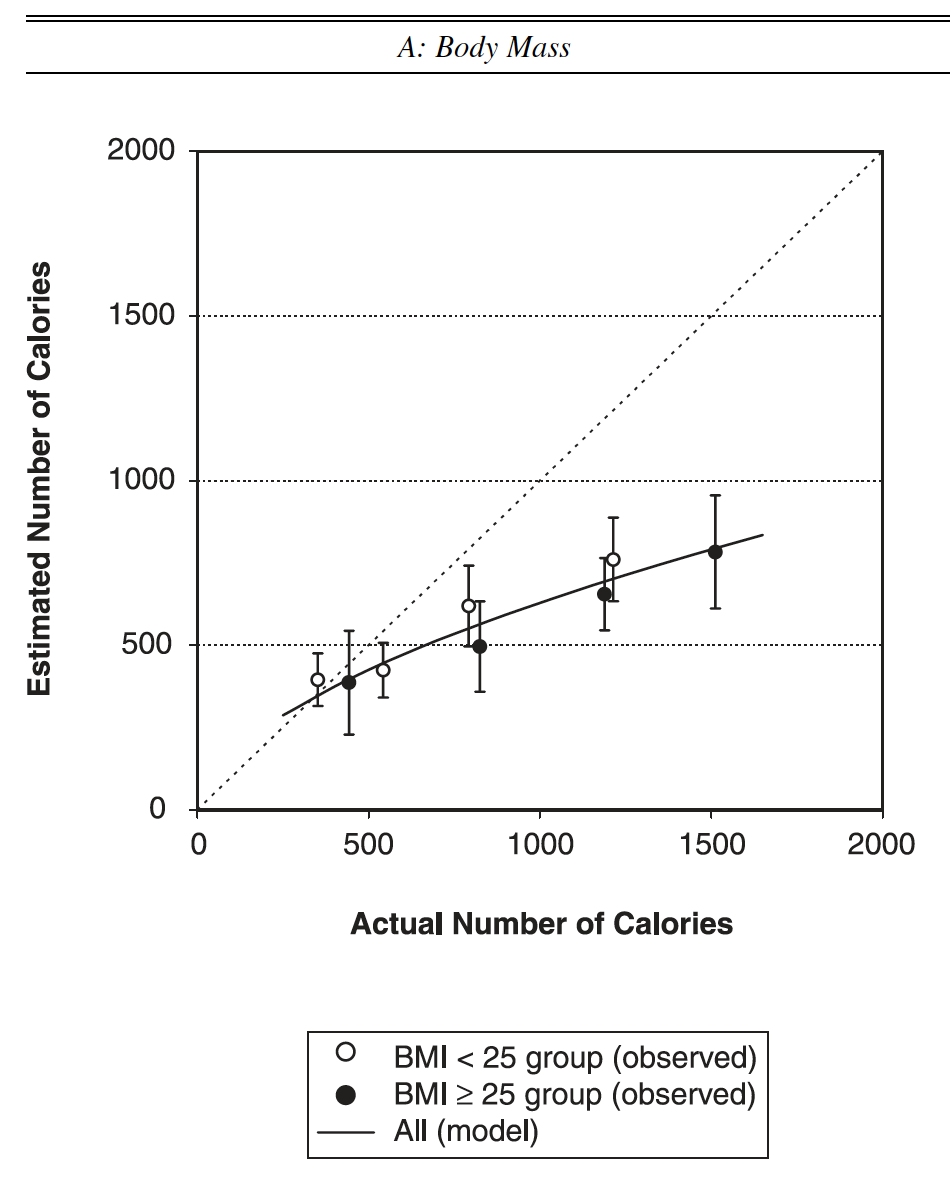

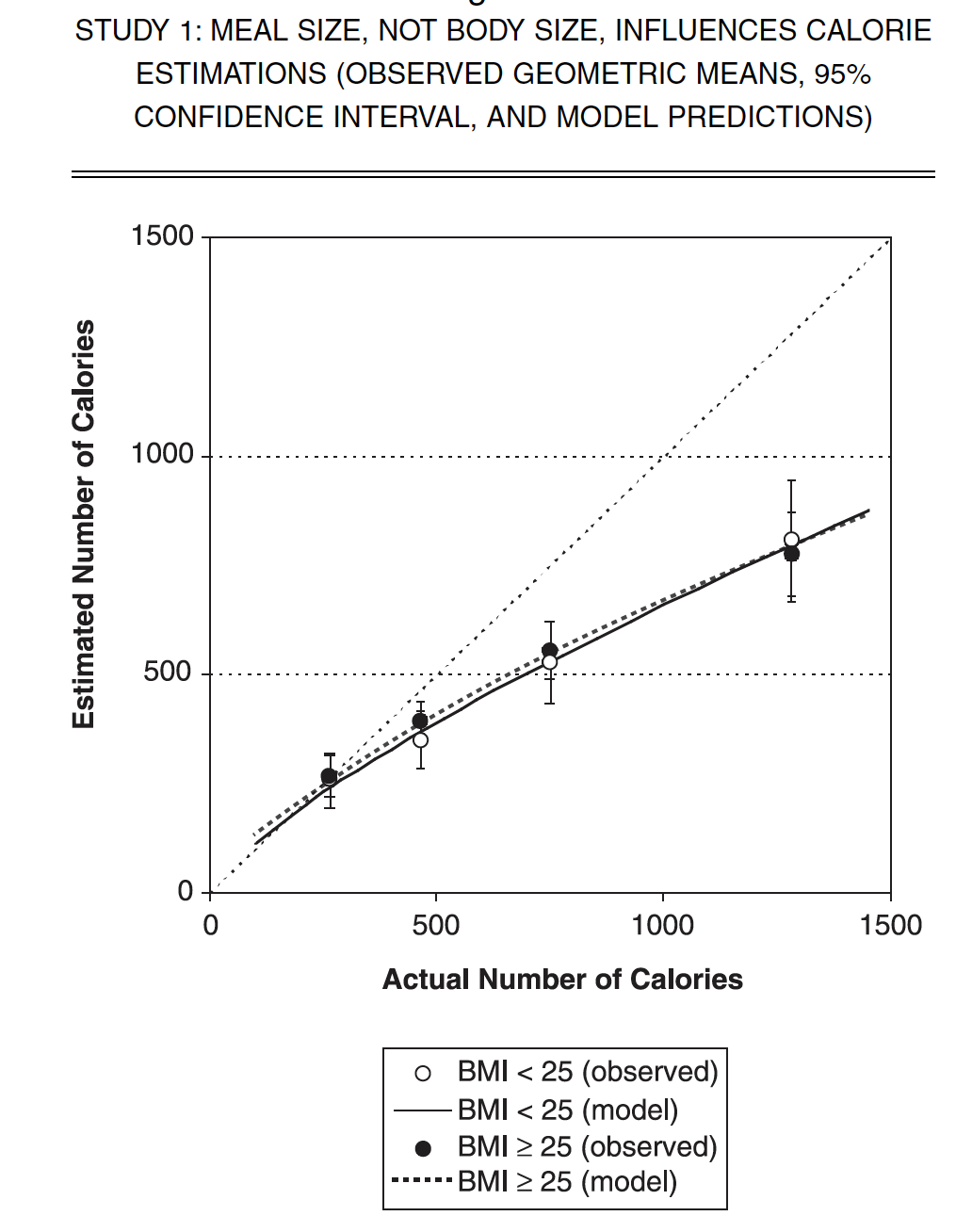

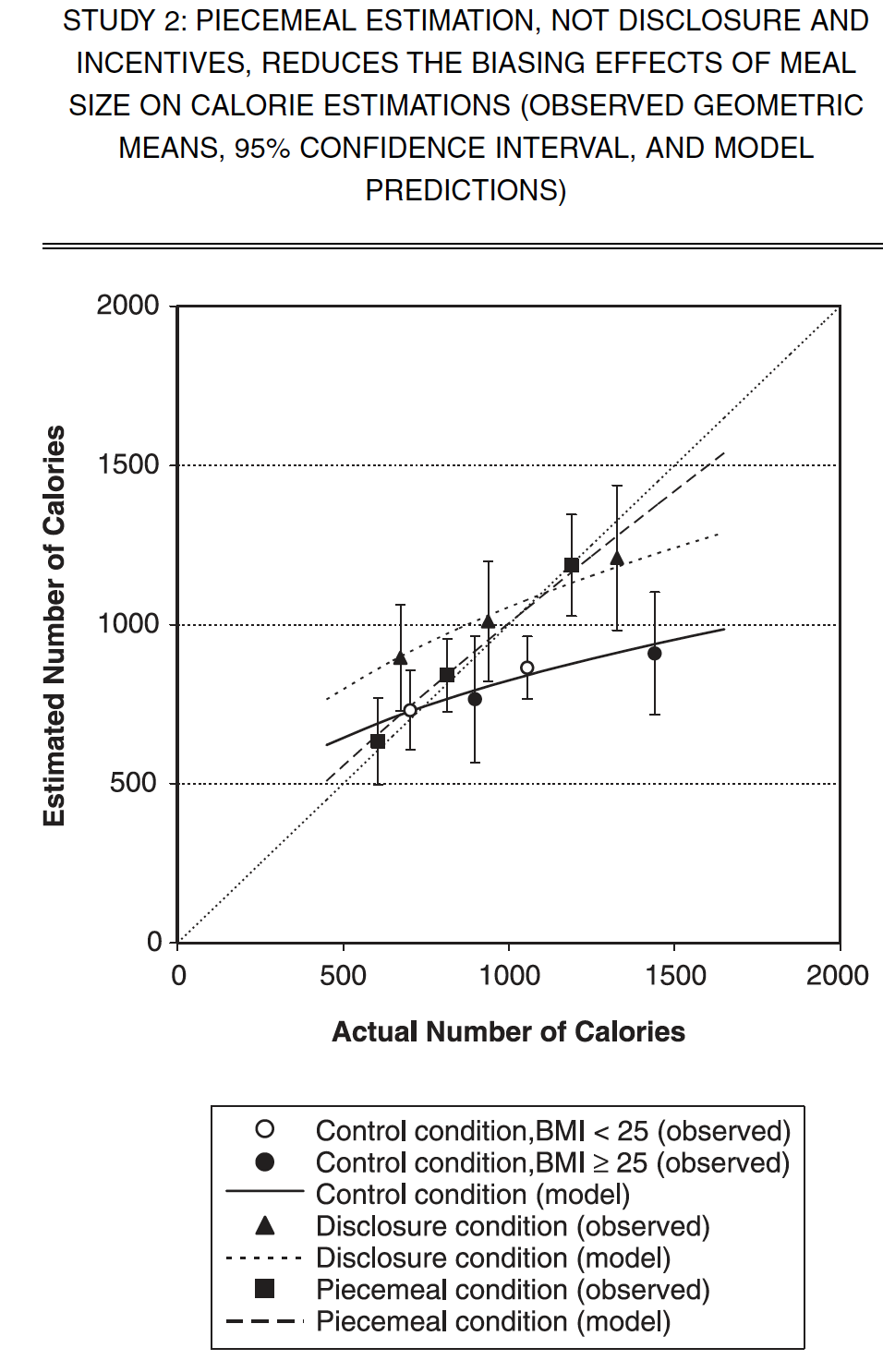

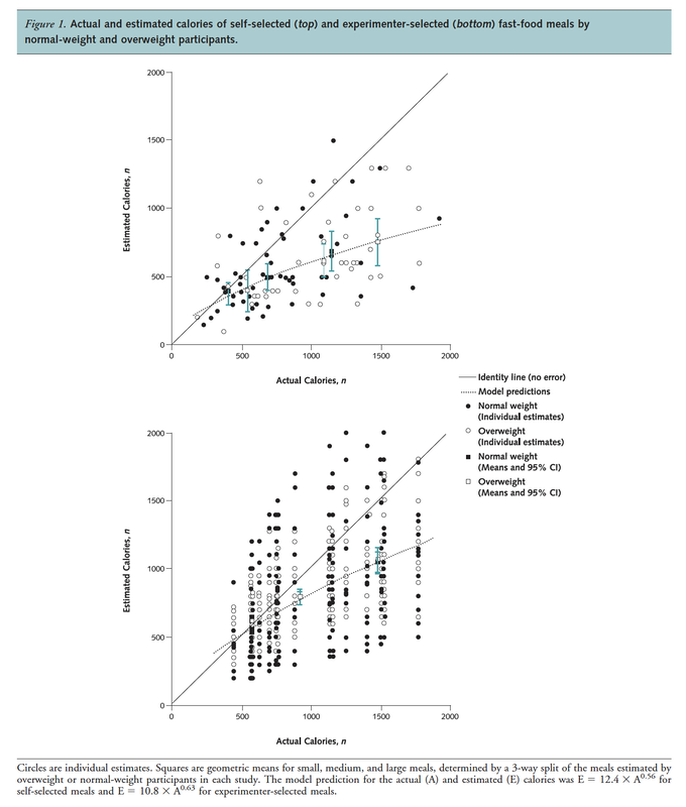

Could we better gauge how much we eat if we counted calories? Maybe not. Our experience with thousands of people suggests that most of us are terrible at estimating how many calories we have eaten so far today, or yesterday, or last week. On average, we generally think we have eaten 20% less than we actually do.[i] Those three pieces of pizza you thought were 1000 calories were actually 1200, and that 200-calorie donut was actually 240. But the real concern is with overweight people. They typically underestimate how much they eat by 40%. They think they eat about half as much as they really do. This has been a mystery. Scientists, physicians, and counselors have often blamed overweight people as trying to fool others (or themselves) about how much they are eating. Consequently, some dieticians, physicians, and family members blame and even berate overweight people as “lying” or “being in denial” as to how much they really ate. Hurtful accusations like these only make diet counseling effective at scaring overweight people off rather than changing them.[ii] Over the years we have had some overweight people in the Food and Brand Lab. Counter to what the experts say, these people always seemed to be pretty accurate at estimating the calorie content of all sorts of different foods. They were certainly no less accurate than the skinniest people in the lab. This was just the opposite of what all the classic scientific studies report. Why? To better understand this, we teamed up with a clever French researcher and good friend, Pierre Chandon. Together we discovered an important key to this mystery in research in an area called psychophysics. It seems that when estimating almost anything – such as weight, height, brightness, loudness, sweetness, and so on – we consistently underestimate things as they get larger. For instance, we will be fairly accurate at estimating the weight of a 2 lb. rock but will grossly underestimate the weight of an 80 lb. rock. We will be fairly accurate in estimating the height of a 20 foot building but will grossly underestimate the height of a 200 foot building. Chandon believes this is the key to the calorie mystery. At high levels all of us – normal weight and overweight alike – underestimate calorie levels with mathematical predictability.[iii] The secret to this mystery may not in the size of the people, but in the size of the meal.[iv] The bigger the meal, the less accurate we all are at estimating how many calories it has. To test this idea, we started in the lab and moved to a food court. First, we recruited 150 people who were either normal weight or obese. We then bought a dozen different meals of all different types – small sandwiches, huge sandwiches with chips, small chicken dinners, large chicken dinners with fries and a 32 ounce Coke, and so on. We asked each person to estimate the number of calories in each of the 12 meals. The results were alike, regardless of a person’s weight. The smaller the meal, the more accurate people are at estimating its calorie-level. The larger and larger the meal, the fewer and fewer calories they thought it contained. Everyone estimated huge 2000 calorie meals as only having 1200 calories or so. There were no differences in the estimates of the skinniest people or of the largest people. If normal weight and overweight people are equally biased in their estimates of calories, why is it that overweight people are almost always off by 40%? We ran a second study in a number of food courts to find out why. In these food courts, we asked 200 people randomly selected people what they had for lunch and how many calories they thought they ate (and drank). The more people had eaten, the less accurate they were. Someone eating a small, 300 calorie hamburger and a salad would underestimate the calories by about 10%, but someone eating a 900 calorie Monsterburger would underestimate it by a whopping 40%. It did not matter whether the person was skinny or huge, male or female, the bigger the meal, the less they thought they ate. It is “meal size,” not “people size” that determines how accurate we will be at estimating how many calories we have eaten. That popsicle-stick skinny person eating a 2000 calorie Thanksgiving dinner will underestimate how much they have eaten by just as much as the heavy person eating a 2000 calorie pizza dinner. The trouble is that the heavy person tends to eat a whole lot more of these big meals. It's meal-size, not people-size. References

[i]This gap in our calorie estimation and the exaggerated gap among obese peole has been widely reported by top scholars over the past 20 years. The classic studies include: David Lansky and Kelly D. Brownell, "Estimates of food quantity and calories: errors in self-report among obese patients," American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (1982), 35:4, 727-32. Steven W. Lichtman, Krystyna Pisarska, Ellen R. Berman, Michele Pestone, H. Dowling, E. Offenbacher, H. Weisel, S. Heshka, D.E. Matthews, S.B. Heymsfield, "Discrepancy Between Self-reported and Actual Caloric Intake and Exercise in Obese Subjects," New England Journal of Medicine (1992), 327:27, 1893-1898. M. Barbara E. Livingstone and Alison E. Black, "Markers of the Validity of Reported Energy Intake," Journal of Nutrition (2003), 133:3, 895S-920S. Janet A. Tooze, Amy F. Subar, Frances E. Thompson, Richard Troiano, Arthur Schatzkin, and Victor Kipnis, "Psychosocial Predictors of Energy Underreporting in a Large Doubly Labeled Water Study," The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2004),79:5, 795-804. [ii]Shirley S. Wang, Kelly Brownell, and Thomas Wadden, “The Influence of the Stigma of Obesity on Overweight Individuals,” International Journal of Obesity (October 2004), 28:10, 1333-1337. [iii] This is mathematically predicted by a compressive power function. The math is so painful, it even makes me weary. Anyway, the details (including the math) can be found in the very dense and very cool following article in one of the top journals in this field: Pierre Chandon and Brian Wansink, “Obesity and the Calorie Underestimation Bias: A Psychophysical Model of Fast-food Meal Size Estimation,” Journal of Marketing Research, (2006).

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Mission:For 30 years my Lab and I have focused on discovering secret answers to help people live better lives. Some of these relate to health and happiness (and often to food). Please share whatever you find useful.

Blog Categories

All

|

||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed