|

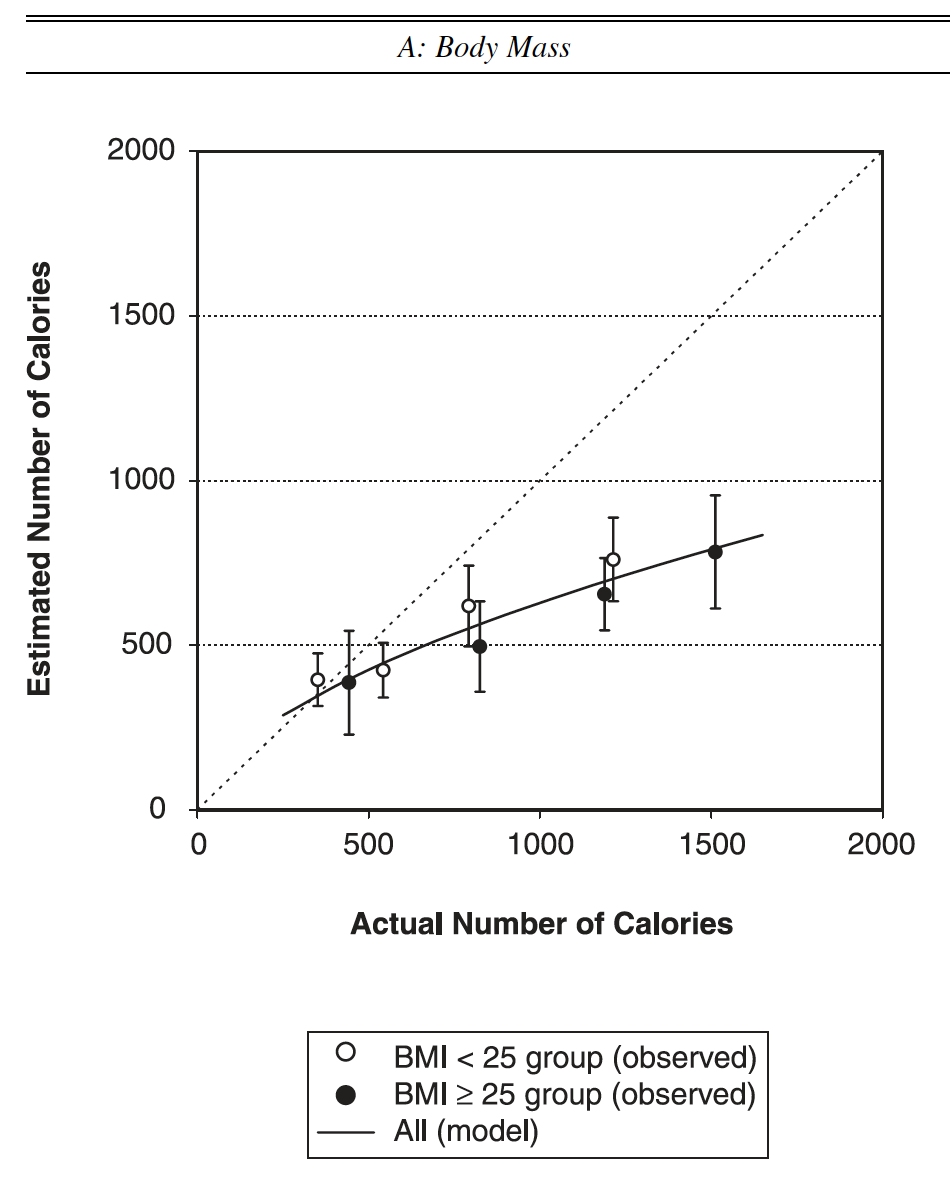

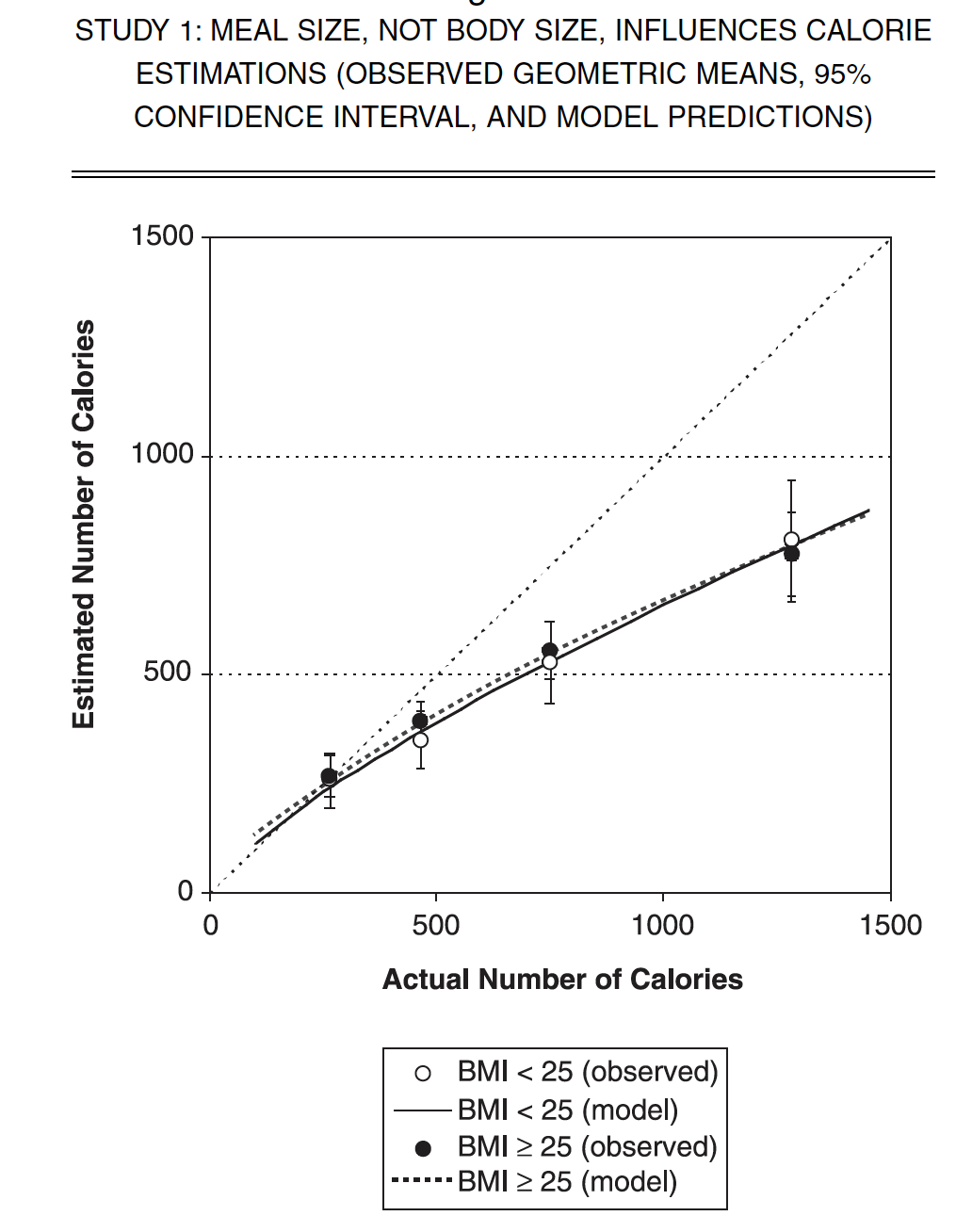

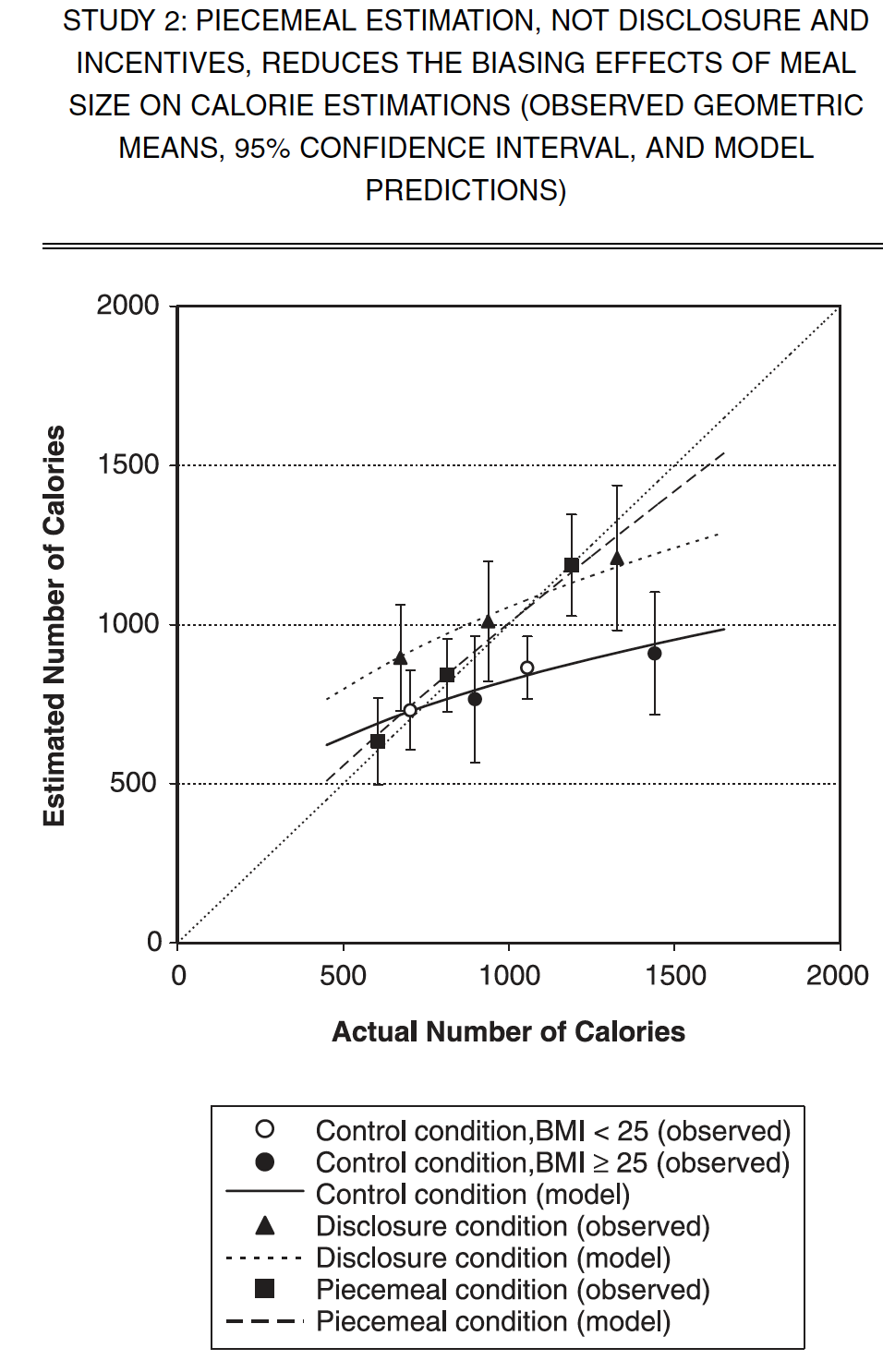

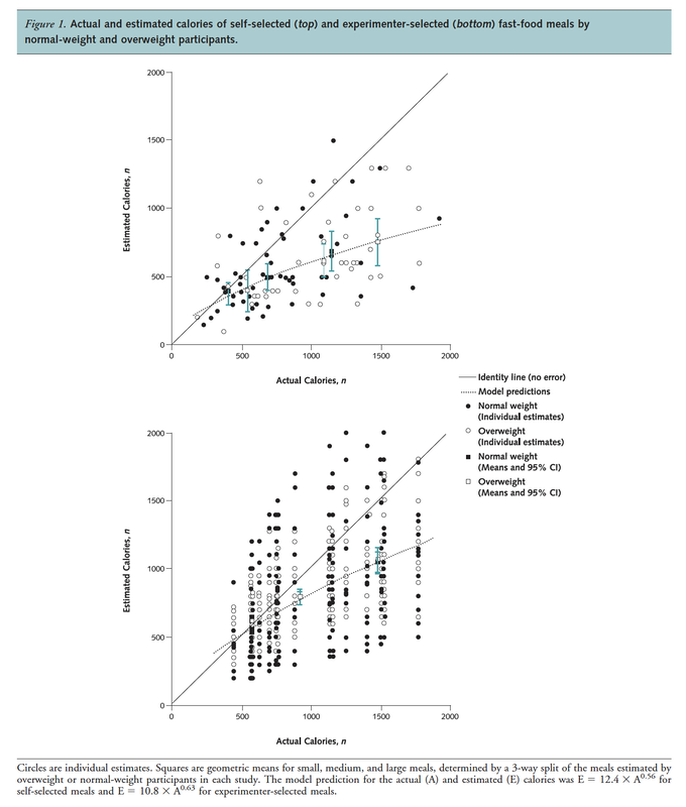

Could we better gauge how much we eat if we counted calories? Maybe not. Our experience with thousands of people suggests that most of us are terrible at estimating how many calories we have eaten so far today, or yesterday, or last week. On average, we generally think we have eaten 20% less than we actually do.[i] Those three pieces of pizza you thought were 1000 calories were actually 1200, and that 200-calorie donut was actually 240. But the real concern is with overweight people. They typically underestimate how much they eat by 40%. They think they eat about half as much as they really do. This has been a mystery. Scientists, physicians, and counselors have often blamed overweight people as trying to fool others (or themselves) about how much they are eating. Consequently, some dieticians, physicians, and family members blame and even berate overweight people as “lying” or “being in denial” as to how much they really ate. Hurtful accusations like these only make diet counseling effective at scaring overweight people off rather than changing them.[ii] Over the years we have had some overweight people in the Food and Brand Lab. Counter to what the experts say, these people always seemed to be pretty accurate at estimating the calorie content of all sorts of different foods. They were certainly no less accurate than the skinniest people in the lab. This was just the opposite of what all the classic scientific studies report. Why? To better understand this, we teamed up with a clever French researcher and good friend, Pierre Chandon. Together we discovered an important key to this mystery in research in an area called psychophysics. It seems that when estimating almost anything – such as weight, height, brightness, loudness, sweetness, and so on – we consistently underestimate things as they get larger. For instance, we will be fairly accurate at estimating the weight of a 2 lb. rock but will grossly underestimate the weight of an 80 lb. rock. We will be fairly accurate in estimating the height of a 20 foot building but will grossly underestimate the height of a 200 foot building. Chandon believes this is the key to the calorie mystery. At high levels all of us – normal weight and overweight alike – underestimate calorie levels with mathematical predictability.[iii] The secret to this mystery may not in the size of the people, but in the size of the meal.[iv] The bigger the meal, the less accurate we all are at estimating how many calories it has. To test this idea, we started in the lab and moved to a food court. First, we recruited 150 people who were either normal weight or obese. We then bought a dozen different meals of all different types – small sandwiches, huge sandwiches with chips, small chicken dinners, large chicken dinners with fries and a 32 ounce Coke, and so on. We asked each person to estimate the number of calories in each of the 12 meals. The results were alike, regardless of a person’s weight. The smaller the meal, the more accurate people are at estimating its calorie-level. The larger and larger the meal, the fewer and fewer calories they thought it contained. Everyone estimated huge 2000 calorie meals as only having 1200 calories or so. There were no differences in the estimates of the skinniest people or of the largest people. If normal weight and overweight people are equally biased in their estimates of calories, why is it that overweight people are almost always off by 40%? We ran a second study in a number of food courts to find out why. In these food courts, we asked 200 people randomly selected people what they had for lunch and how many calories they thought they ate (and drank). The more people had eaten, the less accurate they were. Someone eating a small, 300 calorie hamburger and a salad would underestimate the calories by about 10%, but someone eating a 900 calorie Monsterburger would underestimate it by a whopping 40%. It did not matter whether the person was skinny or huge, male or female, the bigger the meal, the less they thought they ate. It is “meal size,” not “people size” that determines how accurate we will be at estimating how many calories we have eaten. That popsicle-stick skinny person eating a 2000 calorie Thanksgiving dinner will underestimate how much they have eaten by just as much as the heavy person eating a 2000 calorie pizza dinner. The trouble is that the heavy person tends to eat a whole lot more of these big meals. It's meal-size, not people-size. References

[i]This gap in our calorie estimation and the exaggerated gap among obese peole has been widely reported by top scholars over the past 20 years. The classic studies include: David Lansky and Kelly D. Brownell, "Estimates of food quantity and calories: errors in self-report among obese patients," American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (1982), 35:4, 727-32. Steven W. Lichtman, Krystyna Pisarska, Ellen R. Berman, Michele Pestone, H. Dowling, E. Offenbacher, H. Weisel, S. Heshka, D.E. Matthews, S.B. Heymsfield, "Discrepancy Between Self-reported and Actual Caloric Intake and Exercise in Obese Subjects," New England Journal of Medicine (1992), 327:27, 1893-1898. M. Barbara E. Livingstone and Alison E. Black, "Markers of the Validity of Reported Energy Intake," Journal of Nutrition (2003), 133:3, 895S-920S. Janet A. Tooze, Amy F. Subar, Frances E. Thompson, Richard Troiano, Arthur Schatzkin, and Victor Kipnis, "Psychosocial Predictors of Energy Underreporting in a Large Doubly Labeled Water Study," The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2004),79:5, 795-804. [ii]Shirley S. Wang, Kelly Brownell, and Thomas Wadden, “The Influence of the Stigma of Obesity on Overweight Individuals,” International Journal of Obesity (October 2004), 28:10, 1333-1337. [iii] This is mathematically predicted by a compressive power function. The math is so painful, it even makes me weary. Anyway, the details (including the math) can be found in the very dense and very cool following article in one of the top journals in this field: Pierre Chandon and Brian Wansink, “Obesity and the Calorie Underestimation Bias: A Psychophysical Model of Fast-food Meal Size Estimation,” Journal of Marketing Research, (2006).

0 Comments

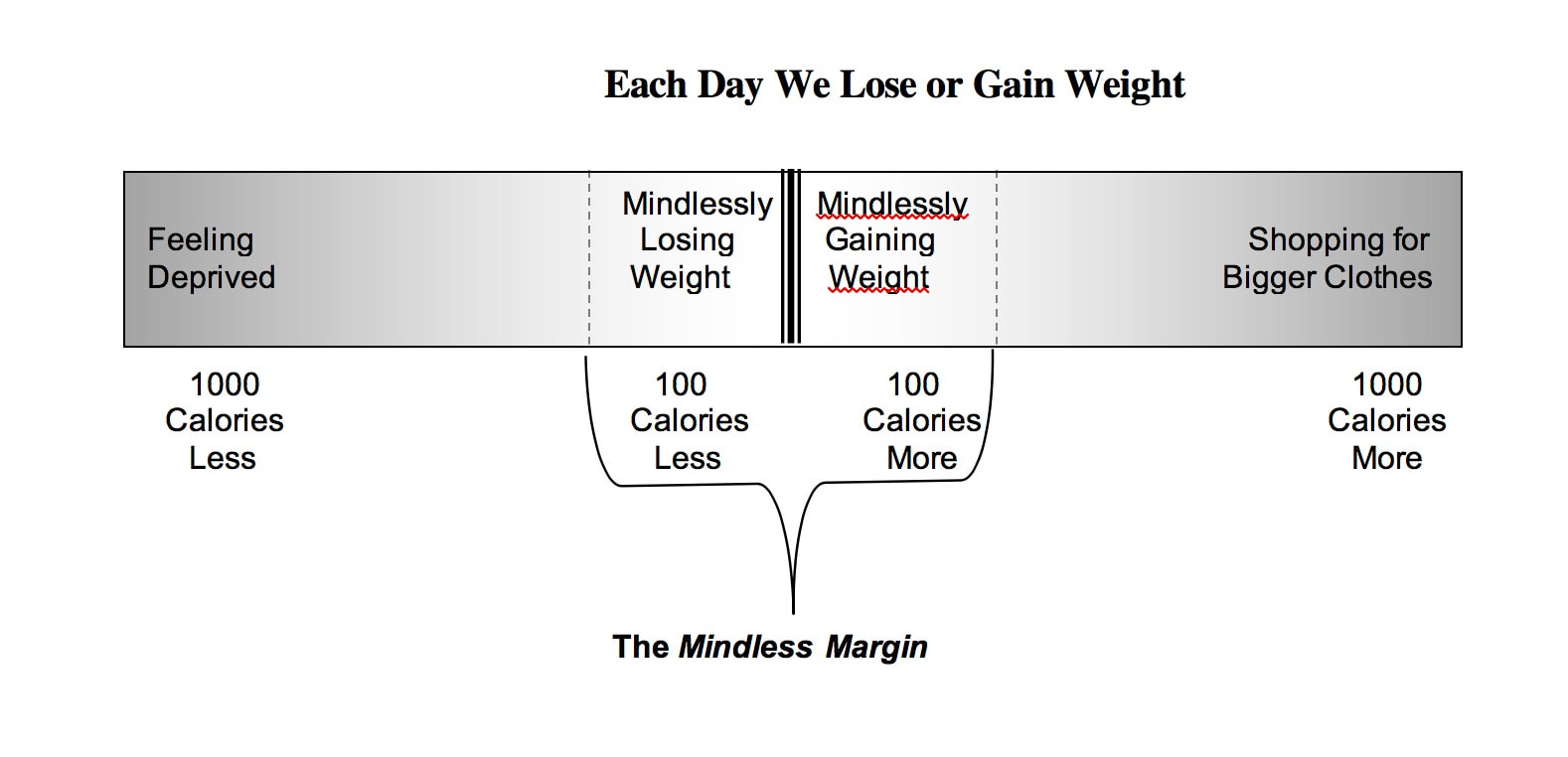

No one goes to bed skinny and wakes up fat. Most people gain (or lose) weight so gradually they cannot really figure out how it happened. They do not remember changing their eating or exercise patterns.[i] All they remember is once being able to fit into their favorite pants without having to hold their breathe and hope they can get the zipper to budge. Sure, there are exceptions. If we gorge ourselves at the all-you-can-eat pizza buffet, then clean out the chip bowl at the Superbowl party, then stop by the Baskin-Robbins drive-through for a “Belly Buster” Sundae on the way home, we realize we have gone too far over the top. But on most days we have very little idea whether we have eaten 50 calories too much or 50 calories too little. In fact, most of us would not know if we ate 200 or 300 calories more or less than the day before. This is the Mindless Margin. It is the margin or the zone in which we can either slightly overeat or slightly undereat without being aware of it. Suppose you can eat 2000 calories a day without either gaining or losing weight.[ii] If one day, however, you only ate 1000 calories, you would know it. You would feel weak, light-headed, cranky, and you would snap at the dog. On the other hand you would also know it if you ate 3000 calories. You would feel a little heavier, slower, and more like flopping on the couch and petting the cat. If we eat way too little, we know it. If we eat way too much, we know it. But there is a calorie range – a Mindless Margin– where we feel fine and are unaware of small differences. That is, the difference between 1900 calories and 2000 calories is one we cannot detect, nor can we detect the difference between 2000 and 2100 calories. But over the course of a year, this mindless margin would either cause us to lose ten pounds or to gain ten pounds. It takes 3500 extra calories to equal one pound. It does not matter if we eat these extra 3500 calories in one week or gradually over the entire year. They will all add up to one pound. This is the danger of creeping calories. Just 10 extra calories a day – 1 stick of Doublemint gum or 3 small Jelly Belly jelly beans – will make you a pound more portly one year from today.[iii] Only three Jelly Bellies a day. Fortunately, the same thing happens in the opposite direction. One colleague of mine, Stacy, had lost around 25 pounds during her first two years at a new job. When I asked how she lost the weight, she could not really answer. After some persistent questioning, it seemed that the only deliberate change she had made two years earlier was to give up caffeine. She switched from coffee to herbal tea. That did not seem to explain anything. “Oh, yeah,” she said, “And because I gave up caffeine, I also stopped drinking Coke.” She had been drinking about six cans a week – far from a serious habit – but the 139 calories in each Coke translated into 14 pounds a year. When she quit, she was not even aware of why she had lost weight. In her mind all she had done was cut out caffeine. Herein lies the secret of the Mindless Margin. This Mindless Marginis that small range where we make slight changes to our routine that we hardly notice. Nevertheless, these changes can have a gradual – but eventually big – impact on our weight. They can make the difference between being 10 pounds heavier next New Years Day or 10 pounds lighter. Cutting out our favorite foods is a bad idea. Cutting down on how muchwe eat is mindlessly doable. Many fad diets focus more on the typesof foods we can eat rather than how much we should eat. The problem is not that we order beef instead of a low-fat chicken breast. The problem is that the beef is often twice the size. A low-fat chicken breast that we resent having to eat is no better for our long-term diet than a tastier but slightly smaller piece of beef. If we are looking at only a 100 or 200 calories difference a day, these are not calories we will miss. We can trim them out of our day relatively easy – and unknowingly. The key is to do it unknowingly – mindlessly. In a classic article in Science,Drs. James O. Hill and John C. Peters showed that cutting only 100 calories a day from our diets will prevent weight gain in most of the US population.[iv]The majority of people only gain a pound or two each year, and their calculations showed that anything a person does to make this 100 calorie difference will lead most of us to loseweight. We can do it by walking an extra 2000 steps each day (about one mile), or we can do it by eating 100 calories less than we otherwise would. The best way to trim 100 or 200 calories a day is to do it in a way which does not make you feel deprived. It is so much easier to rearrange your kitchen and change a few eating habits so you do not have to think about eating less or differently. This is the silver lining to this dark, cloudy sky. The same things that lead us to mindlessly gain weight can also help us mindlessly lose weight. How much weight? Unlike the 3:00 AM infomercials, it would not be 10 pounds in 10 hours, or 10 pounds in 10 days. It is not even going to be 10 pounds in 10 weeks. You would notice that, and you would feel deprived. Instead, suppose you stay within the Mindless Margin for losing weight and trim 100-200 calories a day. You would probably not feel deprived, but in 10 months you would be in the neighborhood of 10 pounds lighter. It would not put you in this year’s Sports Illustratedswimsuit issue, but it might put you back in some of your “signal” clothes, and it will make you feel better without costing you bread, pasta, and your comfort foods. The theme of Mindless Eatingis that there are many things around us that manipulate or deceive us into eating more than we otherwise would. Popcorn buckets manipulate us, names confuse us, plates deceive us, friends unwittingly lead us astray, lighting and music fool us, colors miscue us, shapes trick us, and on and on. But all of them do so very subtly. Mindless Eating helps you generate mindlessly-easy solutions to trim excess calories out of your life in a way in which you will not miss them. Each chapter specifically illustrates what researchers know about mindless eating, and each shows how you can use the same tricks to reverse how much you eat. There are a lot of invisible traps out there that we unknowingly let trick us into overeating. What you can do is outlined in the next chapters, but we are first going to look at what causes us to decide how much we want to eat. Once we understand why we eat how much we eat, we can more clearly see how to change it. References

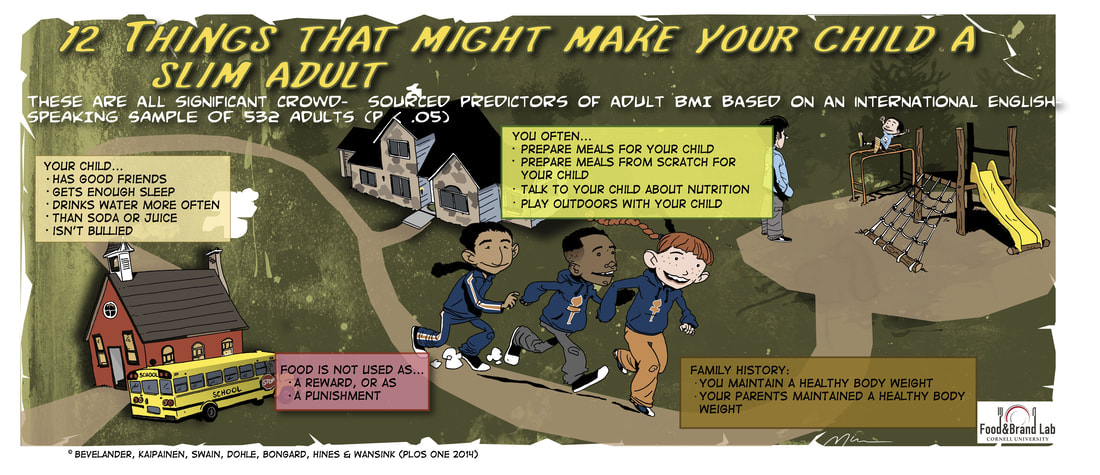

[i]N. E. Sherwood, Robert W. Jeffry, Simone French, et al., “Predictors of Weight Gain in the Pound of Prevention Study,” International Journal of Obesity(April 2000), 24:4, 395-403. [ii]If you burn off the same number of calories each day as you eat, you are “in energy balance.” The exact number of calories you need to be in energy balance varies depending on your weight and how much you move during the day. Smaller adults burn fewer calories a day than larger adults; active people more than inactive people. [iii]A pound is roughly equivalent to 3500 calories. Eating three Jelly Belly jelly beans a day (12 calories) would lead to are 4380 over the year. Similarly drinking one less can of Coca-Cola (139 calories) each day would amount to 101,470 calories – 29 lbs. – over a 2 year period. [iv] Details can be found in James O. Hill and John C. Peters (1998), “Environmental contributions to the obesity epidemic,” Science, 280 (5368): 1371-1374. [v]This person, Jay S. Walker, also supplemented this with lots and lots of exercise. We sometimes hear that a child “inherited” their sweet tooth, or their love for vegetables, or for spicy foods from a parent. Although the genetics jury is still out, it is clear that children adopt some of their mother’s tastes when they are still snoozing away in the womb. For instance, pregnant women who drank carrot juice in their last trimester significantly increased how much their children preferred carrot-flavored cereal months later.[i] Not only do they develop prenatal munchie preferences, children also start learning what they like and don’tlike before they are four months old. They do this by picking up on signals a parent or caretaker unconsciously gives about whether a food is tasty or not. This was first discovered in the Massachusetts Reformatory for Women during the 1940s. The women incarcerated here were able to keep children under 3 years of age and to frequently visit them and their carekeepers in the nursery. Records were kept on what the children ate, so it became suspicious when all of a sudden their juice preferences abruptly changed. The psychologist at the reformatory, Sibylle Escalona, began to suspect that the caretakers were unconsciously influencing what the children preferred.[ii] Her report starts out, “It came to attention accidentally that many of the babies under four months of age showed a consistent dislike for either orange or tomato juice.” She then went on to report that babies who had refused to drink orange juice for about three weeks would all of a sudden turn into orange juice lovers within two or three days. She traced these abrupt changes to changes in caretakers. Upon being interviewed, it was found that a couple of the new carekeepers had a strong preference for orange juice and a dislike for tomato juice. Somehow this was passed along to the four month infants. But how? Interestingly, even two-day-old babies are thought to be able to imitate facial expressions of adults.[iii] It could be that these caretakers subconsciously showed subtle signs of acceptance or rejection based upon what they personally felt toward the foods. A fleeting smile or grimace might go a long way toward explaining why one baby has daddy’s sweet tooth and another has mommy’s love for vegetables. This also makes good sense that people feeding babies pretend to taste the food (Mmmm . . . yummy!”) and to open their mouths and play “airplane hanger” when feeding the little tykes.[iv] Escalona’s accidental discovery has aged well. Watching someone smile or grimace when eating food scares elementary children away from even an otherwise tasty food.[v] And this also works with being friendly – you can attract more children to new foods with honey than with vinegar. When a friendly adult repeatedly gave children either canned unsweetened pineapple or cashews, they quickly learned to like this food more than when it was given to them by a less friendly adult.[vi] It is not only our tastes that our children can inherit. It can also be our attitudes about food and eating. In one Yale study of normal weight one-year olds, mothers who were highly preoccupied with weight issues were more likely to be erratic in their behavior during meals. Sometimes, they urged their one-year-olds to eat more, sometimes to eat less, and sometimes they rushed their feedings. They were also much more emotionally aroused when feeding their babies compared to mothers who were not concerned with weight issues.[vii] Children see this anxiety and these food obsessions at a tender tabla rosa age. Just as our children can inherit our eye color and hair color, they might also be behaviorally imprinted with our obsessions with food or with weight. Fortunately, when they start to talk we can even more quickly imprint a passion for balanced meals, smaller portions, vegetables, and fruits.[viii]

References

[i]A good example of the power of availability is Marsha D. Hearn, Tom Baranowski, Janice Baranowski, Colleen Doyle, Matthew Smith, Lillian S. Lin, and Ken Resnicow, “Environmental Influences on Dietary Behavior Among Children: Availability and Accessibility of Fruits and Vegetables Enable Consumption,” Journal of Health Education(1998), vol. 29, pp. 26-32. [i]See Julie A. Mennella and Gary K. Beauchamp, “The Early Development of Human Flavor Preferences,” in Why We Eat What We Eat: The Psychology of Eating, ed. Elizabeth D. Capaldi, Washinton, DC: American Psychological Association, 1996. [ii]This is a classic: Sibylle K. Escalona, “Feeding Disturbances in Very Young Children,” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry(1945) 15:76-80. [iii]T.M. Field, R. Woodson, R. Greenberg, and D. Cohen, “Discrimination and Imitation of Facial Experssions by Neonates,” Science, (1982) 218:179-181. [iv]Thanks to Alexandra Logue for this example from her incredible book, The Psychology of Eating and Drinking, 3rdEdition, (New York: Brunner-Routledge, 2005). [v]F. Baeyens, D. Vansteenwegen, J. De Houwer, and G. Crombex, “Observational Conditioning of Food Valence in Humans,” Appetite,(1996) 27:235-250. [vi]Much of the most interesting research in this area is by LeAnn L. Birch. See, “Generalization of a Modified Food Preference,” Child Development, (1981), 52:755-758. [vii] Pike and Rodin , "Mothers, Daughters and Disordered Eating", Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 1981. [vii] B Wansink, Mindless Eating: Why we eat more than we think, p. 168-171. [xi] Excerpted from the American Dietetic Association’s excellent book, Dieting for Dummies (Wiley, 2004). Your stomach can’t count calories.

It can’t count the number of spoonfuls of Golden Grahams cereal you had for breakfast. It can’t count the number of ounces in the overpriced Frappuccino you drank on the way to work. It can’t count the number of french fries you inhaled in the first 90 seconds of your lunch break. It doesn’t know how many scoops of the aptly named Chubby Hubby ice cream (a whopping 330 calories per half-cup) you ate standing in the front of the refrigerator when you got home. Our stomachs just aren’t designed to keep accurate track of how much we have eaten. If we could really see all that we’re putting in our mouths, we’d probably eat a lot less. Despite the cliché, our eyes are typically not bigger than our stomachs. In fact, our eyes are often better at telling us how much to eat than our bellies. That’s because it takes about 20 minutes after we eat before our stomach starts registering that we’re full. If you could look back and see all of the handfuls of potato chips you’ve already gobbled before shoveling in another, you’d likely hestitate before reaching back into the bag. But we’re hungry! We can’t count on our memories to help us, either. Take the popular but diet-destroying all-you-can-eat buffet.In a study in the journal Perceptual and Motor Skills, my colleague Dr. Collin Payne and I promised a free chicken wing buffet to 52 graduate students (17 men and 35 women) while they watched the Super Bowl at a sports bar in Urbana, Ill. As part of the study, the waitresses were instructed to clear the dishes at only half of the tables. If people had their tables continuallycleared, they continually ate. Clean plate, clean table, get more, eat more. Their stomachs didn’t keep track of how much they’d eaten, so the students kept on eating until they thought they were full. Each of these people ate an average of seven chicken wings apiece. The students who did not have their table bused were less of a threat to the chicken population. After the game was over, they had eaten an average of two fewer chicken wings per person —that’s 28 percent less than those whose tables had been bused. The chicken-wing gobblers didn’t believe they were influenced by a clean table —they simply didn’t remember chowing down as much as they did. They claimed they ate so much because they were hungry. That’s the big danger of not having visual cues. Seeing is believing. Do yourself a favor —make sure you see the food before you eat and while you eat it. We find that when people put everything on their plate before they start eating —including, snacks, dinner or dessert —they eat about 14 percent less than when they take smaller amounts and go back for seconds or thirds. Instead of eating directly out of a package or box, put your snack in a separate dish and leave the box in the kitchen. You will be less likely to eat more and more ... and more.Whether you are eating chicken wings or cookies, you’ll eat less if you see what you’ve already eaten. The same is true for beverages —it’s easy to forget how much soda you’ve guzzled if there’s nothing to remind you. So keep your eye on the empties. For that matter, if you want to keep friends from overimbibing at your next dinner party, keep the empty wine bottles on the table and pour refills into fresh glasses without clearing the others. Not only will you spend less party time cleaning up, seeing the evidence of how much they’ve drunk could help your friends get home more safely. Guessing how many calories we ate in a meal is a dangerous game. Most of us terribly underestimate how much we eat –usually by up to 50%.

Think your sandwich and chips were about 400 calories? 750 is probably closer to the truth. In fact, we’ve shown that the bigger and bigger the meal, the less accurate we are in guessing how much we ate. There are two easy solutions. One is to take our best calorie guess –and then double it. We’ll be a lot more accurate than if we stick with our first estimate. The second solution is to separately estimate the number of calories in each item we eat –the sandwich, the chips, the soft drink –and then add them up. We’re a lot more accurate when we estimate small amounts of food than entire meals. Source: Pierre Chandon and Brian Wansink (2006) Journal of Marketing Research Does the idea of comfort foods conjure up a molten lava cake, ice cream sundaes, or three-pounds of salted peanuts?

In one of our studies, we found 40% of people’s favorite comfort foods are actually pretty healthy, meal-related foods –soups, steak, green bean casseroles, hamburgers, and so on. For most of us, there’s a small difference in how much we prefer unhealthy comfort foods compared to the healthier ones. Indeed, we find people who ate these healthier comfort foods rated themselves as more comforted, happier . . . and less guilty than those who indulged in the bad ones. Zapping a can of soup seems to go a lot farther than dishing up the mountain of ice cream. Source: Wansink, Brian, Matthew M. Cheney, and Nina Chan (2003), “Exploring ComfortFood Preferences Across Gender and Age,” Physiology and Behavior, 79:4-5, 739-747. This is a great question (and one of the subjects of Chapter 6 of Mindless Eating), but here's a quick example of how vegetables can make a meal tastier if they are served in the main dish and not off to the side.

A number of years ago I flew back for my Aunt Eileen’s 90th birthday party in Iowa. After a rousing out-of-tune rendition of “Happy Birthday,” and a round of Wal-Mart birthday cake, Aunt Eileen fell soundly asleep in her chair. It reminded me of most of my birthdays. Later that night we all had a tuna casserole dinner –a very good casserole dinner. But something was different. It didn’t have any rice, or potatoes, or pasta in it. What it had was a double-load of vegetables. Some were frozen, some fresh, some canned.Some were probably according to the recipe, but most were pretty much random. It didn’t matter; it tasted great. What an overlooked idea. These vegetables gave the casserole a whole lot more flavor than the blah-tasting carbs we put in by habit. We've used this every week since in my kitchen. If vegetables go in the dish, we make it a double-load and no one ever complains. A while back a manufacturing company wanted me to redesign their lunchroom so their employees could mindlessly eat better without realizing it (or rebelling). After we had finished our walk-through and questions, the President said, “I know, I know, we should get rid of all our vending machines.”

Absolutely not. If a company wanted revolt on their hands, they would get rid of vending machines. We all want to know we have choice, even if we don’t make the choice. What I suggested is that they take a number of the vending machines and offer some healthier options. For the rest of the machines, they can keep all of the tempting, chocolately goodies, but move them to corners of the factory floor that make them less accessible. People can still have them, but they have to want them bad enough to walk 200 yards instead of 30 yards. That’s just enoughfor them to pause and ask if that’s wantthey really want. Try this at work. You can still buy what you want from a vending machine or a snack bar, but you have to use the one that’s furthest from your office. Maybe even in a next building. Lose 33 lbs. by Drinking Coffee? A while back in Minnesota, I was giving a speech and I took a detour during the speech to talk about some of the seemingly strange changes in diets that have led to people losing large amounts of weight.

Afterward a woman in her early fifties excitedly told she had last 33 pounds in the past 6 months by making only one change: She started drinking black coffee. More accurately, she had started drinking black coffee because she had stopped drinking it with cream and sugar. Of the hundreds of small changes people have told me about that have helped them lose 25 lbs or more in less than a year, this was a first. When I was back at the hotel, I did a little math. Unless this woman drank over 7 cups of coffee a day (a possibility), the math didn’t add up. What I suspect happened was that she did make this cream and sugar change. But this cream and sugar change probably also led to her making other changes that were less obvious to her. It might have given her less of a sweet-tooth or less of a reason to sit down for a snack. When I was doing a radio talk show one night a caller said, “I constantly ‘co-eat.’ I nibble when I watch TV, when I’m on the computer, when I’m reading and when I have friends over. What can I do about this?”

We’ve worked with a number people who have been vexed with this, and there are two general approaches that can help. Onedeals with behavioral substitution and the other one deals with behavioral interruptions. First, a person can try and substitute a different (or healthier) behavior for their snacking. We’ve recommended people buy those big trays of pre-cut veggies from the story and nibble on these. Not only are they a bit healthier, but they also give a person to break a habit other than going “cold turkey”. That is, they are less reinforcing that eating malted milk balls or chips and so eventually –if a person wants –they can ease themselves away from the veggies to nothing.(Chapter 7, “In the Mood for Comfort Food” in my book Mindless Eating gives more ideas about how to use substitution to work for you.) The second approach is to stopping co-eating or hand-to-mouth munching is to find some way to interrupt the behavior. If people don’t want to use the substitution method we suggestthey use thisapproach. They put a loose-fitting rubber-band on each of their wrists. Anytime the snack, they need to snap the rubber-band on the hand they snacked with. This does two things. First, it makes us aware of everytime we snack. Second, it makes us have to “pay” for something that tastes good with something (the snap) that hurts a little. Before long people tell us they simply decide to leave the chips in the kitchen and not bring them into the TV room. “My husband always wants me to make him cookies, but it ruins my diet. What can I do?”

Set aside an out-of-the-way cupboard that you identify as his and that you make off-limits to you. For some, this can be the top shelf of that cupboard way on the right hand side of your kitchen that you seldom open anyway. You can have your husband store his cookies, chips, and whatever in here. One advantage of having an “off-limits” cupboard is that it removes the “tyranny of the moment.” It removes the temptation you would have to say, “OK, only this once.” In effect, because it’s off-limits, any thought about eating those snacks ends with the answer “no.” It’s the same reason the Atkins diet was successful with many people in the short-run. It provided and black and white answer of what could be eaten. See if you and your husband can agree on the top-shelf of a cupboard. The two not-so-magical secrets of losing weight are eat less and move more. For most people, it’s a whole lot easier to eat a little less than to move a little more.

Consider the Four Mile Donut. If we were to walk as fast as we could for an hour, we’d cover a breathless, heart pounding 3-4 miles. If we then decided to celebrate our workout with coffee and a donut, we would eat more calories in a minute than we burned off in an hour. People who often start exercise programs claim to gain weight in the first couple weeks. My Food and Brand Lab has started investigating what we call Calorie Compensation. We’re finding that almost all of usbelieve that we burn more calories exercising than we actually do. The problem is that after we excerise we often try to reward ourselves with that pint of Ben and Jerry’s, and that’s where things go wrong. If we pat ourselves on the back, we should also pat ourselves on the stomach because that’s where all those calories are going. Exercising is an important part of our life and of good health other than just our weight. But for most of us, it will probably be easier to eat one less donut today than to walk four more miles. One guideline I recently learned was that 30% of weight loss comes from the gym and 70% from the kitchen. Using only two words, I bet I could get you to overeat a snack you don’t

even really like. Those two words would be “low fat.” We’re living in a world of fat-free, carb-free and sugar-free snacks. Most of the time, if we think they are at least low fat, we think “it must be good for us” —even if the snack is loaded with sugar. When Nabisco came out with SnackWell’s, a line of no-fat and low-fat cookies and crackers, they flew off of shelves, gobbled up by the people who believed they could eat them until they magically whittled down into a supermodel. Six months later and about 6 pounds heavier, the low-fat fanatics finally realized that these cookies had about only 30 percent fewer calories than regular cookies. This happens all the time. Often the fat-free version is not much lower in calories than the regular version. For example, each low-fat Oreo cookie has 50 calories. The regular version has just over three calories more.Low-fat labels can lead us to mindlessly overeat a product with guilt-free abandon. Take granola. Where low-fat granola is indeed lower in fat, it is only about 12 percent lower in calories. It does not take a lot of mindless munching to scarf down an extra 12 percent of granola, especially while thinking you are doing your body good. In one study, a French colleague, Pierre Chandon, and I invited people to watch some commercials and a video episode of the “Dukes of Hazzard.” We gave them bags of granola that were labeled as either “Low-fat Rocky Mountain Granola” or “Regular Rocky Mountain Granola,” as we described in the Journal of Marketing Research. In reality, all of the granola was low fat. While people watched the video, they ate the granola. Those given what was labeled as low-fat granola kept munching long after the other group stopped. After the movie, we weighed the remaining granola to see how much had disappeared. It turned out that those eating what they thought was low-fat granola ate 35 percent more, which translated into 192 more calories. When we offered them low-fat chocolate, they loaded up on 23 percent more calories. The low-fat label tricked people into eating more than if the product had a regular label. The cruel twist is that these labels can have an even more dramatic impact on those who are overweight. People who are overweight and eat more than their thinner peers are in danger of really over-indulging when they see something with a low-fat label. The problem is that when we are looking for an excuse to eat something, low-fat labels give it to us.What’s worse than overeating a snack?Overeating one we don’t even really like that much. Few low-fat snacks are nearly as tasty as their regular version.So rather than overeating something you don’t even really like, enjoy the regular version —but only half as much of it. This morning I was asked how a person can break a “brand bond” (say drinking 9 Cokes every day, or eating Ben & Jerry’s every afternoon).

Cold turkey is one option, but what is more empowering is to set up trade-offs that still give a person a feeling that they can consume it IF they want, but which just makes it more of a hassle to do so. For example only allowing yourself to bring single Cokes into the house. This way you’re forced to ration it to when you really, really need it, or to make a trip for another. This can also be done in the form of, “I can have my Coke-fix, but only if I ______ (work out, clean the kitchen, clear out my email inbox, etc.). A second way is through brand substitution. Enable yourself to have all you want (or better yet, half of what you want) but of another brand that you don’t enjoy as much. That has been successful in breaking the cycle for some. A great book on this general topic is called “Breaking the Pattern” by Charles Stuart Platkin. (You might recognize his name through his syndicated column called “The Diet Detective.”) What day of the week did you start your most recent diet? Chances are it was a Monday.

Forty-six percent of people in our recent study said their last attempt to launch a weight-loss plan started on a Monday morning. Now, do you remember when you called it quits on that dieting attempt? For 31 percent of people, the miserable experience is over by Tuesday evening. Like most New Year’s resolutions, Monday morning diets are doomed despite our very best intentions. That’s because both are based on deprivation. No matter what you’re denying yourself —carbohydrates, fat, red meat, snacks, pizza, breakfast, chocolate —you are setting yourself up for failure. It doesn’t make much difference whether we are deprived of affection, vacation, television or our favorite foods. Being deprived of what we enjoy most is no way to live. It puts our nerves and our willpower on a hair trigger. Instead, go back to where it all started. Beware creeping calories. No one goes to bed skinny and wakes up fat. Most people gain (or lose) weight so gradually they cannot really figure out how it happened. They do not remember changing their eating or exercise patterns. All they remember is once being able to fit into their favorite pants without having to hold their breath to getthe zipper to budge. This is the danger of creeping calories. Just 25 extra calories a day —1 Hershey’s Kiss or 5 M&Ms —will pack on 2 extra pounds of paunch one year from today. Only 5 M&Ms a day. Fortunately, the same thing happens in the opposite direction. One colleague of mine lost about 25 pounds during her first two years at a new job. When I asked how she lost the weight, she could not really answer. After some persistent questioning, it seemed that the only deliberate change she had made two years earlier was to give up caffeine. She switched from coffee to herbal tea. That did not seem to explain anything. “Oh, yeah,” she said, “and because I gave up caffeine, I also stopped drinking Coke.” She had been drinking about six cans a week —far from a serious habit —but the 139 calories in each Coke translated into about 12 pounds a year. When she quit, she was not even aware of why she had lost weight. In her mind all she had done was cut out caffeine. Small changes to your routine or to your environment can make a big difference. Nevertheless, making even three changes can have a gradual —but eventually giant —impact on our weight. They can be the difference between being 20 pounds heavier next New Year’s Day or 20 pounds lighter. What three changes should you make? There are hundreds to choose from, but the best ones fit your goals, your lifestyle, and they will probably change each month. Pre-plate the high-calorie foods in the kitchen and leave the leftovers in the bowls in the kitchen. Do not serve what some call, “fat-family” style, unless it’s the veggies and salad. Allow yourself an afternoon snack only if you’ve first eaten a piece of fruit.Use the half-plate rule: At dinner, load up the right side of your plate with salad, fruit, or vegetables. The other side can be starches and meat. When you no longer obsess over what you’re not eating, you’ll find it easier to improve your diet and lose weight. The best diet is the one you don’t know you’re on. Hungry for a Super Bowl victory? The Super Buffet table may end of having the last laugh. The only thing I love more than the commercials is the food.

The Super Bowl ranks #1 in terms of home parties (it even beats New Year’s Eve), and it ranks #2 in food consumption, according to Mindless Eating (p. 38). In 2004, Super Bowl partiers ate 4,000 tons of popcorn, 14,000 tons of chips and an estimated 3,200,000 pizzas. In a cute study we have coming out next month in the psychology journal “Perceptual and Motor Skills” (cool journal, boring name), we show even the food you see when you watch the Super Bowl can lead you to ‘Blimp’ out. In a Champaign, IL sports bar, a couple of years ago, we treated 53 Super Bowl partiers to all-you-can-eat chicken wings buffet. The party was actually a study, and during the game waitresses bussed the chicken bones from halfof the tables, or they let them pile up on people’s plates. Sports fans eating off of clean plates ate 43% more chicken wings than those whose bones stayed on their plates. These left-overs served as boney reminders of how much they had eaten. This kept them from mindlessly eating more. In general, it is important to have some idea of how much you have eaten. Serve yourself onto a plate, and then stop when the plate is empty. Again, dish it out, eat it slowly, and stop. We did a set studies in movie theaters, holiday receptions, and homes, we showed we eat an average of 28% more total calories when they eat low-fat snacks than regular ones. Low-fat foods are not always low-calorie foods becasue fat is often replaced with sugar.

When we see a low fat foot we basically think we’re eating fewer calories and we think we’ll feel less guilty. That’s the precise recipe for overeating. Although low fat snacks taste OK, I never think they taste as good as the real deal. When we discovered this tendency to overeat low-fat snacks by 28% (it goes up to 45% more for obese people), most of the people in my Lab made the the following change. We stick with the regular version, but eat a little bit less. It’s better for both your diet and your taste buds. After one of my Mindless Eating presentations , someone asked, “What is the best way to be mindful about how we eat?”

Being mindful or aware of how we overeat isn’t the answer for most of us. We’re too busy, too stressed, and have too much on our mind already. On top of this the eating cues around us are simply too powerful to resist and we don’t want it to be a full time job. The key is to simply rearrange –re-engineer –our environment so we mindlessly eat less and enjoy it more. If you serve more onto big plates, get rid of them. If a nearby candy dish on your desk leads you to eat twice as many candies (it does), move it 6 feet away. The best place to start with re-egineering is with your biggest diet danger zone: 1) Meal stuffing, 2) snack grazing, 3) restaurant indulging, 4) party binging, and 5) desktop/dashboard dining. Most people only have one or two of these that is the most problematic. Start with making small changes. You can then mindlessly eat better. First sentence in Mindless Eating says, “The best diet is the diet you don’t know you’re on.” The key is in being positively mindless. A number of years ago I heard someone say that gratitude and depression cannot co-exist. I’ve thought about this on a number of occasions since then and the same seems true with any other negative emotion —disappointment, regret, lonliness, or frustration.

It’s impossible to be thankful about any aspect of our life (such as our food, family, eyesight, or computer) and for that to not shine some light on our day. In 75 years we’ve gone from depression breadlines and wartime rationing to affordable, convenient, great-tasting food cooked (or at least heated up) by loving hands. There are 364 other days in the year. Thanksgiving is the day we can give ourselves a license for Mindless Eating —and to be thankful for it. Have a Grateful Thanksgiving. It’s 9:45 and all you can think about is pasta, cake, or popcorn? This might have an easier solution than chaining yourself to your couch.

I was recently up in Canada shooting a segment for the Discovery Channel. During a break, the hostess all of a sudden asked —kind of out of nowhere —“How can avoid my midnight carbohydrate binges?” As I show in Mindless Eating, most of the food cues that cause us to overeat can be easily – mindlessly – reversed. This carbo craving, however, might be more physiologically-driven than psychologically-driven. A while back there was a study show that middle-aged women who are low in vitamin B, were more likely to experience serious nighttime carb cravings than those who regularly took a vitamin. Low vitamin B might explain some part of the empty pasta bowl. For the rest of us – young, old, or male – we might also want to make sure to pop our multi-vitamin (or B-complex vitamin) in the morning. It’s better than having to chain ourselves to the couch. A while back I was in Montreal to give a talk at a Childhood Obesity conference. At breakfast that day, someone approached me and shared that they had picked up Mindless Eating and had already instituted their 3 small changes —one involving breakfast.

The key to reversing Mindless Eating is to not get too ambitious. Small changescan be mindless, and that’s the way they should stay. A good rule of thumb is that if you have to think about them too much, you’re probably biting off too much. Don’t expect to see the scale tip after a few days. Most of us gain weight at a rate of 25 extra calories a day. With your Three Changes, you’re trimming them down at the rate of about 300. That’s only 1/11 of a pound a day, but it’s 30 lbs over a course of a year. To keep things varied, you might want to choose three other Mindless Margin changes at the end of November. It will break things up, and you can tailor them more for the holidays. Here's the magic of trying to make three consistent daily changes. If you only make one change, you might be losing weight too slow to stay motivated. If you make five changes, you won't be able to keep track of them and people report its too easy to fall off the wagon. One of the five Diet Danger Zones that trip most people up is "Party Binging." Parties can be especially merciless on us because of the variety, convenience, and distractions they provide.

Nearly all of my answers to these FAQs are based on scientific, published research my Lab and I have conducted on food and behavior. Sometimes, however, I like to add ideas and tips --sometimes untested --that readers of Mindless Eating have passed on. For instance, every few months I ask visitors to share their ideas of what they mind most useful to prevent them from overeating --such as in one of the five Dietary Danger Zones like Party Binging. When asking about Party Binging a few months ago, there were over 150 different ideas people mentioned. A lot of them were pretty standard, but a lot of them were really unique. Here are the ones most frequently given: • Eat a healthy meal before I go to the party so as to not arrive hungry • If it doesn’t taste as good as I thought, I don’t swallow it • Drink plenty of water during the party (with ice and citrus twist to make it look like a real drink)I try not to eat at parties at all to stick to my planned schedule of when to eat • Don’t drink alcohol because it makes me want to eatMake sure you don’t stay in the room with the food • Don’t go back for seconds • Keep in forefront of mind how long I will need to exercise if I eat tons of calories • Focus on talking to people instead of the food and always keep a crowd around me These all won't work for everyone, but if a couple will work for you at the next party, try them out. There were a whole lot of real creative things people did, but we'll save those for another party day. A while back I had the chance to speak at the South Beach Wine and Food Festival in Miami. I was asked to go talk about some of our recent studies on Just returned from the South Beach Wine and Food Fesitival in Miami. I was asked to go talk about some of our recent studies on how involving children in cooking influences what they eat.

A huge proponent of teaching kid’s to cook is Food Network’s, Rachel Ray, who’s started a foundation with this purpose. After she talked about the importance of cooking in her childhood, I was to share present some of the evidence as to how involving your kids in meal preparation influences. When children help prepare a meal, they become creators.They become less likely, then, to become a food critic. Its very hard for a child to “diss” something he or she helped create. Is there evidence that this actually changes a family meal? In a pilot study we recently finished at my Cornell Food and Brand Lab, we examined 119 households –half which encouraged their kids to help prepare family meals and half who didn’t. There were interesting differences. Families with junior food preparers were more likely to 1) eat as a family, 2) eat fruits and vegetables, 3) eat a salad, 4) offer a blessing, 5) drinkmilk, and 6) eat desserts. Part of what ids going on in some families is that bringing the kids into the kitchen also helps make the meal a bit more special than it otherwise would have been.What are ways you’ve encouraged your children to help out with a family meal? Are you smarter than a bowl? A nice snack mix in a big serving bowl will lead us to serve up to 50% more than the same snack in a smaller bowl.

At a Super Bowl party, we served Chex Mix to half of the partygoers in large gallon-size bowls. The other half were served from slightly smaller bowls. Those serving from the big bowls took and ate 146 more calories. Big bowls simply make it look normal and reasonable to serve more, so we do. The solution? When it’s your party, put the snacks in smaller bowls to begin with. The easiest way to outsmart a big bowl is to not bring it out in the first place. Source: Wansink, Brian and Matthew M. Cheney (2005), “Super Bowls: Serving Bowl Size and Food Consumption,” JAMA–Journal of the American Medical Association,293:14 (April 13), 1727-1728. Do you want to make that New Year’s Resolution “stick” this year? The key might be as simply as making sure you do it for at least 25 days.

In our National Mindless Eating Challenge study, people were asked to make one small change –such as not eating with the TV on or eating off a small dinner plate –for as many days as they could for one month. Those who made their change for25 or more days were three times more likely to lose weight than those who did it for only 20. Just “doing it” works better than thinking about it. It’s too easy for today to the an exception. Source: Presented at the Experimental Biology Conference in Anaheim, CA in April 25. The forthcoming abstract will be published as: Patterson, Richard Wells and Brian Wansink (2011), “Decoupling the Independent Effects of Multiple Simultaneous Behaviors,” FASEB Journal, 2:878.7, forthcoming. |

The Mission:For 30 years my Lab and I have focused on discovering secret answers to help people live better lives. Some of these relate to health and happiness (and often to food). Please share whatever you find useful.

Blog Categories

All

|

||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed