|

Here’s some of what they mentioned:

1. Use lighter plates 2. Use smaller plates 3. Cut your food into pieces 4. Don’t watch TV when you eat 5. No scary movies 6. Don’t shop when you’re hungry (you don't buy more, you buy worse) 7. Deprivation always backfires Some of these might sound pretty basic, but it’s Aner's description of how they work and Quartz's funny illustrations that really make them pop. Aner flew out to visit me from Israel a while back, and we were talking about how people react after they hear about some of these discoveries. Some people hear about suggestions like these and say to themselves “That would never happen to me,” so they don’t try to do anything different, and nothing changes in their life. Other people say to themselves, “Yeah, that makes sense” but they never do it, so, again, nothing changes in their life. No one is going to hear about 7 discoveries and make 7 changes in their life. It’s too much. But you can make 1 or 2 of them. After they become habits, you can always come back to the table for another course.

0 Comments

Eating a balanced diet used to be easy when you were little. Your grandmother put a variety of things on the table, you’d eat a little of each, and – ta-da – that was nutrition! Since then, eating’s gotten strangely complicated, with the Atkins diet, flexitarian diets, paleolithic diets, velociraptor diets, and so on. Each one makes a magical case for why we should only eat meat, or never eat meat, or eat only vegetables, or eat only bananas or grapefruits or cabbage and so on. It makes it harder to eat nutritiously than it was when your grandmother said, “Make sure you take a little of everything.”

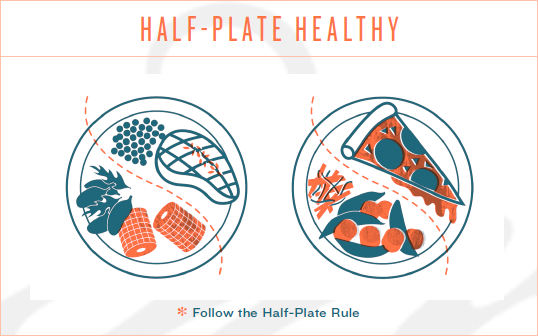

In June we published interesting study in the medical journal Cureus that shows there might be an easier way for people to eat called the Half-Plate Rule. Half of their plate had to be fruit, vegetables, or salad, if so, the other half of their plate could be anything they wanted. Steak, bread, pasta, foie gras, Pop Tarts . . . anything. They could also take as many plates of food as they wanted. It’s just that every time they go back for seconds or thirds, half their plate still had to be filled with fruit, vegetables, or salad. Could a person load up half of their plate with Slim Jims and bacon? Sure, but they don’t. Giving people freedom – a license to eat with only one guideline – seems to keep them in check. There’s nothing to rebel against, resist, or work around. As a result, they don’t even try. They also don’t seem to overeat. They want to eat more pasta and meatballs or another piece of pizza, but if they also have to balance this with a half-plate of fruit, vegetables, or salad, many decide they don’t want it bad enough. Nobody likes be told they can’t do something. With the Half-Plate Rule there’s nothing you can’t eat. You just have to eat an equal amount of fruit, vegetables, or salad. At some point, getting that fourth piece of pizza just isn’t worth having to eat another half-plate of salad. But, most important, you’re the one who made the decision. Interestingly, what we found was that although it's easy to understand the Half-Plate Rule, it's not alway easy to follow if the only thing on the table is pizza or take-out food. There have to be fruits, vegetables, and salad in the house before you can eat them. All my best in half-plate happiness and health. |

Welcome!Here are some tips, tricks, and secrets on how you and your family can eat to be healthier and happier. They're based on over 30 years of our published research.

Fun InterviewsMost Visited Last Month• For You

• Smarter Lunchrooms • The X'Plozionz Band • Help your family • Kitchen Scorecard • Retracted papers • Grocery secrets • Do kids inherit taste? • Be healthier at work • How not to retire • Estimating calories • Restaurant Secrets • Syllabus template Top 2024 Downloads• Kitchen Makeover

• Smarter Lunchrooms • Smarter Lunchroom Scorecard • Grocery Shopping Hacks • Restaurant Secrets • Write a Useful Syllabus • Workplace Wellness Tips • Healthy Profitable Menus Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed