|

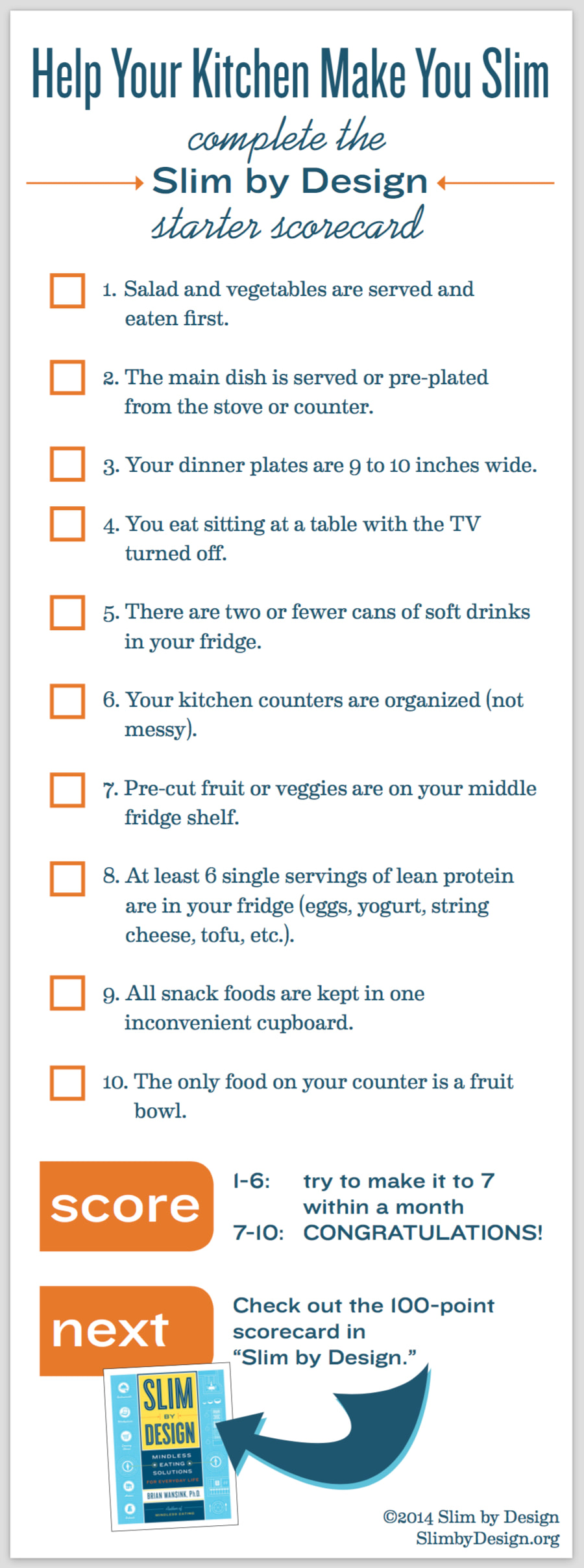

You almost have to be a Super Hero to make more than 3 changes in your life at any one time. Over the years many people have asked me how they could eat better, snack less, avoid eating seconds at dinner time, not binge so much at receptions, lose their sweet tooth and so forth. One thing I discovered is that even if a person is given perfectly stylized, guaranteed solutions, even the most dedicated person has problems making over 3 changes in their life at one time. That is why the Power of Three works. The Power of Three is finding three small changes you think would be helpful and easy for you to make to eat better. The important thing to do is to focus at defusing your diet danger zone, whether it be dinners, snacks, parties, restaurants, or work. All you need to do is to choose no more than three small (100 calorie or so) changes in your daily food routine that you would like to make. Why only three? Most diets fail because they ask us to do too much. Three small changes is more reasonable. If we make these three small changes, by the end of the year we will be as much as 30 pounds lighter than we would be if we did not make them. You start by first identifying your Dietary Danger Zone. There are five Dietary Danger Zones that trip up most people (meal stuffing, snack grazing, desktop/dashboard dining, party binging, etc.). Most of us are guilty of all of them. However, at this specific moment, there is one of them that is most troublesome in your life. The divide and conquer idea here is to only focus on this one specific area this month. Next, you choose three small changes you could make in that one area for 30 days. After that point, you tackle the next Dietary Danger Zone that is most problematic for you. It might be the same one or it might be a different one. You find three small changes to make, you keep them for a month, and after a month you can either stop doing them, or continue. For instance, say that you suspect that meal stuffing is the biggest problem you have. Simply decide on 3 little changes you could make at meal time that you think could help you eat just a little big less. That is, changes that might help you serve less, or help you not go back for seconds, or eat a little better. For instance, you might say to yourself that you're going to use smaller (9 to 11-in) plates, pre-plate your food before sitting down at the table, and use the Half-Plate Rule. You do each of these each night for dinner for a month. After a month, you go to the next most troublesome Dietary Danger Zone. You don't have to do any one thing for more than a 30 days unless you want to. If you've decided which Dietary Danger Zone you want to tackle this month, you'll find lots of ideas on this website. Here's starting points for your home, your workplace, when you're shopping, and eating out. If you need more, Mindless Eating and Slim by Design have even lots and lots more. You might want to start your first month off by taking three daily changes off of our 10-point Kitchen Scorecard below. It does not matter what changes you choose, just do not get over ambitious and choose more than three. The more you try to tackle right away, the more difficult it will be to keep track of them. The whole key is to keep this mindless. Good luck. I look forward to hearing how it goes.

1 Comment

If your New Year resolutions to eat better didn't work out as planned. Here's Plan B. Trick yourself into eating better. You can easily set up your kitchen (and some habits) that lead to eat better or less. But since you will know what’s going on, you won’t have to feel tricked. A while back "Trick Yourself into Eating Better was the title Quartz used for a catchy story on some of our research. It’s about 3 minutes long and has a lot of eye-opening tips and insights. They interviewed one of my post-doctoral fellows, Aner Tal. What’s unusual is how Aner describes why these work in a suave James Bond style and how Quartz cleverly illustrates them. Too cool for school. Here’s some of what they mentioned:

1. Use lighter plates 2. Use smaller plates 3. Cut your food into pieces 4. Don’t watch TV when you eat 5. No scary movies 6. Don’t shop when you’re hungry (you don't buy more, you buy worse) 7. Deprivation always backfires Some of these might sound pretty basic, but it’s Aner's description of how they work and Quartz's funny illustrations that really make them pop. Aner flew out to visit me from Israel a while back, and we were talking about how people react after they hear about some of these discoveries. Some people hear about suggestions like these and say to themselves “That would never happen to me,” so they don’t try to do anything different, and nothing changes in their life. Other people say to themselves, “Yeah, that makes sense” but they never do it, so, again, nothing changes in their life. No one is going to hear about 7 discoveries and make 7 changes in their life. It’s too much. But you can make 1 or 2 of them. After they become habits, you can always come back to the table for another course. |

Welcome!Here are some tips, tricks, and secrets on how you and your family can eat to be healthier and happier. They're based on over 30 years of our published research.

Fun InterviewsMost Visited Last Month• For You

• Smarter Lunchrooms • The X'Plozionz Band • Help your family • Kitchen Scorecard • Retracted papers • Grocery secrets • Do kids inherit taste? • Be healthier at work • How not to retire • Estimating calories • Restaurant Secrets • Syllabus template Top 2024 Downloads• Kitchen Makeover

• Smarter Lunchrooms • Smarter Lunchroom Scorecard • Grocery Shopping Hacks • Restaurant Secrets • Write a Useful Syllabus • Workplace Wellness Tips • Healthy Profitable Menus Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed