If you’re a PhD student, you are in great company. But "being in great company" has a very special meaning that's important not to overlook -- it means you are not alone. Your bumpy PhD experience is surprisingly universal across different schools and different programs. If you’re a PhD student in microbiology, you have more in common with a PhD student in history than someone in medical school. If you’re a PhD student in economics, you have more in common with a PhD student in physics than with an MBA student. Despite this universal experience, many, many PhD students feel very alone. They feel anxious about their uncertain future, anxious about their abilities, and anxious about a personal life that seems to be passing them by. Having been an informal confident to many PhD students in different majors or with different advisors, I’ve found that many of their real concerns are difficult for them to talk about. This further magnifies their feeling of isolation because they don’t realize how many other people have faced and often conquered a similar problem. There’s power in knowing someone else found a path out of the same woods you feel you’re in. For about 20 years I taught an interdisciplinary PhD course at the University of Illinois and then at Cornell. Aside from the academic objectives, one of my personal objectives of this course was to help students begin to conquer these anxieties. One way we tried to tackle this was by asking students if they wanted to volunteer to write a short description about a “friend” who was facing a troubling problem. Many weeks we would discuss one of these anonymously written “case studies” for 10-15 minutes during class.

Two good things happened almost every week. First, the 8-16 students in the class all realized that they weren’t alone in some of the problems they faced. Second, they heard a wide range of rational (non-emotional) solutions and perspectives to each problem they probably wouldn’t have heard from an officemate or a partner.

There are three examples of PhD Student Case Studies in the downloadable pdf, and they can be used in a number of different ways.

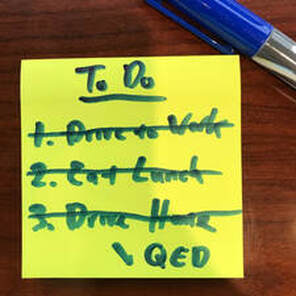

There’s power in knowing there are a lot of different ways a PhD student can get out of the woods.  There are 100 things on your mental To-Do list. There are daily duties (like email and office time) and pre-scheduled stuff (like classes and committee meetings). But what still remains at the end of the day are the things that are easy to put off because they don’t have hard or immediate deadlines – things like writing an intro to a paper, submitting an IRB proposal, drafting a grant, completing some analysis tables, and so on. At the end of the year, having finished all of these might be what makes the difference between an exceptional year and another “OK” one. But these projects are also the easiest things to put off or to only push ahead 1 inch each week. If you push 100 projects ahead 1 inch each week, you’ve made 100 inches of progress at the end of the week, but your desk is still full and you’re feeling frustratingly resigned to always be behind. This is an incremental approach. A different approach would be to push a 50-inch project ahead until it is finished and falls off the desk; then you could push a 40-inch project ahead until it falls off; and then you can spend the last of your time and energy pushing a small 10-inch project off your desk. This is the “push-it-off-the-desk” approach. Both approaches take 100-inches of work. However, the “push-it-off-the-desk” approach changes how you think and feel. You still have 97 things left to do, but you can see you made tangible progress. For about 12 years, I tried a number of different systems to do this – to finish up what was most important for the week. Each of them eventually ended up being too complicated or too constraining for me to stick with. Eventually I stopped looking for a magic system. Instead, at the end of every week, I simply listed the projects or project pieces I was most grateful to have totally finished. Super simple. It kept me focused on finishing things, and it gave me a specific direction for next week (the next things to finish). It’s since evolved into something I call a “3-3-3 Weekly Recap.” Here’s how a 3-3-3 Weekly Recap works. Every Friday I write down the 3 biggest things I finished that week (“Done”), the 3 things I want to finish next week (“Doing”), and 3 things I’m waiting for (“Waiting for”). This ends up being a record of what I did that week, a plan for what to focus on next week, and a reminder of what I need to follow up on. It helps keep me accountable to myself, and it keeps me focused on finishing 3 big things instead of 100 little things. Here’s an example of one that’s been scribbled in a notebook at the end of last week: Even though you’d be writing this just for yourself, it might improve your game. It focuses you for the week, it gives you a plan for next week, and it prompts you to follow-up on things you kind of forgot you were waiting for.

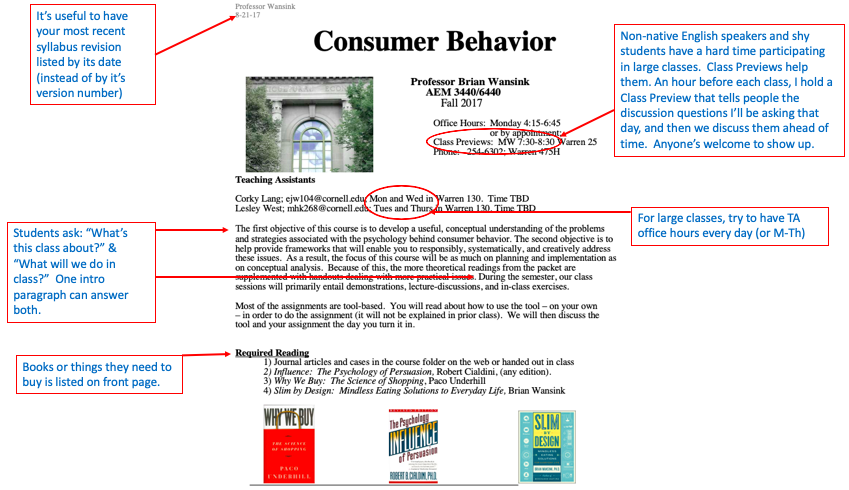

Sometimes I do it in a notebook and sometimes I type it and send it to myself as an email. It doesn’t matter the form it’s in or if you ever look back at it (I don’t), it still works. I’ve shared this with people in academia, business, and government. Although it works for most people who try it, it works best for academics who manage their own time and for managers who are supervising others. They say it helps to keep the focus on moving forward instead of either simply drifting through the details of the day or being thrown off course by a new gust of wind. If you work with PhD students or Postdocs, it could help them develop a “Finish it up” mentality, instead of a “Polish this for 3 years until it's perfect” mentality. It’s also useful as a starting point for 1-on-1 weekly meetings. If they get in the habit of emailing their 3-3-3 Recap to you each Friday, you can share any feedback and perhaps help speed up whatever it is they are waiting for. Especially if it’s something on your desk. Ouch. Good luck in pushing 3 To-Dos off your desk and getting things done. I hope you find this helps. In 2017-19, about 18 of my research articles were retracted. These retractions offer some useful lessons to scholars, and they also offer some useful next steps to those who want to publish in the social sciences. Two of these steps include 1) Choose a publishable topic, and 2) have a rough mental roadmap of what the finished paper might look. That is, what’s the positioning, the study, and the possible contribution. The topics I’ve described here offer one set of roadmaps that could be useful. First, they were of interest to journals in medicine, behavioral economics, marketing, nutrition, psychology, health, and consumer behavior. Second, they each show what a finished paper might look like. They show the positioning, relevant background research, methodological tips, and key implications.

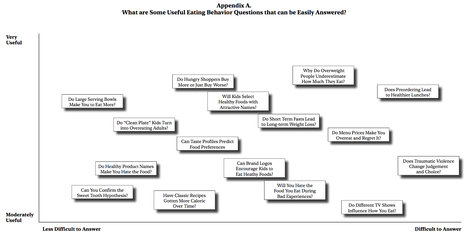

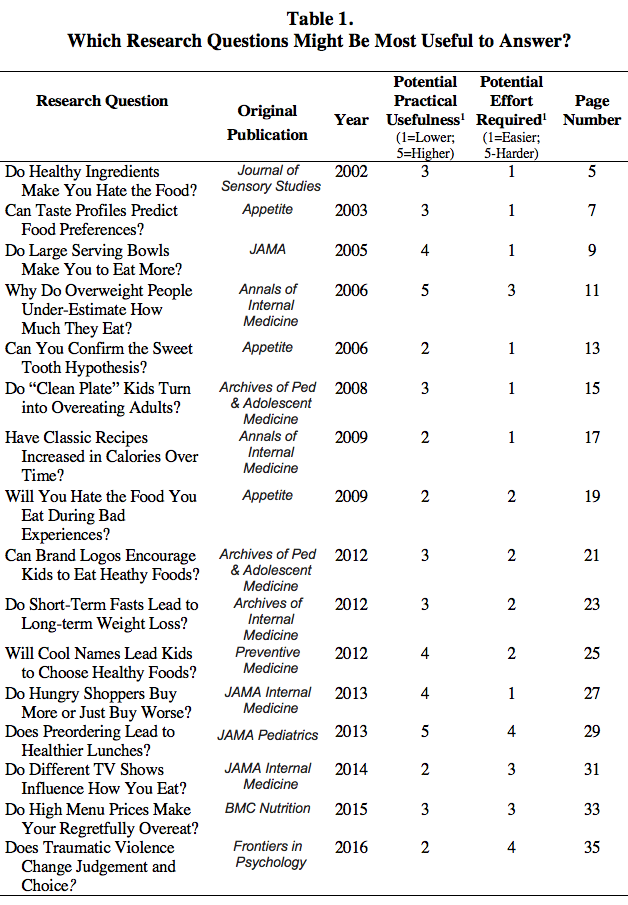

Table 1 and Appendix A lay out an estimate of how much effort it might take to do studies on these topics, and I’ve also estimated what I think the practical impact each research project might have. These are my own subjective estimates, but you might find them a useful starting point if you’re looking for a tie-breaker between two different topics. I would strongly encourage anyone who’s interested in publishing in these areas to closely follow principles of open science, from preregistration of hypotheses and analytic strategies to open materials and open data. Making specific hypotheses and testing them by following open science principles will be the best next way forward. A good introduction to these principles, along with hands-on advice, is this: Klein, O., Hardwicke, T. E., Aust, F., Breuer, J., Danielsson, H., Hofelich Mohr, A., … Frank, M. C. (2018). A practical guide for transparency in psychological science. Collabra: Psychology, 4(1), 20. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.158 Academia can be a tremendously rewarding career both you and for the people who benefit from you research. Best wishes in moving topics like these forward, and best wishes on a great career.  Some scholars are truly amazing and heroic. They’re self-made, and their career’s been flawlessly filled with perfect decisions and perfect timing. Then there’s the rest of us. The rest of us have succeeded because we were all raised, socialized, and helped by other people. Outside of academia, some of these people are obvious: parents, close relatives, coaches, and some teachers. But inside academia, not all of these people are as obvious. They might be that undergraduate professor who recommended we go to one grad school versus another, or the one who helped get us our first tenure-track job, helped lend a hand during a difficult time, or saved us from a desert island that one time by paddling through shark infested waters using only their right arm. With Thanksgiving coming up, it can be a nice chance to hit pause and think of 2-3 nonobvious people who might have done a small thing that made a big difference in your life. Doing something as simple as this can do your soul good. On one extreme, it reminds us that we aren’t the self-centered Master of our Universe as we might think when things are going great. On the other extreme, it reminds us that there are a lot of people silently cheering for us when we might think things aren’t going so great. What do you suppose would happen if you tracked these people down and game them a call? It’s four steps: 1. Find their phone number and dial. 2. “Hey, I’m ___; remember me? How are you?” 3. “It’s Thanksgiving. I was thinking of you” or "It's not Thanksgiving, but I've been thinking of you." 4. “Thanks” For about the past 30 years, I’ve tried to do this each Thanksgiving. It used to be the same 3-4 people (advisors and a post-college mentor), then a couple more, and this year I’m adding a new one. For some reason, I always look for an excuse why I shouldn’t make these calls. I always find myself pacing around before I make the first call. Part of me thinks I might be bore them, or they already know it, or it’s interrupting them, or that it’s too corny. Yet even if I have to leave voice messages, I’m always end up smiling when I get off the phone. I feel more thankful and centered. I feel happier. Maybe they feel differently too. Still, there’s some years I never made any calls, because I had good excuses. Maybe it was too late in the day, or they were probably with their family, or I called them last year, or I didn’t really have enough time to talk. I’m sure they had some good excuses – way back when – as to why they didn’t have time for me. I’m thankful they didn’t use them. If you can think of 2-3 people you’re thankful for who might not know it, you don’t have to wait until Thanksgiving next year to tell them. They won’t care that you’re a little bit late or a whole lot early. It’s only 4 steps. |

Welcome...Fun, useful, or wacky experiences about getting tenure, teaching better, publishing more, and having an incredibly rewarding career.

Categories

All

Some Blog ShortcutsArchives

September 2020

|

||||||||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed