|

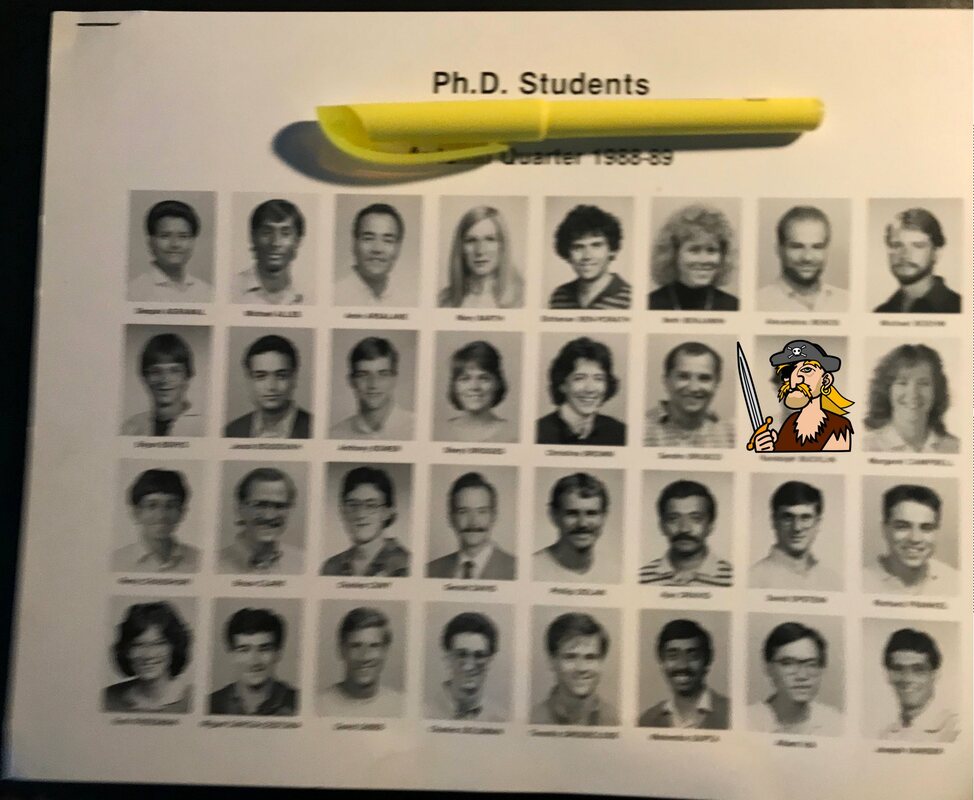

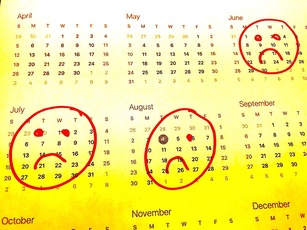

Today’s the 30th anniversary of the day when the University Registrar weighed five copies of my signed dissertation, stamped it with a red smiley face, and said, “Congratulations, Dr. Wansink.” Within 20 minutes I was shifting my Mercury Lynx into 5th gear on the 3000 mile, unairconditioned, cross-country drive to start teaching the next Tuesday. All I needed was a t-shirt that said “Yesterday I couldn’t even spell ‘Perfessor,’ and today I are one.” I annually celebrate this signature day with good steak, good wine, and having good friends over for a dinner party. I also celebrate it by writing down the best lessons I learned over the past year. Usually, they're the lessons I learned the hard way. Over 30 years, I’ve written down a ton of annual lessons in 30 different notebooks. Some is advice people gave me, and some is based on my own experience – things that are useful to me and might be useful to students and friends. Maybe it will give them a boost or save them some pain. In the spirit of counting to 30 today, here’s a sample of some of these that might be a boost or save a stumble Advice to Graduate Students 1. “The ‘P’ in PhD stands for Perseverance.” – The smartest and most talented people in PhD programs aren’t always the ones who graduate. 2. “It’s an N-period game.” When I had to find a new advisor and defend a new dissertation proposal with four months notice, the game theory economist who gave me this advice was implying that there are a lot of second and third chances in academia as long as you keep swinging. Related to this . . . 3. “Choose your best friend as your advisor.” I heard this from a Med School professor friend who then said “And choose your older brother to be your second committee member, and choose your favorite uncle to be your third.” We tend to choose our dissertation committee based on who’s most famous. Consider which professors most want you to graduate. [Read more] 4. Be a Visiting Professor. Suppose you don’t get a good offer when you graduate from your PhD program (or you get turned down for tenure). If you “settle” for a tenure-track at a school you’re not crazy about, you’ll be perceptually anchored to that type of school by both you and by others. Being a 1- or 2-year visiting professor keeps you from getting anchored, gives you more time to strengthen your vita, and lets you swing again. Career Observations 5. Do solution-focused research. Developing theory is prestigious, but coming up with a solution to an everyday problem is super gratifying. (Again, this is totally my personal preference and advice to myself.) [Read more] 6. Go to a different conference outside your field every year. Even if it’s an on-campus mini-conference in anthropology, you’ll learn a lot and it will keep you humble. 7. Leave town for your sabbatical. Moving is a hassle and there are 100 great reasons why you should spend your sabbatical at home (your spouse’s job, your kids, your doggy, your home, and so on). But I’ve never know anyone who went away for their sabbatical and who didn’t claim it was a career highlight. I’ve also never known anyone who spent their sabbatical at home and remembered anything about it two years later. 8. Writing a book is useful. Almost all academic authors are disappointed their books aren't cited more or sell more. Still, writing a book is worth it because it motivates you to organize, distill, and share what you understand about your topic, and then clarify the gaps you might want to fill in next. 9. A Leave-of-Absence is Transforming. Again, this is about moving away and clearing your head. Leaving town to take a 1- or 2-year paid leave of absence is incredibly revitalizing to every single person I've known. It either gives you amazing confidence that you can also be hugely succeed at something else, or it gives you amazing appreciation for academia. Maybe both. 10. Being fired is a temporary setback. Whether you don’t get tenure or whether something else in your career goes haywire, they say life is 10% what happens to you and 90% how you respond. If things are looking too dark, contact me and I’ll help you, or I'll find you some help. 11. Never retire. One of the great beauties of academia is you can always keep doing the parts of it you love most -- even if you don't go into work. (Here are some ideas on doing it without having later regrets.) Research Experiences 12. 90% of reviewers are great coaches. Reviewers have either made my papers better or they‘ve made me a better researcher. If it wasn’t for reviewers, some of my papers would have never been read by anyone other than me. 13. Create a Best Practices Guide for writing journal articles. – Find 30-40 favorite papers written by other researchers and list out the different strategies, tactics, and words you see them use (perhaps unconsciously) in their abstract, their opening-line, their first paragraph, their introduction, their background, theory section, tables, and so forth. When you’re finished distilling this, you’ll have a Best Practices guide that’s personalized to what you like in a paper and will be your writing guide. When I did this, my acceptance rate almost tripled. Also, papers became a lot easier and more fun for me to write. 14. Use a 2-2-2 strategy to unclog your pipeline. If a manuscript gets desk-rejected, I try to send it to the next journal within 2 days. If it gets conditionally accepted, I revise it and send it back within 2 weeks. If it gets a revise-and-resubmit that doesn’t require any additional studies, I send it back within 2 months. 15. Field studies are worth the hassle. They’re messy, hard to coordinate, inefficient, error-riddled, and harder to publish than lab studies. Still, they are usually memorable and impactful. 16. “Ideas are cheap. Execution is what pays.” Even a mediocre brainstorming session will generate 3-4 publishable ideas, and almost none will be followed up on. Edison said something like “Publishing in the Journal of [insert favorite journal here] is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration.” Executing is what matters. Productivity Tips 17. “You can either read a lot or you can write a lot, but you can't do both.” 18. "Write the first two hours of every day." The guy who told me this, pretty much said it like a command: no email, no breakfast, no class stuff. Before breakfast and before the kids wake up. It sets a productivity vibe for the whole day. [Read more] 19. Write down the 3 specific things you'll finish each day. Better to have three things completed than 20 things pushed ahead an inch. [Read more] Teaching Insights 20. "Imagine your brother, daughter, or younger self in the front row of your class." This will lead you to give your class sessions more context and more “So what?” It’s also help you cut loose a bit and give the class more punch, fun, and humor. 21. "Teach for where a student will be in 10 years." The guy who told me this is a legend. The idea is to try to get students to visualize their most successful self in 10 years. If we can teach them as the "ten-years-from-now" person they'll be, we’ll be teaching them something they couldn’t just learn from an online class. 22. Education is a buffet; be something unique. Some courses are meaty and some are refreshing; some professors are fiery and others are more chill. You don't need to be like everyone else. By being your best, genuine, earnest self, you’ll be adding variety to their educational buffet. 23. Hold class previews for participation classes. Non-native English speakers and shy students have a hard time participating in class, but class previews can help them. An hour before each class, I hold a class preview and we briefly discuss the day's discussion questions ahead of time. Anyone’s welcome to show up. [Read more] 24. Ask good students who the “must-take” teachers are. See if you can sit in on a couple of their class sessions (most are flattered and only 2 ever turned me down). Take notes about the good teaching ideas you can use. 25. “Don’t become a parody of yourself.” Good teachers slowly start to exaggerate the things they’re good at, and they eventually take it over the top and become a parody of themselves. Dramatic teachers will overfocus on drama. Entertaining teachers will overfocus on entertainment. Cool professors teachers will overfocus on coolness, and so on. [Read more] Fun, People, and Things 26. “Fun people accidently say stupid things. Don’t beat yourself up.” Some academics over-edit everything they say before they speak. If you have a more spontaneous personality, you won't be happy if you have to over edit everything you do. Small accidents will happen (but we get used to it). 27. Dress-up and show-up early for Meetings. This is one way to show respect for the profession and for my colleagues. (Again, this is totally my advice to myself.) Like a US Marine Colonel once told me, "Early is on time. On time is late." 28. Don’t apologize for who I am or hide from it. I’ve had senior colleagues give me well-meaning advice that I should never mention to anyone that I shop at Walmart, play sax in a rock band, go to church, host board game nights, do stand-up comedy, or go thrifting. What you love doing isn’t worth being self-conscious over. If those things are that big of a deal at your school, you’d probably be happier at a different school anyway. [Read more] 29. The more 1-on-1 fun stuff I do with different colleagues outside of work, the more I love my job. The crazier the stuff we do, the more we both seem to love it and remember it. 30. “Max out your TIAA-CREF retirement contribution. Then add more.” The guy who told me this was a retired English professor -- who had two very nice homes. It’s not flashy or cool to save money instead of spending it, but no one over 50 regrets having done so. *** Having an academic mind is a Blurse. It's both a blessing and a curse. It's a blessing because we are almost always looking for better ways to learn or to improve. It's a curse because we're not always very open to what others have found. We feel we have to do it ourselves, or discover it ourselves. If we hear advice from someone else, we might think it doesn't apply or that we're the exception. Ten of the lessons I mentioned are advice someone gave to me. The main reason their advice stuck with me was because I had just finished really screwing up doing it My Way: • #3 only registered when I was told I was being kicked out of the PhD program • #17-18 were only great ideas after I was fired for not publishing enough • #20-21 were brilliant the day I got the second lowest teaching ratings in the school • #26 resonated only after I'd been hissed at in class after making an unfunny comment Hopefully these might give you a boost, save you a stumble, or lead to your own self-discovered list. Being a scholar and an academic is an unbelievably great calling. Good luck having many, many great years -- each more amazing than the one before. Let me know how I can help.  "School’s starting, and I didn't get anything done this summer.” I’ve heard this every August, and I’ve said this every August. Whenever I’ve asked professors and PhD students what percent of their planned work they got accomplished over the summer, no one has ever said “All of it.” Almost everyone says something between 25 to 35%. Everyone from the biggest, most productive super stars with the biggest lab to the most motivated, fire-in-their-belly PhD student with the biggest anxiety. We are horrible estimators of how productive we’ll be over the summer. I was in academia for 35 years (including MA and PhD years), yet every single summer I never finished more than 30% of what I planned. How can we be so poorly calibrated? We never learn. We never readjust our estimate for the next summer. Next summer we’ll still only finish 25-35% of what we planned to do. There are only two weeks in the year when I’m predictably down or blue. It’s the last two weeks of August. It’s not the heat (I mostly stay indoors). It’s not the impending classes (I love teaching). It’s not all the beginning of semester meetings (I loved my colleagues and loved passing notes to them under the table). Ten years ago, I realized that I felt down the end of every August because I had to admit “school’s starting and I haven’t gotten jack done all summer.” The beginning of school is the psychological end of the Academic Fiscal Year. One solution to our August blues lies in understanding what times of the year we do like most, and to see if we can rechannel those warm-glowy feelings to August. If you had to guess the #1 favorite time of the year for most academics, you’d probably guess “The end of school.” The #2 favorite time of the year you might guess would be the “Winter or Christmas break.” What would you guess the third favorite time of the year is? Surprisingly, I’ve heard people say it’s when they turn in their Annual Activity Report (AAR). That’s the summary document they turn into their hard-to-please Department Chair that summarizes what they’ve accomplished in the prior 12 months: What they published, who they advised, what new things they’ve started, what new teaching materials they’ve created, and so forth. Snore. How could writing an Annual Activity Report be a highlight? Because it shows in black-and-white that we didn’t sleep-walk through the year. It reminds us that the publication that we now take for granted was one that we were still biting our nails about last year at this time. It reminds us of our advises who were stressing over their undergraduate thesis a year ago and who have now happily graduated. It reminds us of the cool ideas we've into hopeful projects -- ideas we hadn't even thought of a year ago.. Going back in a 12-month-ago time machine shows us what we did accomplish. It turns our focus toward what we did – and away from what we didn’t. Once we cross things off of our academic To-do list, we tend to forget we accomplished them. August might be a good time to do a mid-year AAR. It might not turn our August blues into a happy face yellow, but might at least turn it to green. A green light for a great new school year. Have a tremendous school year.  On a late afternoon about 20 years ago, I stepped into a slow elevator with my college’s most productive, famous, and taciturn senior professor. After 10 seconds of silence, I asked, “Did you publish anything yet today?” He stared at me for about 4 seconds and said, “The day’s not over.” Cool . . . very Clint Eastwood-like. Most of us have some super-productive days and we have some bad days, but most lie in-between. If we could figure out what leads to great days, we might be able to trigger more of them in our life. For instance, if you want to write a whole lot, there might be a way to set up your day so that this happens with a surprising amount of ease. Think of the most recent “great day” you had. What made it great, and how did it start? For about 20 years, every time somebody told me they had a great day, I’d ask “What made it great? How did it start out? About 50% of the time its greatness had to do with an external “good news” event like something great happening at work, great news from their kids or spouse, a nice surprise, or nice call or email from a grateful person or an old friend. The other 50% of the time, the reason for “greatness” was more “internal.” They had a super productive day, they finished a project or a bunch of errands, or they had a breakthrough solution to a problem or something they should do. External successes are easy to celebrate with our friends. Internal successes are more unpredictable. What made today a great day and what sabotaged yesterday? When people had great days, one reoccurring feature was that they started off great. There was no delay between when they got out of bed and when they Unleashed the Greatness. People said things like, “I just got started and seemed to get everything done,” or “I finished up this one thing and then just kept going.” One of the most productive authors I've known said that got up six days a week at 6:30 and wrote from 7:00 to 9:00 without interruption. Then he kissed his wife good-bye and drove into school and worked there. When I asked how long he had done that he said, “Forever.” About a year ago, I started toying with the idea that "Your first two hours set the tone for the whole day." Think of your last mediocre day. Did it start out mediocre? That would also be consistent with this notion. We can’t trigger every day to be great, but maybe we have more control than we think. If we focus on making our first two hours great, it might set the tone for the rest of the day. What we need to decide is what we can we do in those first two hours after waking that would trigger an amazing day and what would sabotage it and make it mediocre. For me, it seems writing, exercise, prayer, or meditation are the good triggers, and it seems answering emails, reading the news, or surfing are the saboteurs. Here’s to you having lots of amazing days. One’s where you can channel your best Clint Eastwood impression and say, “The day’s not over.” (This is an edited version of the "Shirking or Working from Home" blog I wrote as the Executive Director of Research for VitalSmarts).  Working from home is one of the 5,000 great benefits of being an academic. But it can also turn into too much of a good thing. Before the coronavirus, a lot of schools were hesitant to let staff work from home. “Working from home” rhymes too closely with “Shirking from home.” It includes surfing, posting, grazing, running errands, crushing Candy Crush, calling your brother “just because,” rereading online stories about the coronavirus, updating your vita, and spacing out on conference calls. But what if working from home looked different? What if working from home made you 13% more productive, made you feel more satisfied with your job, and made you half as likely to send your vita off to another school? This is in line with what was found in a 2015 Stanford study of a large Chinese travel firm called CTrip. Researchers randomly split 249 call center employees from Shanghai into two groups. For nine months, half of them kept working at their desks as usual, and the other half were told to work from home four days a week (one day a week they came into the office). Then the researchers measured everything from the number of calls they made, to job satisfaction, to breaks taken, to sick days… everything but Facebook Likes and Candy Crush scores. One conclusion: Working from home can make people more productive. But wait. Before you move all of your books back home, there’s a huge caveat from this study (aside from country, culture, and industry): These workers had very specific measures of productivity—phone calls per minute and the amount of time spent on the phone. Since working at home requires a discipline muscle that many of us need to strengthen, it’s easy to let our first days or weeks at home be structured by meetings and not our mission. That is, we might view the phone or web meetings on our calendar as the “Big rocks” of our day instead of seeing our biggest projects as our biggest rocks. After you conduct a weekly review of the projects that are most pressing, these suggestions might help. • Identify the three biggest project tasks you need to complete each day (not including meetings). • Make a promise to complete these tasks and deliver results to another person (boss or coworker). • Check in for a follow-up after making the delivery. This is the productivity side of working at home. But there’s another side to working at home that has been widely ignored. It’s the human side. There’s a story of three people who find themselves stranded on an uncharted desert island. Sort of like Gilligan’s Island, but without commercials. After years of learning how to smoothly work together to survive, the trio one day finds a bottle with a genie in it. The genie grants each person a wish. The first wishes to be back home in California, and—poof—she’s gone. The second wishes to be reunited with his family in Texas, and—poof—he’s gone. The third person looks around the empty island and says to the genie, “You know, I miss my two friends. I wish they were back.” Here’s the rest of the story about the Chinese workers. After nine months of working at home, the study was over. The workers were told they could continue working from home four days a week or they could come back and grind it out in-office for the full five. Slightly more than half of these workers wanted to come back and work in the office. They reported they were too “lonely.” There’s a human side to working at home. We can use our VitalSmarts tools to strengthen our communication muscle and our productivity muscle, but we might still feel like something is missing. Leaning in (versus spacing out) during meetings might help, and checking in or following up after finishing a project piece might help. But this human solution will need some personal thought and personal tailoring for each of us. If we’re feeling restless after 4 days at home, the human side is where we might want to look. And maybe call your brother “just because.” |

Welcome...Fun, useful, or wacky experiences about getting tenure, teaching better, publishing more, and having an incredibly rewarding career.

Categories

All

Some Blog ShortcutsArchives

September 2020

|

RSS Feed

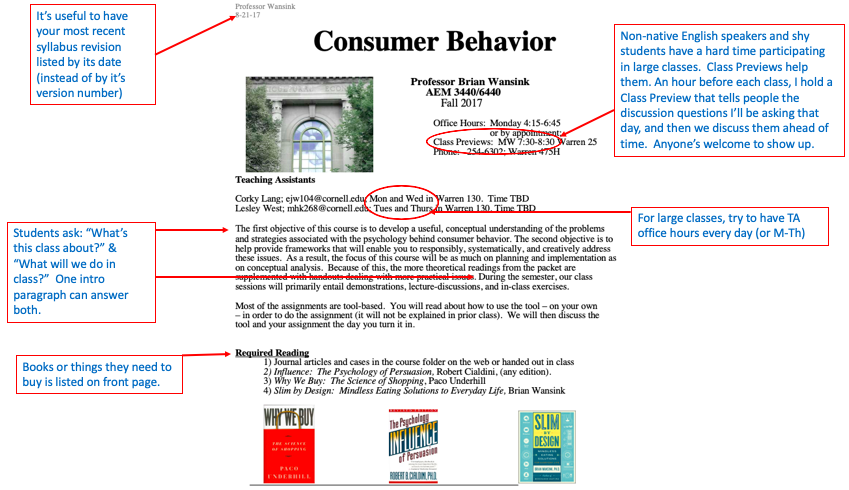

RSS Feed