|

Every New Years Day, millions make the resolution to “eat less and lose weight.” Within a three days, growling stomachs and headaches lead a lot of these people to fall off the weight-loss wagon.

We did a study on habits that investigated people who wanted to make it a habit of eating more of something. This could have been more vegetables for dinner, more whole grains at lunch, more fruit as snacks, more hot (versus cold breakfasts), and so on. People who made it a happen to eat more of healthy foods (instead of eating less of unhealthy foods), reported losing a little over 1 extra pound a month. What is the one way you could “Eat More,” in order to eat better? Source: Presented at the Experimental Biology Conference in Anaheim, CA in April 25. The forthcoming abstract will be published as: Patterson, Richard Wells, Collin R. Payne, and Brian Wansink (2011), “Tracking the Effectiveness of Various Combinations of Diet Tips: Results of the National Mindless Eating Challenge,” FASEB Journal, 2:878.7, forthcoming.

0 Comments

There’s been a lot of talk of how olive oil is healthier for a person than butter. But it seems there’s a tendency for us to put a lot more olive oil on our bread than butter.

In two different Italian restaurants we randomly gave people either olive oil or butter, and weighed the leftovers after they finished their meal. Those using olive oil ate 26% more fat calories on every piece of bread they ate compared to the more frugal butter users. Olive oil is harder to spread and it has a “health halo” which makes us feel less guilty about overindulging. Still, 26% more oil is 26% more fat. Source: Wansink, Brian and Lawrence W. Linder (2003), “Interactions Between Forms of Fat Consumption and Restaurant Bread Consumption,” International Journal of Obesity, 27:7, 866-868. All parents want their kids to eat healthy, and most of us have only one instinctual rule-of-thumb to make this happen. It involves us saying over and over something along the lines of “Clean your plate,” “Eat your vegetables,” or “Finish your chicken.”

Why do we think it’s such a good idea for our kids to belong to the Clean Plate Club? Mainly, because we think it worked for us. Most of our parents made us clean our plate, and we grew up fine. We didn’t lose our teeth; we didn’t get scurvy; we didn’t fail 1stGrade because we had too low of a broccoli-count. A year ago, I had nearly mastered the mystical Eastern art of getting my three kidsto clean their plates. I used these skills to beg, guilt, trick, scare, humor, and bribe them into finishing their food. I was convinced I would be the Gold Medal Father-of-the-Year in the Winter Olympics –this would be a new event, designed specifically around my feeding abilities. But something happened since that showed me the dark side of the Clean Plate Club. A while back I conducted a study on whether Clean Plate Club kids had better eating habits away from home. We focused on preschoolers. We figured the Clean Plate Club kids would tend to eat in a balanced, healthy way. Afterall, their responsible parents had showed them what was right, by gum. We had the parents of 63 preschoolers fill out a survey that asked them how regularly they insisted their child clean their plate. Some parents do this all the time, others are more laissez faireand basically say, “Yo, eat however much you want.” Before these 63 kids came to preschool the next day, we had rigged their school room with hidden scales embedded in the tables, and with hidden cameras that were operated by researchers with stopwatches and hand-counters. While the kids poured their Super Sugar-Cube cereal for breakfast and pawed at the dessert tray, we weighed what they poured and counted what they took. Who do you suppose took more food, the “Clean Your Plate Club” kids or the “Eat Whatever You Want” kids? We were surprised. Those in the “Clean Plate Club” –the kids whose parents insisted they finish their food at home –poured twice as much presweetened cereal (22 vs. 47 gms), and they took about 1 extra dessert than those whose parents were more laid back. In talking with these kids afterwards, here’sthe picture that emerges. When kids have no control over their food environment at home, they compensate once they leave the house. If the food’s forbidden, they pounce on it and show themselves “Who’s boss.” Within 24-hours of discovering this, I changed the way I feed my daughters. I’ve forever more traded in my “Finish your vegetables” mantra for “Have you had enough?” So did all of the other parents who are researchers in my Lab. We might not be able to control every thing our kids do at school, but we can set them up so they don’t treat it like it’s the last time they’ll ever see food. Earlier I wrote, “Most of our parents made us clean our plates, and we grew up fine.” That empty chip bag and that candy wrapper now make me wonder. Reprinted from my Family Circle Column –August 29, 2010 Mindless Eating SolutionsTM Think 20% -- More or Less.

While most Americans stop eating is when they are full, those in leaner cultures[i]stop eating when they are no longer hungry. There is probably a big calorie gap between the point where an Okinawan says, “I’m no longer hungry” and where an American says, “I’m full.” Actually the Okinawans even have a word for it. They call the concept, “hara hachi bu” – eating until you’re just 80% full. Most of us are about as accustomed with Okinawa, as we are with eating until we are no longer hungry. We are best off dishing out all the food we think we want beforewe start to eat. • Think 20% less. Dish out 20% less of whatever you think you might want to eat. You probably won’t miss it. In most of our studies, when people eat 20% less, they never realize it. If they eat 30% less, they realize it, but 20% is still under the radar screen. • For healthy foods, think 20% more. This works great for fruits and vegetables. If we cut down how much pasta we dished out by 20%, we might want to increase the veggies by 20%. [i]Our sins of dietary excess can be compared to those of French people (French Women Don’t Get Fat), tropical people (The Tropical Diet), Mediterranean people (The Mediterranean Diet), and even Okinawans (The Okinawa Diet Plan). Suppose you make a daily change in your life, like you eat one less 250 calorie candy bar or you walk one extra mile and burn up an extra 100 calories. If you do this for every day, how much less will you weigh in a year?

If you make a change, there’s an easy way to estimate how much weight you will lose in a year. You simply divide the calories by 10. That’s the number of pounds you’ll lose if you are otherwise in energy balance. One less 270 calorie candy bar each day = 27 fewer pounds in a year One less 140 calorie soft drink each day = 14 fewer pounds in a year One less 420 calorie bagel or donut each day = 42 fewer pounds in a year The same thing works with burning calories, walking one extra daily mile is 100 calories and 10 pounds a year. Exercise is good, but some think it is a lot easier to give up a candy bar than to walk 2.7 miles to a vending machine. From Mindless Eating, p. 31 The acid test for mindless eating is wolfing down a food when we know we are not hungry. How many times have we done this? Most of us could start counting as recently as today.

Over coffee, a new friend commented that he had lost 30 pounds within the past year.[i] When I asked him how, he explained he didn’t stop eating potato chips, pizza, or ice cream. He ate anything he wanted, but if he had a craving when he was not hungry he would say – out loud – “I’m not hungry but I’m going to eat this anyway.” Having to make that declaration – out loud – would often be enough to prevent him from mindlessly indulging. Other times, he would take a nibble but be much more mindful of what he was doing. Reference [i]This person, Jay S. Walker, also supplemented this with lots and lots of exercise. You know how it is. One day you are mindlessly eating ice cream in front of an open freezer door and – bam – all of a sudden you remember you have to be at the Academy Awards ceremony in three days.

How do the movie stars lose those last minute pounds before walking the runway at the Oscars? An article in People showed that what they usually do is drastic, painful – and temporary.[i] •Emma Thompson: I try not to eat sugar, and I don’t eat bread and biscuits. Actually, to be frank, I really don’t eat any of the things I love, which is unfortunate. But I will get back to ice cream soon, which is my favorite food. •Tara Reid: I won’t eat that morning and that week I will only eat protein – egg whites and chicken. It makes a big difference. You look hot for a week, but you gain it all back the next. I also drink way more water. •Vivian A. Fox: I pop herbal laxatives and drink as much coffee as I can to flush everything out. •Melissa Rivers: I limit my calorie intake and work out like crazy. I try to eat really clean the week prior. I always substitute one meal for just a salad with dressing on the side, and I dip my fork in the dressing. •Bill Murray: I did 200,000 crunches. Drastic? Yes. Successful? As you can see from their answers, these deprivation diets worked only as long as was absolutely necessary. Five minutes after the Academy Awards ceremony is over, it is back to the normal routine, and the 10 pounds that were lost begin to find their way home again. Unless you are not yet finished with your 200,000 crunches. [i]Quotations were adopted from “Last-Minute Diet Secrets, People, March 16, 2004, pp. 122-5. We have all heard of somebody’s cousin’s sister who went on a huge diet before her high school reunion, lost tons of weight, kept it off, won the lottery, and lived happily ever after. Yet we also know about 95 times as many people who started a diet and gave up in discouragement, or who started a diet, lost weight, gained more weight, and thengave up in discouragement.[i] After that, they started a different diet and repeated the same depriving, discouraging, demoralizing process. Indeed, it is estimated that over 95% of all people who lose weight on a diet, gain it back.[ii] Most diets are deprivation diets. We deprive ourselves or deny ourselves of something – carbohydrates, fat, red meat, snacks, pizza, breakfast, chocolate, and so forth. Unfortunately, deprivation diets don’t work for three reasons: 1) Our body fights against them, 2) our brain fights against them, and 3) our day-to-day environment is booby-trapped with food. Millions of years of evolution have made our body too smart to fall for our little, “I’m-only-eating-salad,” trick. Our body’s metabolism is efficient. When it has plenty of food to burn, it turns the furnace up and burns up our fat reserves faster. When it has less food to burn, it turns down the furnace and burns it more slowly and efficiently. This efficiency helped our ancestors survive famines and barren winters. It does not help today’s deprived dieter. If you eat too little, the body goes into conservation mode and makes it even tougher to burn those pounds off. This type of weight loss is not mindless. It is like pushing a boulder up hill every second of every day. How much weight loss triggers the conservation switch? It seems that we can lose half a pound a week without triggering a metabolism slow-down.[iv]Some people may be able to lose more, but everyone can lose at least half a pound a week and still be in full-burn mode. The only problem is that this is too slow for many people. Weight loss has to be all or nothing. This is why so many impatient people try to lose it all and end up losing nothing. Now for our brains. If we consciously deny ourselves something again and again, we are likely to end up craving it more and more.[v] It does not matter whether you are deprived of affection, vacation, television, or your favorite foods. Being deprived from anything you really like is not a great way to enjoy life. Nevertheless, the first thing many dieters do is cut out their comfort foods. This becomes a recipe for dieting disaster because any diet that is based on denying yourself the foods you really like is going to be really temporary. The foods we do not bite can come back to bite us. When the diet ends – either because of frustration or because of temporary success – you are back wolfing down these comfort foods with a hungry vengeance. With all that sacrificing you’ve been doing, there is a lot of catching up to do. When it comes to losing weight, we cannot rely only on our brain, or our “cognitive control,” A.K.A. willpower.[vii] We make an estimated 248[viii]food-related decisions each day, and it is almost impossible to have them all be text-book perfect. We have millions of years of evolution and instinct telling us to eat as often as we can and to eat as much as we can. Most of us simply do not have the mental fortitude to stare at a plate of warm cookies on the table and say, “I’m not going to eat a cookie, I’m not going to eat a cookie,” and then not eat the cookie. There is only so long before our “No, no, maybe, maybe” turns into a “Yes.” Our bodies fight against deprivation, and our brains fight against deprivation.[ix]And to make matters worse, our day-to-day environment is set-up to booby-trap any half-hearted effort we can muster up.There are great smells on every fast food corner. There are warm, comfort food feelings we get from television commercials. There are better-than-homemade tasting 85 cent snacks in every vending machine and gas station. We have billions of dollars worth of marketing giving us the perfect foods that our little hearts and big tummies desire. Yet before we blame those evil marketers let us look at the traps we set for ourselves. We make an extra “family-size” portion of pasta we make so no one goes hungry. We lovingly leave latch-key snacks on the table for our children (and ourselves). We use the nice, platter-size dinner plates that we can pile up with food. We heat up a piece of apple pie in the microwave while the lonely apple shivers in the crisper. Best intentions aside, we are Public Enemy #1 when it comes to booby-trapping the diets and willpower of both ourselves and our family. The good news is that the same levers that almost invisibly lead you to slowly gain weight can also be pushed in the other direction to just as invisibly lead you to slowly lose weight. This will lead us to lose weight unknowingly. If we do not realize we are eating a little less than we need, we do not feel deprived. If we do not feel deprived, we are less likely to backslide and find ourselves overeating to compensate for everything we have forgone. The key lies in the Mindless Margin. References

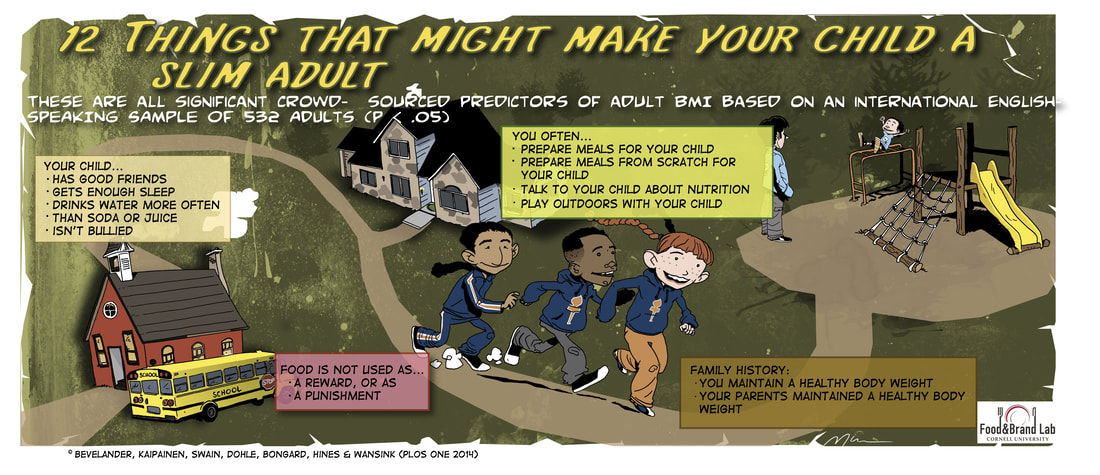

[i]The speed at which you regain weight after going off a diet is almost always directly related to the speed you lost the weight to begin with. If you miraculously lose 10 pounds in 2 days with the new Celebrity Fad Diet, you are likely to miraculously gain it back almost as fast. [ii]See Maureen T. Mcguire, Rita R. Wing, Mary L. Klem and James O. Hill, “What predicts weight regain in a group of successful weight losers?” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology(1999), 67:2, 177-185. [iii]Quotations were adopted from “Last-Minute Diet Secrets, People, March 16, 2004, pp. 122-5. [iv] This conclusion from a series of studies is alluded to in David A. Levitsky, “The Non-regulation of Food Intake in Humans: Hope for Reversing the Epidemic of Obesity,” Physiology & Behavior(December 2005), 86:5, 623-632. [v]Much of the best work of restrained eaters has been conducted by Janet Polivy and C. Peter Herman. A typical example of this is Janet Polivy, J. Coleman and C. Peter Herman, “The Effect of Deprivation on Food Cravings and Eating Behavior in Restrained and Unrestrained Eaters,”International Journal of Eating Disorders(December 2005), 38:4, 301-309. [vi]This syndicated column was widely reprinted with the name of the nationally-known psychologist. This account was taken from “News of the Weird,” Funny times, October 2005, p. 25. Lisa G. Berzins, [vii]John P. Foreyt, “Need for Lifestyle Intervention: How to Begin,” American Journal of Cardiology,(August 22, 2005), 96:4A, pp. 11-14. [viii]What is interesting is that most people initially think they only make an average of less than 30 of these decisions. It’s evidence of how mindless they are. More can be found in Brian Wansink and Colin R. Payne (2006), “Estimates of Food-related Decisions Across BMI,” under review at Psychological Reports. [ix]The best current thinking on this is being done by Roy Baumeister. See Roy F. Baumeister, “Yielding to Temptation: Self-Control Failure, Impulsive Purchasing, and Consumer Behavior,” Journal of Consumer Research(2002), 28:4, 670-76. Other work in the marketing area include that by Erica M. Okada, “Justification Effects on Consumer Choice of Hedonic and Utilitarian Goods,” Journal of Marketing Research(2005), 42:1, 43-53, and by Baba Shiv and Alexander Fedorikhin, “Heart and Mind in Conflict: The Interplay of Affect and Cognition in Consumer Decision Making,” Journal of Consumer Research(December 1999), 26, 278-92. We asked over 500 people from around the world what they believed would predict whether a child would grow up to be overweight. We then used a crowdsourcing approach to see they on target. The infographic below summarizes the key findings. Habits learned and initiated in childhood tend to be continued in adult life, and therefore a stronger focus should be placed on families as a supportive environment for establishing healthy habits. Some Methodology Details.

Participants were recruited through notices posted on reddit.com, a user-generated content news site. Notices were posted in sections focused on dieting, weight loss, and parenting. 532 individuals followed the postings and participated in the study. After entering demographic information, height and weight to calculate body mass index (BMI), and answering at least one question posed by a previous user, participants were asked to enter questions that they felt would help predict the BMIs of other participants. The questions focused on elements of one’s childhood that could predict that same individual’s BMI as an adult. The website predicted each participant’s BMI based on the growing data set. Researchers looked for questions that helped to accurately predict BMI. Of the 59 questions that were posed by the participants and seeded by the researchers, 16 questions were significantly correlated and 3 questions were marginally correlated with BMI. Elements of parenting such as packing school lunches, preparing meals with fresh ingredients, talking with children about nutrition, and engaging in regular outdoor activities were strongly related with having a lower BMI later in life. Unsurprisingly, family history of high BMI was linked to higher BMI in adults; using food as a reward or punishment and restricting food intake were also linked to higher BMI in adults. For better or worse, the nutritional gatekeeper controls around 70% of what our family eats. Children eat what tastes good and what is convenient and what portion size they see as appropriate. You can use this to help create positive lifetime food patterns.

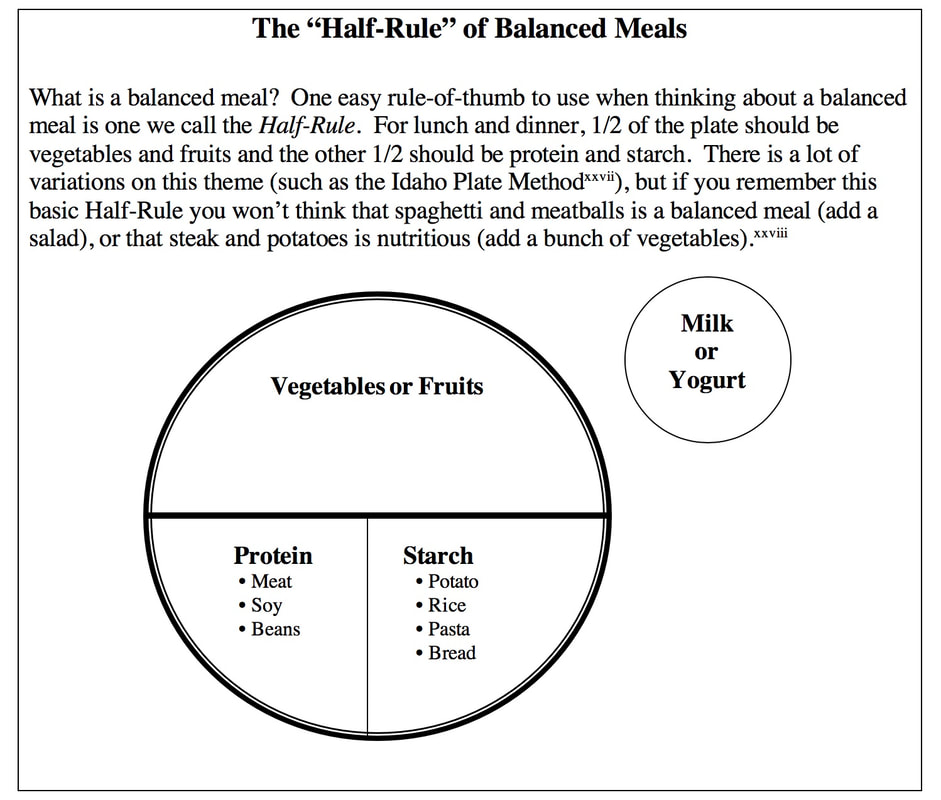

• Be a good marketer. Foods are neither a punishment nor a reward. Healthy foods can, however, be fresh, crunchy, refreshing and make make you strong, smart, and maybe even “goiter-free.” (They might even be what long-neck dinosaurs eat.) Be convincing. Some of our early findings suggest that the more foods you expose your child to, the more nutritionally well-rounded he or she may become. Marketing new recipes, new ingredients, ethnic foods, and different types of restaurants will all help mix it up and break the junk food habit. • Use the Half-Plate Rule. Around the house, the Half-Plate Rule can lead to more balanced meals, and it can give your children an idea of what is a healthy meal. Is spaghetti and meatballs a balanced meal? No, it is only half of the plate – you still need a vegetable or salad for the other half. • Make serving sizes official. Provide “official” servings by giving them their snacks in sealed baggies, in Tupperware, or in Saran Wrap. Do not let them see extra snacks. We found that any extra snacks on the counter increase the amount they see as a serving size. Clean the counter at snack time. The serving-size habits we adapt as children can continue to influence us through our whole lives. This fat-forming transformation in our eating habits happens between the ages of three and five. You can give a three-year-old a lot of food and they will simply eat until they are no longer hungry. They are unaffected by serving size. By age five, however, they will pretty much eat whatever they are given. If they are given a lot, they will eat a lot, and it will even influence their bite-size. This has been vividly shown by LeAnn Birch at Penn State and Jennifer Fisher at the Baylor Medical School.[i] When they gave three- or five-year-old children either medium-size or large-size servings of macaroni and cheese, the three-year-olds ate the same amount regardless of what size they were given. They ate until they were full, and then they stopped. The five-year-olds, rose to the occasion and ate 26% more when given the bigger servings. This is almost the exact same thing that happens to adults. We let the size of a serving influence how much we eat. Serving size is a problem at meal time, but it is also a big problem at snack time. What is a healthy-sized snack? Children tend to think that a serving size is open-ended and up for negotiation – it is pretty much whatever food is available and whatever they can weasel out of their parents. If a candy bar comes in a two ounce package, two ounces must be the correct serving. If the candy bar comes in a four ounce package, four ounces must be the correct serving. How do we adjust serving size to be more reasonable and less negotiable? One tricky way is to influence how much children believe is still available to eat. If they believe plenty of the snack is available, the serving size is whatever they can argue for, cry for, and negotiate. Suppose you make a peanut butter and jelly sandwich as a snack and give them half of it. Is the serving-size half the sandwich? Not if the other half of the sandwich is still sitting on the counter. At that point, a serving includes anything that is left that can be eaten. What happens if you bought raisins in bulk and gave them a quarter cup of them. The same thing. A quarter of a cup is not a serving – a serving can expand to include is whatever’s left that they want to eat. If you buy in bulk to save money, you can use the baggy trick. Remember that none of us really seem to know the amount of a “correct” serving size. We typically look at whatever is wrapped or served and we assume that must be one serving. We can use this notion with our children by giving them their snacks not on a plate, but by putting them in a baggie (or even in a small Tupperware container). In this way, when children get it, they believe it is all they are going to get. There is no more, because this was what was in the container. As long as the extras are out of sight, one serving is whatever they were given. Children look at cues to determine whether they want more to eat. If they think more is available, they can easily think they are still hungry. For instance, in one of our pilot studies, we gave five-year-olds at a day care center six mini-sized cookies in either a zip-lock baggie or on a plate. After they finished the snacks, we asked them if they thought there were any more cookies. Those children who were given cookies on the plate believed that there were more cookies left in the kitchen and they indicated they wanted them. Those children getting the cookies in the baggies were more likely to believe that the cookies were all gone and that snacktime was over. References

[i]Many of these classic studies were conducted at the Child Behavior Labs, when both were at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. LeAnn L. Birch and Jennifer O. Fisher, “Mother's Child-Feeding Practices Influence Daughters' Eating and Weight,” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, (2000), 71, 1054-61. LeAnn L. Birch, Linda McPhee, B. C. Shoba, Lois Steinberg, and Ruth. Krehbiel, “Clean up Your Plate: Effects of Child Feeding Practices on the Conditioning of Meal Size,” Learning and Motivation, (1987), 18, 301-317. See also Barbara J. Rolls, Dianne Engell, and LeAnn L. Birch, “Serving Portion Size Influences 5-Year-Old but Not 3-Year-Old Children's Food Intakes,” (2000), 100, 232-234. Jennifer O. Fisher, Barbara J. Rolls and LeAnne L. Birch, “Children’s Bite Size and Intake of an Entrée are Greater with Large Portions Than with Age-Appropriate or Self-Selected Portions,” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition(2003), 77, 1164-1170. The word “conditioning” conjures up images of food, ringing bells, and Pavolv’s dogs. In the turn-of-the-century pre-Bolshevik Russia, Ivan Pavolv rang a bell and fed dogs frequently enough for them to associate the ringing of the bell with food. Eventually the dogs started to salivate every time they heard the bell – even if there was no food. Eighty years later, psychologist Leann Birch reran this study with a few twists. She and her team repeatedly gave preschool children snacks in a specific location where they would always see a rotating light and hear a certain song. They came to associate the light and the song with snack-time and eating. On a different day shortly after they had finished lunch, she turned on the light and played the song again. Dog-gone it – they started eating again.[i] When we condition our children, we do not do so with lights and music, but with our words and behavior. Take the Popeye Project.[ii]My Lab is trying to understand why some children curiously develop powerfully positive associations with healthy foods – such as broiled fish, broccoli, and even seaweed – that are not typically liked by most children. In beginning this work, we conducted separate interviews with children and with their parents. These interviews took an abrupt right turn a couple weeks after they began. We expected that the children with positive associations toward healthy foods “inherited” them from their parents. While true in some cases, in other cases, the parents did not leave this to chance. These parents explicitly associated the foods with a positive benefit – such as “spinach makes you strong like Popeye.” Some children grew up eating a lot of fish because their parents told them it would make them smart. Others were told to eat lots of carrots so they could see far distances, meat so they would be strong, bananas so they would have strong bones, and fruit so they could keep cool in the summer. A couple children (whose parents were originally from China) even grew up eating – and loving seaweed – because they were told it would prevent “stomach disease” and goiters.[iii] Hard to see that one as a big motivator to a four-year-old. That first day of school would be one to remember, “Hi, I’m Jennifer. What I did on my summer vacation was to go to the beach and eat seaweed so I can be goiter-free.” We’ve interviewed dozens of 3-5 year olds through the Popeye Project so far, and we have collected a lot of insights related to healthy eating. Yet an odd set of interviews occurred in early 2006. At one particular daycare center in Ithaca, NY, a number of the children had uncharacteristically strong preferences for broccoli. This seemed unusual because this bitter vegetable is not as kid-friendly as others (such as carrots and peas). Many of the children loved broccoli because their friends liked it and because it was cool. Most of these associations we could trace back to two brothers. In their laddering interviews both said it reminded them of dinosaur trees, and they liked it because of that. This did not make much sense but because of the far reaching impact it seemed to have on the rest of the daycare we decided to interview their parents. We discovered their mother had convinced them that when they ate broccoli, they could pretend they were “long-neck dinosaurs eating the dinosaur trees.” At the dinosaur-loving age of 2 and 4, that was pretty cool, and it quickly became pretty cool to their friends. Brainwashing, conditioning, or just a smart parent? Viva la Brontosaurus. My Lab tried to leverage this with a vacation Bible School group a short time ago. The children could choose what they wanted from a lunch buffet, but each day we would rename foods to give them better associations. For instance when we renamed peas to “Power Peas,” the number children taking them would nearly double. The most embarrassing poetic license we took was with a V-8-like vegetable juice. We ran out of stock on the days we renamed it “Rainforest Smoothie.” These associations are not wrong although they might be a little stretched – Einstein probably did not make his breakthroughs while eating “brainfood” whitefish at Long John Silvers or the Red Lobster. Nevertheless, just as negative food associations of reward, punishment, comfort, or guilt follow children to adulthood, so can the positive associations of what good food can do for them.[v] But words also work the other way around. Negative associations can be made with unhealthy foods. While we have all heard, “If you eat that, you’ll get fat,” that is not a strong or very vivid form of conditioning. While there are not too many published studies on this, it is an area rich with anecdotes. Joyce is an interesting example. As an adult, she never had cravings for cake and cookies. For 45 years, she has never had to fight the gravitational pull that these sweet snacks have on most of us. Why no apparent sweet tooth? It is almost a Manchurian Candidate brainwashing explanation. As a little girl, her mother repeatedly told her that eating sweet snacks between meals was what low class people did.[vi]Extreme, yes. Bourgeois, yes. Politically incorrect, yes. Yet because there were no sweet snacks available and because she had a (unmerited) stigma attached to them, Joyce never developed the temptation toward these foods that has cursed most of the rest of us. It is not just food availability that drives kiddy consumption, it is also the food conditioning and reinforcement routine set by Mom and Dad. The 4 Ps of Feeding the Finicky An expert who specialized in feeding finicky eaters told me about the 4Ps of feeding the finicky. Positive: Make mealtime a positive experience and praise your kids. Patience: Don’t take food rejection personally Persistence: Keep trying; it might take 15 tastes before tastes begin to change Physical activity: The more they move, the hungrier they will be at mealtime References

[i]We use this book in the field when making child-friendly foods for our studies: Sheila Ellison and Judith Gray,365 Foods Kids Love to Eat: Fun, Nutritious, Kid-Tested and Kid-Approved(New York: Gramercy Books, 1995. [ii]This new area of study is focusing on how why some children develop positive views toward healthy foods, while others do not. The foundation for this is based on what we learned about how comfort foods are formed with adults which is found in Brian Wansink and Cynthia Sangerman, “Engineering Comfort Foods,” American Demographics(July 2000), 66-67. [iii]Both of these children, whose parents were originally from mainland China, were raised almost exlusively on Chinese food. Although iodized salt supposedly supposed to prevent a thyroid condition, this knowledge certainly would not encourage increased seaweed consumption. [iv]This little nugget was from Carolyn Wyman’s very entertaining book, Better than Homemade, (2004, Philadelphia: Quirk Books). [v]Paul Rozin, Nicole Kurzer, and Adam B. Cohen, “Free Associations to “Food”: The Effects of Gender, Generation, and Culture,” Journal of Research in Personality(October 2002), 36:5, 419-441. [vi]This is a common perception in France with snacking. Among the Bourgeois snacking between meals is still considered a behavior well-mannered people do not do. Here's the short answer: The answer partly depends on the parents. A study of 854 Washington state children under 3 years old showed that a child is nearly three times likely to grow up obese if one of his parents are obese. If you are overweight, your child has a 65-75% chance of growing up to be overweight.[i] So, is that little paunch on your 4th grader baby fat? Not if you are sporting the same paunch. ----- References Excerpted from the American Dietetic Association’s excellent book, Dieting for Dummies (Wiley, 2004). Bevelander, Kirsten E., Kirsikka Kaipainen, Robert Swain, Simone Dohle, Josh C. Bongard,Paul D. H. Hines, and Brian Wansink (2014), “Crowdsourcing Novel Childhood Predictors of Adult Obesity,” PLOS ONE, 9:2, e87756.  We decided to see if we could track down the mysterious North American Good Cook and get some psychographic snapshots of them and the impact they have. To do this, we surveyed 453 “good cooks” who were considered “way above average” by at least one member of their family. They came from a wide range of ethnicities, income levels, and education levels. Besides being good cooks, the all had one thing in common – they had never attended culinary school. Some learned from a parent or on their own, some cooked out of necessity, and some for fun. We asked them 152 questions about how they cooked, what they cooked, when they cooked, what kind or person they were, what they did in their spare time. Almost everything. We found that although not all good cooks are created equal, 82% of them fit fairly neatly into one of five personality profiles. They could either be classified as Giving Cooks, Competitive Cooks, Healthy Cooks, Methodical Cooks, or Innovative Cooks. All of these cooks – except one – appeared to help their family eat healthier. They all did this largely through the variety of food they served. Serving a wide variety of food can make eating pleasurable and can lead their children and spouse to enjoy a wide range of foods other than the standard, fatty, salty, sweet ones for which we have a natural hankering. Which great cook seemed to have the least positive impact on adult eating habits? Interestingly enough, it was the most common one – the Giving Cook – and they were also the most frequent baker and dessert maker. Although they still put the stamp of variety on their meals, it was in the form of carbohydrates instead of the form of vegetable-heavy cuisine. Does this mean that if you are not a good cook that your children are destined to grow up eating dinners that consist of Dominos Pizza and Cheetos? No, of course not. What it reinforces is that parents can influence the eating habits of their children in either a good way or a bad way. One key take-away for us “not so good cooks” is the good we cando just by adding more variety to our meals. How? These good cooks do it by 1) buying different foods, 2) making different recipes (including different ethnic foods), 3) substituting new ingredients into favorite recipes (mainly vegetables and spices), 4) taking kids to the grocery store and letting them choose a new, healthy food, 5) visit authentic ethnic restaurants. Relevant to the last point, McDonald’s is not a Scottish restaurant. When a child develops a taste for a wide range of foods, healthy foods can be more easily substituted for the less healthy ones. The more he or she will develop a taste for something other than pizza, French fries, candy, and Juicy-Juice. They still may not learn to lovebroccoli, but they will be more willing to eat it occasionally for dinner or with a low calorie ranch dressing as a snack.[i] ---- Picky eater at home? Take heart. Gentle persistence will be rewarded. One taste does not change a person. Professor LeAnn Birch suggests that this can take up to 15 one-bite attempts, but most children end up eventually coming around to liking more than just French fries, ice cream, and Jell-o. Lessons from the Great Cook Next Door All cooks influence their families more than they realize, but great cooks seem to be able to turn children into healthier eaters. What is a great cook look like? A study of 453 great cooks, showed that most of them tend to fall into one of five basic groups:[i] • Giving Cooks (22%). Friendly, well-liked, enthusiastic cooks who specialize on comfort foods for family gatherings and large parties. Giving cooks seldom experiment with new dishes, instead relying on traditional favorites. The only fault of the Giving Cook is they also tend to provide too many home-baked goodies for their family. • Healthy Cooks (20%). Optimistic, book-loving, nature enthusiasts who are most likely to experiment with fish and with fresh ingredients, including herbs. • Innovative Cooks (19%). The most creative, trend-setting of all cooks. They seldom us recipes, they experiment with ingredients, cuisine styles, and cooking methods. • Methodical Cooks (18%).Often weekend hobbyists who are talented, but who rely heavily on recipes. Although somewhat inefficient in the kitchen, their creations always look exactly like the picture in the cookbook. • Competitive Cooks (13%). The Iron Chef of the neighborhood. Competitive cooks are dominant personalities who cook in order to impress others. These are perfectionists who are intense in both their cooking and entertaining. Do not fit into one of these categories? No worries. Find the cooking personality that best resembles you or that you most aspire to be. Then simply try to cook at home. The key is in your habits – your shopping habits, cooking habits, and eating habits. Learn that they do not sell toast in the grocery store. Learn the recipe for boiled water. Then simply give your children a wide varied diet and reasonable serving sizes. The food does not have to be great – just varied and reasonably sized.

[i] See Brian Wansink, “Profiling Nutritional Gatekeepers: Three Methods for Differentiating Influential Cooks,” Food Quality and Preference(June 2003), 14:4, 289-297. In most households, the decision of what to eat for breakfast, lunch, dinner, and snacks is determined by what foods the grocery shopper – the nutrition gatekeeper – purchases. Suppose a teenager wants to eat Pop-tarts, but there are not any in the house. The gatekeeper has de facto decided they won’t be on the menu. This poor Pop-tart hungry kid would have to make a special trip to the grocery store, or start a campaign to put them at the top of the next shopping list. The convenience rule suggests that most of them won’t bother.

On a steamy Manilla-like August day in Washington DC, I met with 800 dieticians and nurses at the American Associations of Diabetes Educators. These people are paid to know how people shouldeat and how they doeat. They deal with the power of dietary influences day in and day out. I asked them about the Nutritional Gatekeeper, the person who does most the shopping and cooking in a household (92% of the time this is the same person). I asked them to estimate what percentage of the food eaten by their family – snacks, meals, out-of-the-house meals, everything – did they control. Their answers surprised me. They estimated that the Gatekeeper controlled an average of 71% of the food decisions of their children and spouse.[i] Not only did they buy everything that was eaten at home, they also made their children’s lunches or gave them enough money to afford whatever lunch or snack they wanted. They even nudged the family restaurant orders by what they recommended or ordered themselves. We have asked over 2000 to estimate this percentage. Some are 10 points lower or 10 points higher, but its always in this range. One group, however, stood out because their estimates were so high. These were people who also rated themselves as good cooks. This makes some sense. It is in line with a study we did that showed that many veggie lovers[ii]claimed to either be a good cook, live with a good cook, or to have had a parent who was a good cook.[iii] [i]Whereas the dieticians estimate 72%, people in the general population generally range from 60-70%. It is a high number. For the details see Wansink, Brian and Collin R. Payne 2006, “Mindless Eating and Estimations: Reported Food Decisions in the Household,” under review Psychological Reports. |

The Mission:For 30 years my Lab and I have focused on discovering secret answers to help people live better lives. Some of these relate to health and happiness (and often to food). Please share whatever you find useful.

Blog Categories

All

|

||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed